2001: Coinmarketcap in real life

The history of the 2001 coin wars in Argentina and how Argentina invented the analogue coinmarketcap

“To truly pull off proper apathy about the stuff (money) would require so much energy, such contrived ideological zealotry, that the indifference would amount to a kind of caring.”

― Lionel Shriver, The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047

Welcome, Avatar! Today we’ll do a deep dive into some of the most interesting (and insane) currency experiments in recent history. Let’s dive right in.

Start of the 2001 crisis

Towards the end of 2001 and the beginning of 2002, Argentina was facing one of the deepest crises in its entire history.

Although it is difficult to establish a starting point for the crisis, it reached its peak in the last months of the government of Fernando de la Rúa, who was governing a society that was pushed to its limit.

During this time, 1 peso was equivalent to 1 US token. The initial trigger of the crisis was the imposition of the "Corralito", on December 2, 2001. The Corralito was a government provision that restricted the withdrawal of cash from banks, designed by the then Minister of Economy, Domingo Cavallo. Depositors could only withdraw a maximum of 250 US trash token per week from the bank.

This had an impact above all on the lower class, mostly unbanked, and the middle class, which was severely restricted in its economic movements. Argentina was a very expensive country in dollars at this time, and people suddenly could only take out $250 per week.

Mid December, the labor unions declared a general strike, and simultaneously violent outbreaks began to take place in some cities in the country’s interior cities and in the suburbs of the Buenos Aires area.

The protests led to a generalized social outburst on the night of December 19, 20011, immediately after president Fernando de la Rúa declared martial law. This announcement caused tens of thousands of people to go out onto the streets throughout the country to express their discontent with the government and political representatives.

The riots lasted throughout the night and the following day, when the order was given to repress the protesters, 39 of whom were killed. De La Rúa had lost credibility and left office fleeing in the presidential helicopter.

In addition to the 39 victims of the repression ordered by the government of De La Rúa to repress the protests, Argentina set a new record right after De La Rúa was forced to leave: 4 presidents succeeded each other in only 11 days. Basically a new president every couple of days.

Argentines still often refer to this with popular phrase: “cinco presidentes en una semana” (five presidents in a single week).

Soon after, the Argentine government had to depeg the peso from the dollar. Just imagine having your money in the bank that used to be 1:1, you can’t get it out, and then you hear that it is now worth 1/3.

That’s what happened to every depositor that wasn’t able to withdraw before the corralito was enforced.

After 2002, the Convertibility Act was voided, and dollar savings were converted to pesos at the new rate, which first equalled 1 dollar to 1.4 pesos, but quickly became 1 US token to 3 pesos.

It is in this chaotic setting that two very interesting economic phenomena surged in popularity, out of sheer necessity: 1) trueque (barter) and 2) circulating provincial bonds in the form of currency.

As more currencies will fail in the near future, the way this situation played out in Argentina could potentially be a blue print for other countries.

Autist note: if you’re interested in the peso/dollar peg of the 90’s and the beginning of this century up until 2002, I recommend reading more about the Convertibility Plan here, and why it eventually failed. Contrary to popular belief, this peg only existed during the first years of the plan (starting in 1991). Until the crisis arrived and significant bank withdrawals began in 2000, the government never needed to use the country's foreign exchange reserves to maintain the peg. Once people started withdrawing en masse, the peso depegged soon after.

Trueque: when currency dies, barter comes back with a vengeance

Most people will know barter is the exchange of material goods or services for other objects or services. It has been a common practice ever since the very first trades between humans. There is no currency involved in the sense that money does not intervene as a representative of the value in the transaction.

According to the liberal current of the economy founded by Adam Smith, barter, as a free exchange between individuals, is a natural practice between human beings for which the surplus (excess of goods that do not need to be consumed) and the division of labor must previously exist (need for a good that is not produced by oneself), which leads to the concept of private property.

The origin of the extensive barter network in Argentina during and after the crisis dates back to May 1, 1995. In Bernal (a town close to the capital), a group of environmentalist neighbors which had already launched some barter markets for organic produce, decided to gather local residents to trade specific products and services arising from the lack of work.

This genesis barter block, or trueque club, originally brought together twenty people, in the style of a self-help group inspired by Alcoholics Anonymous, to "... achieve a higher meaning of life through work, understanding and fair exchange" and "respond to ethical standards and ecological before the dictates of the market, consumerism and the search for short-term profit”2.

As jobs grew increasingly scarce due to the economic crisis that started brewing towards the end of the 90’s, these barter clubs started integrating broad sectors of the popular classes in a short period of time. They surged in popularity by the absence of widely circulating money due to the bank rug pull (corralito) at the end of 2001.

