A Shot in the Food

Cow chipping and provincial anti-agro laws

Welcome Avatar! A few recent laws could complicate agricultural production in Argentina in multiple ways, and one of them is literally chipped with conflicts of interest. Let’s dig in.

Argentina is the world's third largest food exporter, and the agricultural sector represents 15.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) and around 10% of yearly tax revenues.

“Export rights” — a euphemism for leeching off the country’s agricultural production in the form of tariffs — have been applied in many different points in Argentina’s past, and this struggle between producers and the State is a constant leitmotiv throughout the country’s history starting in 1862.

Argentina’s farmers are the backbone of the country’s exports, and the government is sure to let them know it too, by levying export tariffs on everything they produce. They’ve had a particularly bad deal ever since retenciones (export tariffs) were introduced again in 2002, after an absence of more than 10 years since 1991.

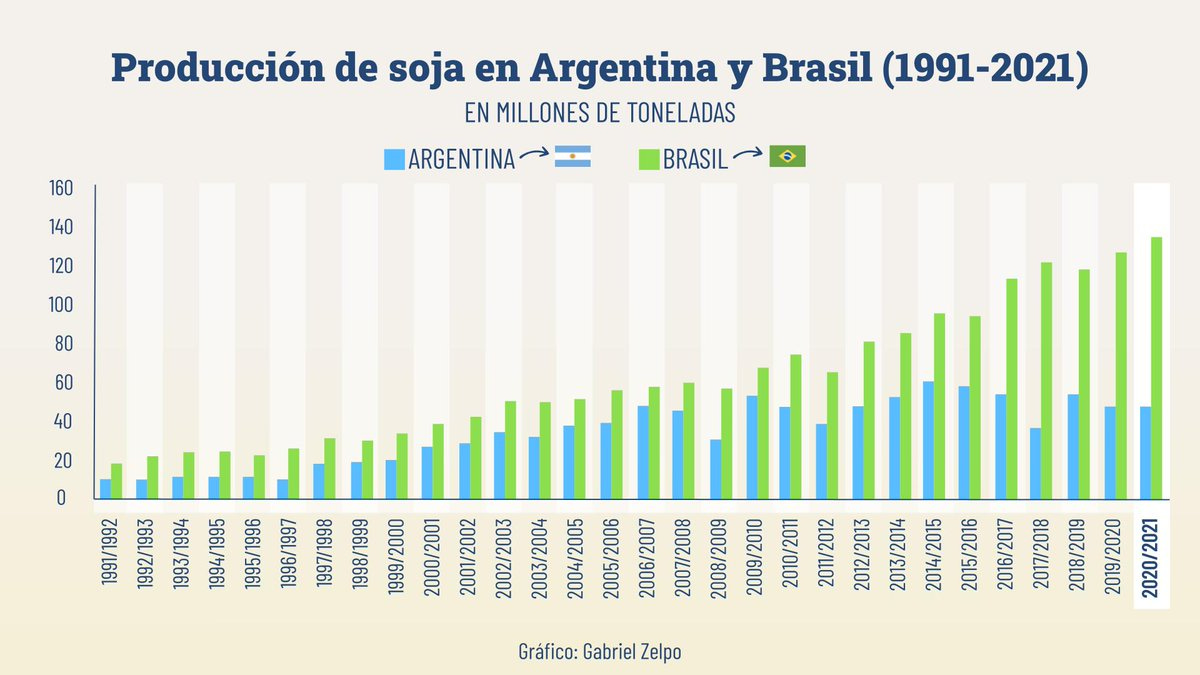

Despite the return of these export tariffs at the start of this century, the macro environment was very different from the current one, and the commodity bull market with souring soy prices in the first decade took production to new highs for Argentina, more than doubling production from a decade before, as seen in the graph below:

What is also clear from this graph, is that once the commodity bull market came to a halt around the 2010s, Brazil started to outpace Argentina significantly in terms of soy production. This happened on multiple fronts, not just for soy, and this is all due to the fact that Brazil did not levy any export tariffs on its agro exports, and Argentina even increased them.

