Argentina: Arbitrage Paradise

The story of how Argentina was built on smuggling and parallel markets and how politicians keep it this way.

Welcome Avatar! Today we will go over the history of arbitrage opportunities, deeply ingrained in Argentina’s DNA, which often go hand in hand with restrictions and limitations for the majority of the population.

Throughout most of the country’s history, Argentina has consistently fought internal battles demanding the opening —or closing and limiting— of trade and commerce.

A select few make bank on evading custom authorities, tariffs and sky-high import taxes, while others who aren’t able to fool the custom’s Swiss cheese get to pay the price.

As Mariano Moreno, one of the founding fathers of the country, pointed out in his book “The Representation of the Landowners” (emphasis added):

“What could be more ridiculous than the sight of a merchant vociferously defending the observance of the laws prohibiting foreign trade at the door of his shop, where nothing but clandestinely introduced English goods can be found?”

— Mariano Moreno in 18091

This quote will always be current and can be used at any point in time. One only has to swap the country of origin of the most popular products that Moreno is referring to, and the quote will be describing the current situation.

A Blueprint Since Inception

Smuggling activity in Argentina has been a popular pass-time and survival method for merchants since the 16th century. Back then, smuggling consisted of illegal trade and trafficking without the traffic being reported or authorized by the colonial authorities.

The borders of the Spanish colonial Empire were even more permeable than they are today, and Buenos Aires and other cities established on Argentine soil became potential avid customers for the products brought in from ships operated by non-Spanish Europeans.

The smuggling came mainly from what is now Brazil, then a colony of Portugal. Officially, such trade was illegal, since the cities of the Spanish colonies were only authorized to trade with their metropolis, but due to this situation of necessity, local rulers did not usually offer any notable resistance to its implementation.

Smuggling played an important role in the political struggles that began during the emergence of the Argentine State.

There was a constant power struggle between the political authorities, the merchants who benefited from smuggling and the pro-independence Creoles.

These merchants opposed opening trade to other countries, while the Creoles, influenced by the new ideas of liberalism, maintained that trade should be allowed.

This power struggle around international trade and commerce is the blueprint for the power dynamics of international commerce.

As a rule of thumb whenever people start talking about change in Argentina, it is always a good reminder that since the country’s independence, the only thing that has changed in over 200 years are the labels of the political parties attached to one side or the other.

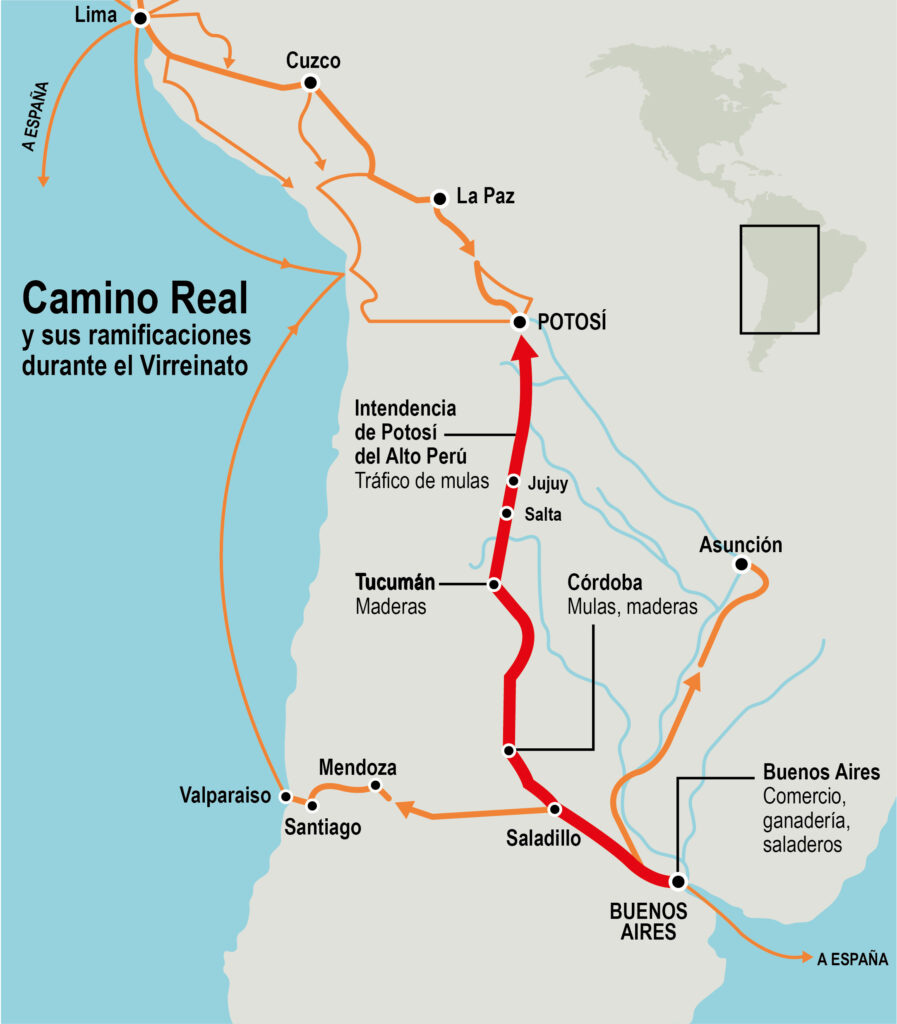

Lima and Buenos Aires

During colonial times the Spanish crown decided that all the wealth generated by the southern colonies had to pass through the port of Lima. The economic objective was to benefit the merchants of that city and their local patreons, who paid important “commissions” to the crown.

