Argentina’s New Immigration Policy

New immigration regime by presidential decree: an overview of changes and next steps

Welcome Avatar! It looks like the good old days of visa runs in Argentina or staying indefinitely without going through a residency procedure are officially over. The Milei administration is tightening the noose on all illegal immigration, for Mercosur nationals and passport bros alike.

In a statement this week, presidential spokesman Manuel Adorni announced setting stricter requirements for citizenship and residency in the country:

“Argentina has had an immigration policy that invites chaos and abuse for many people who are far from coming to this country honestly to build a prosperous future. Today, almost anyone enters, without much question, and deportation conditions are overly lax.

In the last 20 years, 1,700,000 illegal immigrants have entered the country, equivalent to the population of, for example, La Matanza district or the province of Tucumán.

Furthermore, Argentina was overly permissive with those who entered legally. Today, anyone convicted of serving less than three years can enter Argentina. There are also immigrants who come to the country to use free public services that they don't have in their countries and who didn't contribute their taxes to fund them. In the case of the famous health tours, for example, they come to the country, receive care in a public hospital, and immediately return to their place of origin.”

According to the government, the modification of the Immigration Regime through a Decree of Necessity and Urgency (DNU) has “the aim of restoring order, security, and equity in access to Argentine state resources.” Adorni confirmed this in his press statement by underlining the new rules around migrants who were convicted of a crime:

“What's worse, today Argentina doesn't expel those who break the law either. Under current regulations, any immigrant convicted of a crime with a sentence of less than five years can continue to live happily in Argentina, much to the danger of everyone else. […]

From now on, any convicted person attempting to enter across the border will be rejected by immigration authorities. And those caught in the act of entering through unauthorized crossings will be immediately expelled.

Anyone who lies in any information that may lead to their entry will also be expelled. Argentina will not be fertile ground for the arrival of criminals. Furthermore, anyone convicted of committing a crime will be deported, regardless of the crime, and the appeals process for expulsions, which currently seem endless, will be reduced.”

In practice, no border agent will ask for a criminal record but during residency procedures one of the requirements is a copy of your criminal record.