Production stagnated in Argentina, simply because with lower commodity prices combined with export tariffs of up to 33% (!), it became less and less profitable for farmers to invest more and expand production. They have every right to bitch, and beside the fact that the Milei government has not lowered tariffs for the grain sector, which is the bulk of the 10% in Argentina’s tax revenues, new regulations have added some more fuel to their fire.

Pazo, the Cattle Chipper

Last month, the Milei government regulated electronic traceability for livestock by making chipping mandatory for each rancher. The measure will be implemented starting in 2025, and is aimed at cattle, buffalo and deer.

Through resolution 71/2024, the State argued that it wants to achieve the digitalization of the livestock system to improve the export profile and compete globally. The chip will become mandatory from 1 July 2026.

Other countries such as Paraguay and Brazil will implement a similar system on a mandatory basis from 2025, while Uruguay, the US and Australia already use it.

Producers will have access to a free app which they can use to manage their cattle stock from a cell phone, with the information generated by the electronic devices.

This sounds logical given the fact that consumers in many countries demand traceability of their food and want to know “where stuff comes from”, and in theory it will make livestock management easier.

However, that does not seem to be the primary reason behind this sudden demand for more supply chain transparency. Whenever there is a new mandatory regulation around farming and ranching in Argentina, it is time to start paying attention.

Just look at the 50M+ cattle that needs to be chipped in the map above. That is a lot of chips. The State will be in charge of providing these chips to ranchers.

The one government official in charge of the chip implementation has been caught with his hand in the cookie jar filled with conflicts of interest: Juan Alberto Pazo, Secretary of Production Coordination at the Ministry of Economy under minister Luis Caputo.

The sequence of events around Pazo’s chip initiative is interesting, to say the least.

In August, Pazo fired the vice president of the National Service of Agri-Food Health and Quality (SENASA), Sergio Robert. Robert had refused to implement the electronic individual traceability of cattle, and was replaced by chip-friendly Néstor Osacar.

With that obstacle out of the way, Pazo moved forward. Because no hay plata, the government will use a loan from World Bank to apply the chips:

The government said that the plan will be implemented through a loan from the World Bank, so producers will have free access to the electronic device.

Before launching it, Senasa will hold international tenders. It is estimated that the cost of each electronic device or chip that will be used will be around US$0.75.

Now comes the $35+ million dollar question: which company will be in charge of chipping the herd of 50+ million units in Argentina?

The answer is Invernea: a company in which Pazo is a majority shareholder. Besides Pazo, the company’s management team includes Nicolás Caputo — son of the current Minister of Economy Luis Caputo:

In May of this year, the Official Gazette reported that Invernea was reconverted into a public limited company (SRL), with Pazo owning 90% of the company despite being a civil servant, and just a few months later after getting rid of the last obstacle, the road is clear for the first big order, financed with a World Bank loan.

Seems legit.

La Pampa & Entre Ríos on Suicide Watch

From cattle to crops, a lot of shifts are happening that might endanger the 10% coerced extraction to the federal coffers from producers.