Until their decline in late 2002, you could get almost anything at barter clubs. They were a necessary survival strategy for many people who had no money.

Experiments such as bartering with one's own currency have already occurred before in other parts of the world and also in times of crisis, but what makes the Argentine barter phenomenon so unique is the scale on which these clubs proliferated. This was something not seen before during a local currency collapse, not even in Weimar Germany.

The fact that there simply was no cash or money available due to the corralito, made Argentina a very specific hotspot for barter clubs.

Currency Quasimodos: Quasimonedas

Next to barter clubs or clubes de trueque, another, more “official” phenomenon arose in Argentina, so called quasimonedas (literally: quasi-currencies) during the same period.

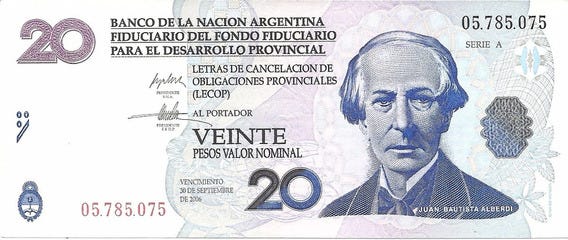

Quasimonedas is an informal name given to the bonds issued in Argentina by the national government and by fifteen provincial governments during the economic crisis that the republic suffered in 2001 and 2002, which circulated in the same way as legal tender.

These bearer bonds could or could not contemplate the payment of interest, with the same dimensions as the legal tender of the country. For the same reason the barter clubs were so popular, these quasimonedas popped up everywhere simply because of the lack of money in circulation.

LECOPs

When in August 2001 the Argentine federal government announced a first issue of LECOP bonds, the reason was supposedly to cancel most of the owed federal tax co-participation.

Because these bonds were circulated at a significant reduction from their face value, anyone who accepted them was destined to suffer devaluation (or inflation).

While LECOPs were meant to replace legal currency (Argentine pesos) when cash was scarce, there were times when LECOPs were not recognized as a valid form of payment – most taxes, for example, could only be paid in pesos, or only partially paid in LECOPs.

Public utility companies often limited the allowed amount to a 70-30 ratio, occasionally limiting payment in LECOPs to 15% of the overall bill.

Moar Quasimonedas

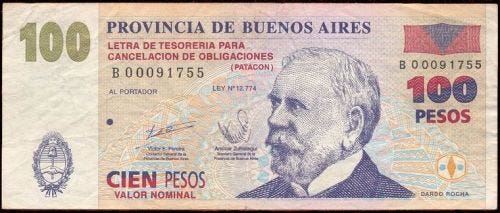

Due to the lack of fiscal discipline in the past, the economic recession and the non-existence of voluntary financing, different provincial governments initiated an alternative issue of "currency substitute" bonds.

This unexpected reaction by provincial governments gained importance until a total of 8,400 million pesos was accumulated, approximately 50% of the money in circulation (!), distributed among fifteen alternative quasi-currencies throughout the country.

Of the total of twenty-three Argentine provinces, fifteen issued provincial bonds that acted as close substitutes for the Argentine peso. The following table presents the distribution for August 2002, at face value, of the provincial bond issuances:

Due to the Convertibility Law, money printing was restricted since 1991. Faced with the resulting lack of liquidity, these bonds were designed as an alternative mode of financing, in the context of the economic crisis affecting the country.

In this way, the national government and the provinces could continue to pay their obligations and in turn partially support consumption, which generated a brief financial relief prior to the end of Convertibility.

As the country recovered its economy since 2003, these quasi-currencies gradually disappeared, until they completely vanished when they were reabsorbed by the issuers. Nowadays they are no more than collectors items.

Groundhog Day: from analogue to digital shitcoins

As you can see from the above, Argentina is the ultimate breeding ground for insane currency policies.

However, if it were up to some local provincial governments, these quasimonedas should be allowed to come back with a vengeance. And this time they will not be issued in their romanticized paper form, but as digital shitcoins.

Currently, Argentina is very close to a new decoupling of the official exchange rate. The gap between the Blue rate and official rate is over 100%, and that can only be sustained for so long.

One more worrying thing is that the international central bank reserves, are -7 billion dollars at the moment:

We are very close to seeing in real time how this will all play out in the near future, and what online currency experiments Argentina has in store for us.

See you in the jungle, frens!

For a video and short documentary of the riots, see this YouTube video. National Geographic is also creating a mini series around the 2001 crisis, you can see a trailer here.

Stancanelli, Pablo, 2002, «Cuando el Estado ya casi no existe. Explosivo crecimiento de los clubes de trueque». Le Monde diplomatique, No. 36, June.

What was the situation with crime during that period?

Out of interest, why did you move to Argentina rather than elsewhere? And what made you leave Europe?