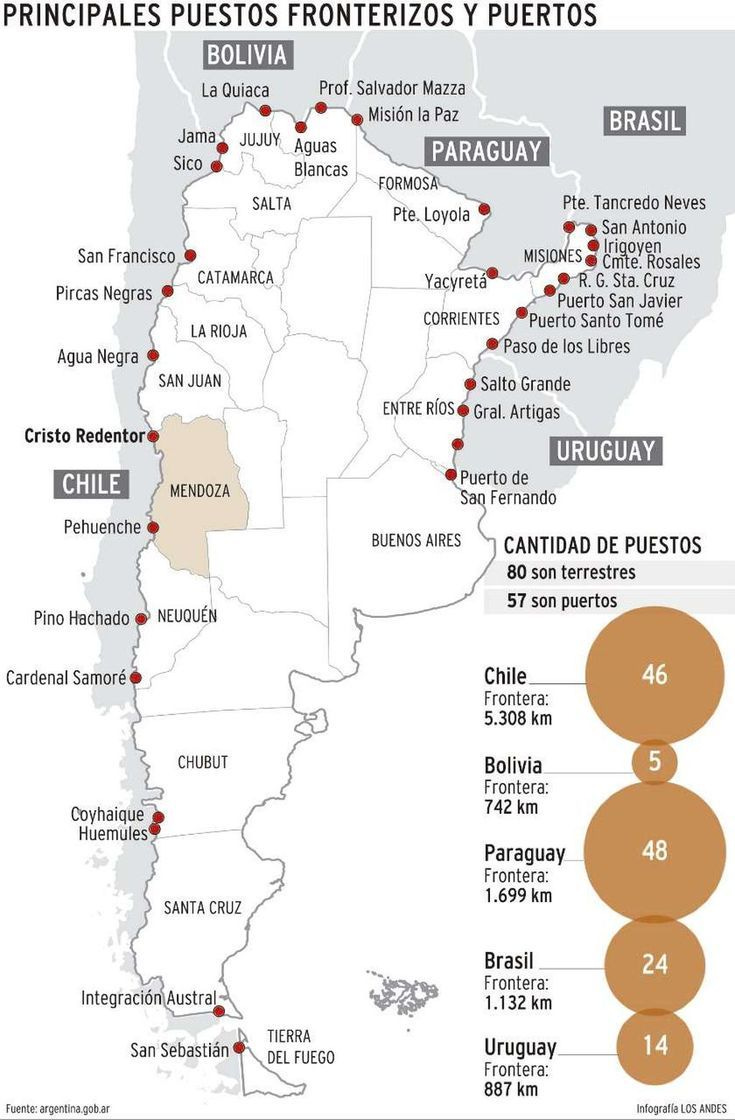

The part about unauthorized crossings is an interesting one, since many land and river crossings to and from Paraguay and Brazil do not require a passport stamp when using urban transportation — for example when using an urban city bus between Foz do Iguaçú (Brazil) and Puerto Iguazú (Argentina).

In Brazil when leaving the country through an airport, not having the entry stamp would be an issue and meant a fine and some police questioning on next entry — happened to me once, I had simply lost the little paper you receive on entry —, and it seems that from now on the same will apply for Argentina.

Argentina’s biggest migratory problem, as Adorni also confirmed, has always been freeloaders using the public healthcare or education system (up to University bachelor’s degrees are “free” in Argentina) without ever having contributed a peso in taxes:

“There are many good immigrants who come and remain in our country under the law, who come to work, to build their future. It is not fair to them that we allow those who do not comply with the same rules to remain in our territory outside the law.

From now on, illegal immigrants, transient and temporary residents, will have to pay for health services.

And those who enter Argentina will have to present health insurance to guarantee their ability to pay. National universities will also be authorized to charge for their services, if they so wish, respecting university autonomy. I repeat once again, if they so wish.”

Public universities in Argentina are autonomous organizations, so the national government cannot force them to charge tuition for undergrad studies, which is why Adorni stressed that last part in order to avoid media backlash.

In practice, this will come down to the same as it is now: public universities will not charge for Bachelor degrees, and only for Master’s and up.

For the healthcare sector the change is more significant, especially given the fact that this new rule will also apply to “transient” (read: tourists) and “temporary residents”, which is the 2 year (Mercosur citizens) or 3 year (Other nationalities) period before obtaining permanent residency. Before, all of these groups including illegal immigrants would be attended without charge at public healthcare institutions. Last year, 114 billion pesos (little under $100 million USD) was spent on treating foreigners in just eight national hospitals.

One of the biggest changes Adorni announced was related to permanent residency and citizenship rules:

“[…] the requirements for obtaining permanent residency and Argentine citizenship will also be stricter.

Argentine citizenship will only be granted to those who reside continuously in the country for two years, without leaving the country.

Those who enter or remain illegally will no longer be rewarded with citizenship, as has been the case until now.”

It was always an insane scenario that Argentina actually granted citizenship to “inhabitants” no matter what their migratory status — even illegals could make a case with a lawyer that they should be granted citizenship under the Constitution without ever having regularized their residency status — so that change seems reasonable.

The first part about residing continuously in Argentina for two years without leaving the country in order to apply for citizenship is less logical. It does seem a bit crazy that if you want to apply for citizenship that you wouldn’t even be able to go to the beach in Brazil for two weeks or to visit your family abroad, but that is literally what Adorni is saying. I am eagerly waiting for the final text of the decree, which should be issued any day now.

If you are currently technically illegal in Argentina (for example by overstaying on a tourist visa), I recommend starting the residency process sooner rather than later.

Apply directly with my recommended immigration attorney to start your residency process in Argentina here:

In the rest of this article we will go over other motivators for these changes, the upcoming debate in Congress, and how to best plan Argentina as a plan B if you haven’t started your residency process yet. One key change has to do with maintaining permanent residency, which will also change and will be covered below.

I will also go over the best healthcare options for those on a temporary residency visa in Argentina at the moment.