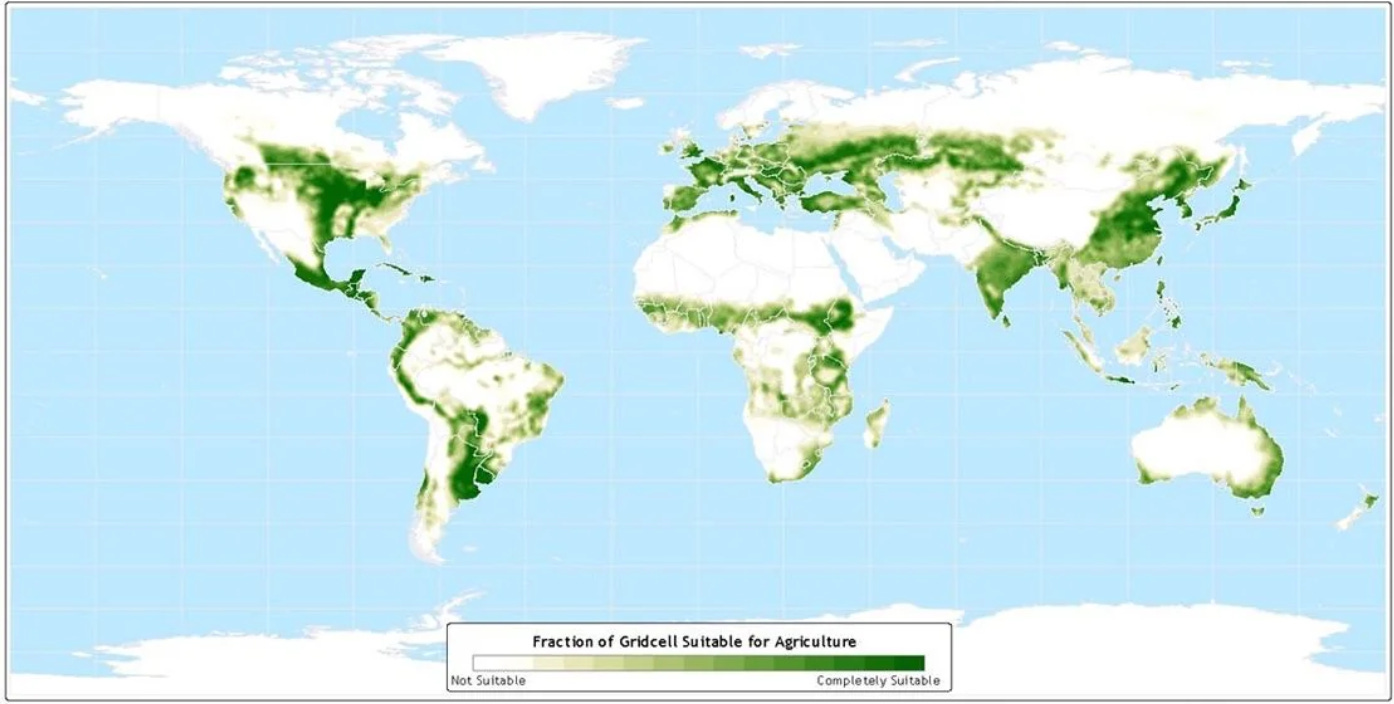

Law 3288 on Comprehensive Pesticide Management adopted by the provincial government of La Pampa, one of the most fertile corners on this green earth together with the corn belt and the Ukraine, was approved in 2020 and will be regulated and come into force this year.

Now, anyone knows that pesticides and herbicides are not ideal, but at the same time mass-scale agriculture would not be possible without them.

