YPF: the laundromat of the century

How a handful of politicians pulled off an impressive loophole that netted them billions

Welcome Avatar! Argentina is in a league of its own in many items, and today we will go over one of the biggest financial frauds in terms of money laundering, that could potentially top Brazil’s Lava Jato (Operation Carwash).

We will see how YPF, the national oil company, switched from public to private and back, with one untouched shareholder raking in billions before, during and after this process, all without investing a dime of its own money.

The 2012 YPF Expropriation

On April 16, 2012, the then President of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, presented a bill for the Argentine State to expropriate part of the Spanish company Repsol's shares in YPF, declaring 51% of YPF's assets of public utility and subject to to expropriation.

Of that 51% expropriated, 49% would go to the provinces and the remaining 51% to the National State.

The president justified this decision because she considered that the company maintained insufficient investment and little production.

As we will see in this article, there is more than meets the eye, and as is often the case, most expropriations are not distributed equally.

A year later in 2013, Repsol renounced any type of claim, when the Repsol Board of Directors approved the compensation agreement for the nationalization of 51% of YPF's shares, by which Argentina guaranteed the payment of 3,7 billion euros and the resignation of future claims.

But Repsol wasn’t the only party in this racket. Grupo Petersen just entered the chat.

First flip - the 1990s YPF privatization

First we have to backtrack a bit to 1990s, to explore the initial privatization of YPF, while Néstor Kirchner was governor of the Santa Cruz province (he would later become President in 2003, and his wife Cristina would follow his footsteps with 2 mandates, from 2007-2015).

1992: Santa Cruz YPF Royalties

In 1992, through an agreement signed between the Nation and the hydrocarbon-producing provinces, the Government of Carlos Menem recognized the sum of US$ 630,100,000 between cash and titles (adjusted for inflation this would be $1.35B) in the concept of YPF's ill-liquidated oil royalties, in favor of the province of Santa Cruz.

The money was first deposited in a New York bank, and then ended up in a Credit Suisse bank (funny in hindsight — these guys are always involved), in Switzerland.

As Néstor Kirchner explained in an interview (see image below), he made the decision as governor of Santa Cruz due to a lack of confidence "in the country's leaders." 1

With part of the money, governor Néstor Kirchner bought 5% of YPF shares at US$19 a share. Six years later, in 1999, when the second stage of the final privatization of YPF was completed, Kirchner sold those shares to Repsol for $44 each. A pretty decent trade.

However, from that 630 million US token that the district of Patagonia had received at the time, in 2020 only a little more than $9,000 remained deposited, and no one knows what exactly happened to the rest of the funds.

Keep this 630 million dollars in mind, they will resurface later in this story.

1999: Repsol Privatization of YPF Secured

With those final shares of Santa Cruz, and those of the other oil provinces and the Argentine State and those that were listed on the Stock Exchange, Repsol had concluded the privatization of YPF in 1999 with 99% of YPF privatized, and no more state owned shares.

Ezkenazi and Grupo Petersen

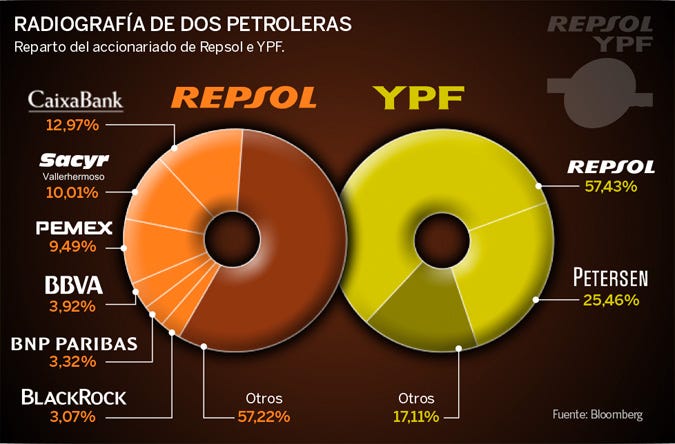

See that graph up there with the share division for YPF at the time of the privatization? Let’s dive into that 25.46% now, and Grupo Petersen’s role in this wild tale.

Enrique Esquenazi, born in 1925, buys construction company Grupo Petersen in 1980. In the 1990s, he took advantage of his friendship with the Interior Minister under Carlos Menem, Carlos Corach, to win the privatization of the banks of Entre Ríos, Santa Fe, San Juan and Santa Cruz (1998), where he got acquainted with governor Néstor Kirchner, and they became good friends.

After winning the bid for the majority of the Santa Cruz bank shares, Grupo Petersen effectively administered, among other funds, the 630 million dollars that the province of Santa Cruz transferred abroad by Kirchner's decision.

Now how did Grupo Petersen end up with 25%+ of the YPF shares?