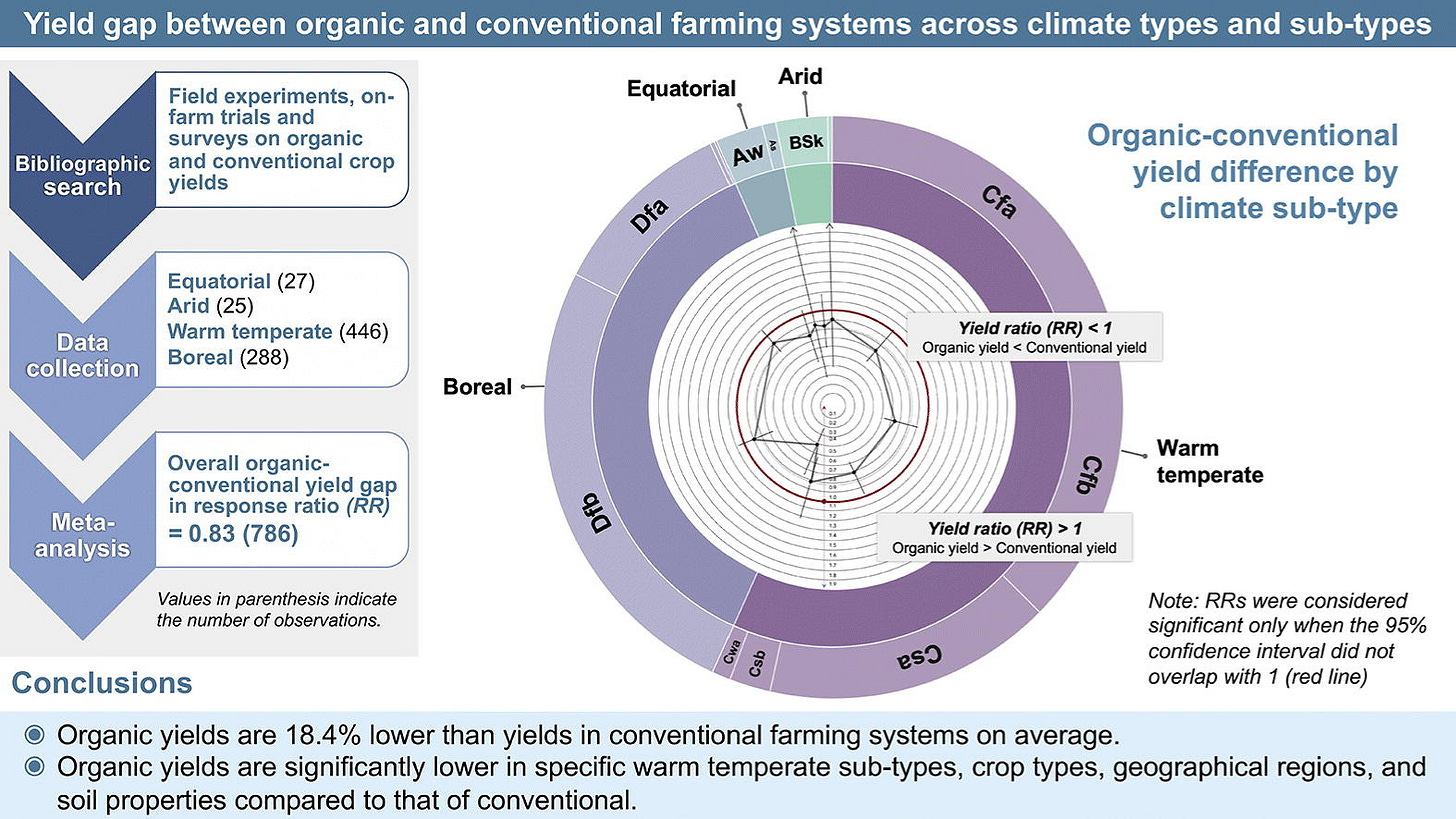

Organic farming is fine and well if you have to feed a few villages, but with the volumes needed to feed the world, it is simply counter productive and backwards. Harvest yields are dramatically lower for organic farming (about -18% on average).

The new law in La Pampa includes a prohibition of the application of phytosanitary products within 500 meters from the urban area of the 44 agricultural towns in the province, which would generate a loss in turnover of almost $53 billion pesos ($46 million USD).

With the restriction of application to 3,000 meters from the urban area imposed by the law, the situation is even more fatal: the affected area in the 44 agricultural localities would reach 210,000 hectares, not counting the restricted area of water spaces. The estimated production loss would amount to $276,301,535,500 pesos ($240 million USD).

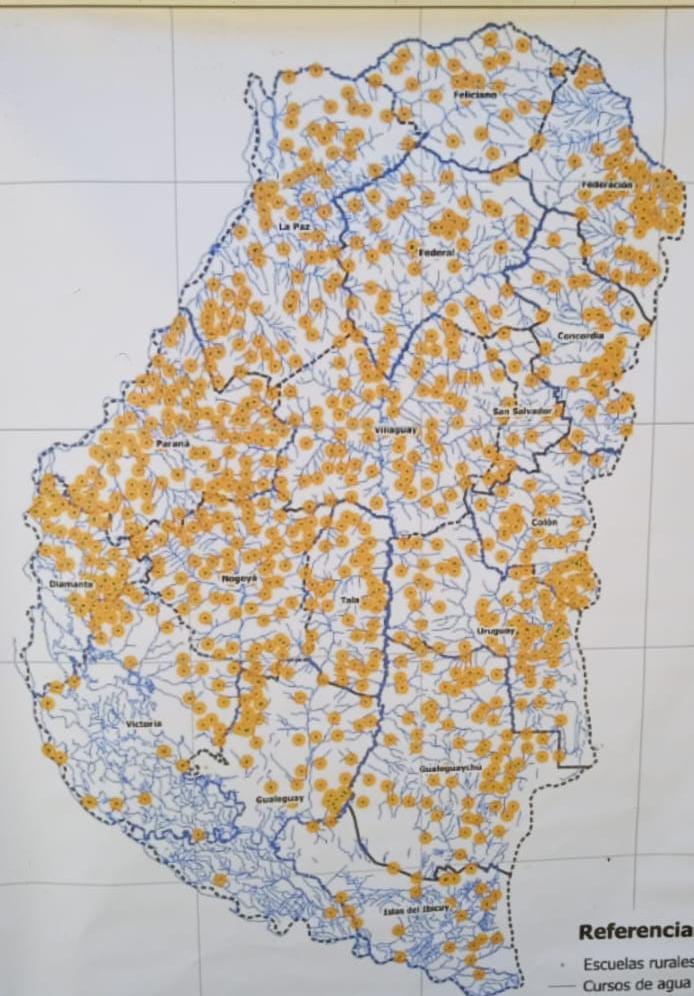

Simultaneously, the Chamber of Deputies of Entre Ríos gave partial approval to a bill that regulates the use of phytosanitary products in the province, declaring the adoption of good practices in this area to be of “public interest”.

The new regulations in Entre Ríos establish three zones for the regulation of fumigation: 1) the Exclusion Zone, where there is “absolute restriction” on the application of phytosanitary products; 2) the Buffer Zone, which allows the conditional use of some products; and a 3) Special Zone for schools and health centres.

Autist note: these provincial laws are diametrically opposed to the vision of Milei’s government, and this is a case of federalism playing out in a negative way. There is not much the national government can do if these provinces decide to go down this road. Read more about Milei’s federalist model here:

The exclusion radii vary between 15 and 500 metres, depending on the proximity to settlements and the characteristics of the product.

The law also promotes “ecological intensification” in exclusion zones, incentivizing the use of sustainable practices through fiscal and economic benefits. The provincial authorities plan to introduce a framework of sanctions for violations, including warnings, fines, confiscations and closures, among others.

So basically if your neighbor complains about pesticides, the provincial government will be able to seize your farm after a few warnings. How very ecological.

Conclusion

The battle between producers and local (and federal) governments is only just beginning. 2025 will be a crucial year for the agricultural sector in more than one way: farmers in La Pampa and Entre Ríos will get hit by destructive new regulations and ranchers will need to start chipping their cattle with Pazo chips.

Even though traceability is a net positive that was also celebrated by many ranchers, Pazo’s direct involvement in its implementation does not fail to revive the good old Menemist memories of the 1990s, when similar deals tied to government officials and the private sector were the norm.

The provincial laws in La Pampa and Entre Ríos are dealing a killing blow to the agricultural sector if nothing changes and they are enforced as stands. These laws impose enormous bureaucratic burdens, violate property rights, criminalize agricultural production and will seriously affect all agricultural producers in both provinces, especially the smallest ones.

This all comes on top of the Milei government not giving any clear timeline of when it will decrease or completely ¡afuera! the sky-high export tariffs on the most important grain exports. If that does not change soon, continued support for Milei from the agro sector could start to decline in 2025.

On the other hand the government knows that there are no viable alternatives at the moment — Kirchnerism has always been a sworn campo enemy, whereas Macri does not seem to have a strong enough platform to capture their votes either — , and so the chokehold on producers continues.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

![OC] Number of Cattle by Country : r/dataisbeautiful OC] Number of Cattle by Country : r/dataisbeautiful](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EoIz!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F24eb9252-fb0e-4370-9be1-676132a839fa_7000x4305.png)

Well, guess I'll need to stop complaining so much here in the US.

I am sorry but 18 pct higher yields is not worth destruction of ecosystems and health with pesticides