To buy 25% of YPF, Grupo Petersen took loans from the company who sold them the shares, Repsol, for US$ 1.685 billion, together with loans from international banks (Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs and Citi, BNP Paribas, Itaú, Standard and Santander) for $1.688 billion.

They did so through two Spanish companies: Petersen Energía SA (PESA) and Petersen Energía Inversora SA (Peisa). The loan payments were tied to the distribution of future YPF dividends, lol.

Grupo Petersen put up $110 million through an Australian company called Petersen Energy Pty Ltd, which received another $71.5 million loan from Credit Suisse. This Swiss bank was the same one where Santa Cruz deposited the YPF royalty funds we saw above, and these funds were also managed by… Grupo Petersen, through the Santa Cruz bank.

It is striking that Grupo Petersen could finance an operation for more than a billion dollars of credit without knowing how these loans were guaranteed. Doesn’t take a genius to figure out what kind of circle jerking was going on here.

The agreement was sealed in 2008, when the Petersen Group bought 15% of the shares; in 2011 it would get another 10%.

Grupo Petersen bought 25%+ of YPF’s shares, paying 55% directly through these loans which backing it was indirectly managing through the Santa Cruz Bank, the and the remaining 45% with a loan from Repsol itself, which was guaranteed by the shares of YPF itself, a loan which would be paid back by future dividends.

So without assets, Petersen acquired several billion dollars of YPF shares through shell companies with financing based almost entirely on future dividends. It is not every day that practically free FU money stares you in the face like that, anon.

The gutting of YPF

It is not surprising that with the 25%+ free airdrop, Repsol and Grupo Petersen started to take out more money than YPF was making.

The four members of the Petersen group who integrated the leadership of the oil company additionally raked in fat salaries, without having had experience in the oil business.

Grupo Petersen had no other incentives than take money out of its cash cow, endangering the future of the company in the years 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010.

Between 2008 and 2011, Repsol and Grupo Petersen shared close to US$6 billion in total dividends, when the company's earnings were a mere US$4 billion. Without funds to reinvest and over-indebted, YPF's oil and gas production collapsed, while Argentina lost strategic energy self-sufficiency.

Autist Note: Between 2010 and 2017, the country had to import a whopping US$50 billion worth of energy. Luckily that scenario is improving now, but as you can see here, it could’ve all been a lot faster if it weren’t for these leeches. See this previous article about how Argentina is finally getting closer to energy independence:

Populist saviors come to the rescue

As we’ve seen in the intro of this article, it was around 2012 when then President Cristina Kirchner, widow of the late Néstor Kirchner, decide to expropriate YPF from Repsol.

The arguments were the systematic gutting of the company and no new investments in new developments, resulting in an energy deficit for Argentina that had to import energy vs producing enough for its own consumption.

Who did Cristina Kirchner choose as the guy taking care of the expropriation? Roberto Dromi, who was the same guy responsible for the privatization of YPF in the 1990s. As you can see, Argentina has a lot of revolving doors where money can be made on both sides, as long as you know the right people.

Here’s the kicker with the 2012 YPF expropriation: ALL of the shares of the Spanish group Repsol are expropriated but none of the Grupo Petersen shares of close to 26%.

The Argentine State now had 51% of the YPF shares. The expropriation of the foreign group taking care of Nestor Kirchner’s friendly partner was announced as costing $0, lol, and Grupo Petersen still kept its shares.

Miguel Galuccio, the CEO of YPF at the time of the expropriation, was pleased with the proceedings and mentioned it would give new opportunities for oil and gas exploration in Argentina.

However, Galuccio resigned from YPF in 2016, and founded the oil company VISTA energía. Then, without much development cost his company happened to stumble upon the best oil wells in the country. Seems convenient, but that is food for another story. Back to Petersen.

Can’t just pull a Chavez on Grupo Petersen

As we’ve seen above, Repsol had already settled with Argentina in 2013 and wouldn’t pursue further legal action. Get ready for the best part.

After the expropriation, Grupo Peterson decides to sue the Argentine state in 2015.

Yes, the same group that kept its 25%+ untouched that it got airdropped thanks to the political connections and managing the Santa Cruz funds (and who are starting to look very much like a front company for… those same politicians?), decided that the expropriation was illegitimate and that the Argentine State should be sued over it.

After all, in 2015 there was a new opposition government under Mauricio Macri, so now that Cristina Kirchner was no longer in the picture suing the State would be less of a problem (otherwise it might seem like friends suing themselves).

In other words, these Santa Cruz friends of Grupo Petersen who bought part of the company without paying for it, obtained extraordinary dividends by defunding it and whose shares were not expropriated in 2012, decided to sue Argentina under a new government without their friends in power. Sounds legit.

The claim made by Grupo Petersen was that the company's bylaws were ignored, especially the clause that requires that whoever buys more than 15% of the share capital must make a public offer in Argentina and the United States to those who already own shares or convertible securities of the company.

Burford enters the chat

In order to make it a little less obvious, Grupo Petersen decided to sell the litigation rights of their case to Burford Capital, which bought the litigation rights of the companies Petersen Energía and Petersen Inversora, created in Spain for the purpose of “buying” the 25%+.

The English fund Burford Capital bought the right to sue Argentina under the Petersen case for 15 million euros plus 30% of the compensation obtained from the outcome of the trial, meaning that Grupo Petersen did not sell all of its claims to compensation in the case.

Between the end of 2016 and the first half of 2017, the fund sold its 25% interest in the Petersen trial to an unidentified buyer and earned $106 million. As of December 31, 2017, Burford Capital stated that it had invested a total of $17 million in the Petersen claim.

In mid-2019, Burford Capital sold another 10% on the secondary market, which, along with a few other previous transactions, brought its share of the lawsuit down to 61.25%. Burford explains this number in its statement:

In the Petersen case, Burford is entitled by virtue of a financing agreement entered into with the Spanish insolvency receiver of the Petersen bankruptcy estate to 70% of any recovery obtained in the Petersen case. That 70% entitlement is not affected by Burford’s spending on the cases, which is for Burford’s account; it is a simple division of any proceeds. From that 70%, certain entitlements to the law firms involved in the case and other case expenses will need to be paid, reducing that number to around 58%.

Burford has, however, sold 38.75% of its entitlement in the Petersen case to third party investors, reducing Burford’s net share of proceeds to around 35% (58% x 61.25%).

Final attempt to get the case thrown out & ruling

In 2019, the Argentine Government argued before the United States Court that the purchase of 25%+ of the shares of YPF-Repsol by the Petersen Group in 2008 was made "under a fraudulent procedure" during the government of Néstor Kirchner and "without any significant investment”.

In a harsh brief in 2019, Argentina's lawyers under Mauricio Macri’s government concluded that Néstor Kirchner allowed a series of "false agreements" with Grupo Petersen and that Burford Capital therefore had no right to collect any compensation.

It was all in vain.

After more than seven years of a long and complex judicial process in the United States, Judge Loretta Preska, head of the court for the Southern District of Manhattan, ruled against Argentina in the case for the expropriation of YPF, ordered by Cristina Kirchner during her second mandate in 2012.

In a press release by the BA Times, the damages for the Argentine tax payer will be substantial (emphasis added):

While the judge didn’t set a figure for the compensation, Argentina would have to pay US$7 billion to US$19.8 billion, newspaper La Nación said on Friday, citing estimates provided by the funds.

After the ruling, Burford published this statement on its website (emphasis added throughout):

At a high level, the Court decided that (i) Argentina was liable to Petersen and Eton Park for failing to make a tender offer for their YPF shares in 2012; (ii) YPF was not liable for failing to enforce its bylaws against Argentina; (iii) the various arguments Argentina had made to try to reduce its damages liability from the straightforward application of the formula in the bylaws were unavailing; and (iv) a hearing is needed to resolve two factual issues to enable the computation of damages.

In other words, the Ruling was a complete win against Argentina with respect to liability, with the quantum of what we expect to be substantial damages yet to be determined, and a loss against YPF. However, no additional damages would have been payable had YPF also been found liable.

Now remember: Burford only bought 30% of the claims to compensation and later sold parts of that. So that means Grupo Petersen still has substantial claims after winning the case through Burford.

Final considerations

Grupo Petersen contributed only $110.1 million to get the 25%+ shares. The significant 630 million received by the province of Santa Cruz was used to facilitate and pay for the Repsol-Petersen agreement.

To ensure that Grupo Petersen could repay the "loans" they received, they agreed to distribute 90% of YPF's profits as dividends, instead of reinvesting those profits in YPF, and further agreed to pay an additional $850 million special dividend amount, regardless of actual earnings.

Besides the fact that Grupo Petersen’s share count was left untouched by the expropriation by the Argentine State in 2012, the Ezkenazi clan decided to still sue the State in order to get some more tax funds their way.

YPF went from public to private and back, and in the middle of these shenanigans a small group of insiders made bank.

Today, YPF is worth $4.418 billion dollars, which makes Argentina’s 51% worth $2.253 billion dollars.

For that 51% Argentina will have to pay $20 billion for having expropriated it, little over 9 times more, not counting the fact that Grupo Petersen was able to get their 25%+ thanks to public funds stalled in Switzerland in the first place, which are no longer accounted for as we’ve seen above.

Even though it is clear who were involved in this laundromat of epic scale, and there’s little doubt about the irregularity of the financial loophole in transactions and ownership, it is almost certain that no one will end up in jail or even prosecuted for receiving YPF bags of at least $20 billion+ in FU money at the tax payer’s expense.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

This was confirmed by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, current vice president of Argentina, in a speech she gave in 2014, where she endorsed the former president's decision to expatriate the funds.

Do you think Milei can fix this? What a criminal enterprise putting the Argentinian taxpayer on the hook for this.