Buenos Aires was assigned the mission of watching over the Lima route. The whole route didn’t make much sense: the goods were sent from Spain to the isthmus of Panama and from there they went to Lima, to be transported by land to the consumer markets further down south.

And as is usually the case thanks to the dynamics Human Action, when a bureaucrat comes up with a brilliant idea from the confort of his desk, the market finds a better way. In this context, the solution Argentina came up with was smuggling, the first national industry.

These operations produced an abundance of circulating money that benefited a large part of the Buenos Aires population, who ended up looking at smuggling with complacency or actively participated in it.

Parallel Customs Offices: a mirage of free trade

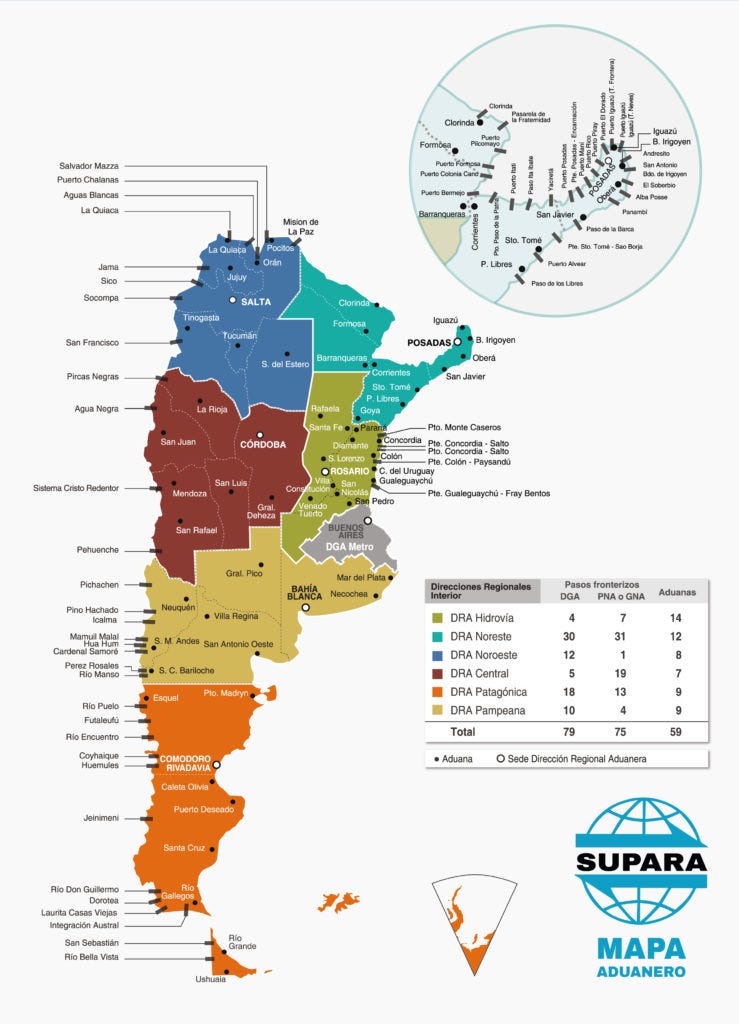

Customs offices play a big role in trying to control the influx of goods from different parts of the border, and as you can imagine with Argentina’s immense territory, there’s a good deal of border crossing that are wide open for informal crossings.

“Parallel customs”, or Aduanas Paralelas in Spanish, is a phenomenon that stretches throughout Argentina’s relatively short customs history. As saying dictates: hecha la ley, hecha la trampa (once a law is created, so is a way to outsmart it).

Basically the concept of Parallel Customs consists of a group of smugglers, often times with custom officials or agents involved, smuggling large quantities of products in and out of the country at a significantly lower commission rate than the official tariffs.

Tariffs are so absurdly high in Argentina that these parallel custom services pop up almost immediately in times when the tariff rates on exports and imports are bumped up.

To give you an idea of how ridiculous and “anti commerce” the current rates are: for many imports rates are around 50% (especially for cars, electronics, and other products that could be produced or assembled in Argentina). This results in quality products being close to twice as expensive as in most other countries.

This is a problem that plagues most Latin American countries though, so it is not unique to Argentina. Brazil and Uruguay have similar import taxes on these type of items. Chile and Paraguay are your best bet to get new tech at a similar price compared to the EU or the US. You can already smell the arbitrage.

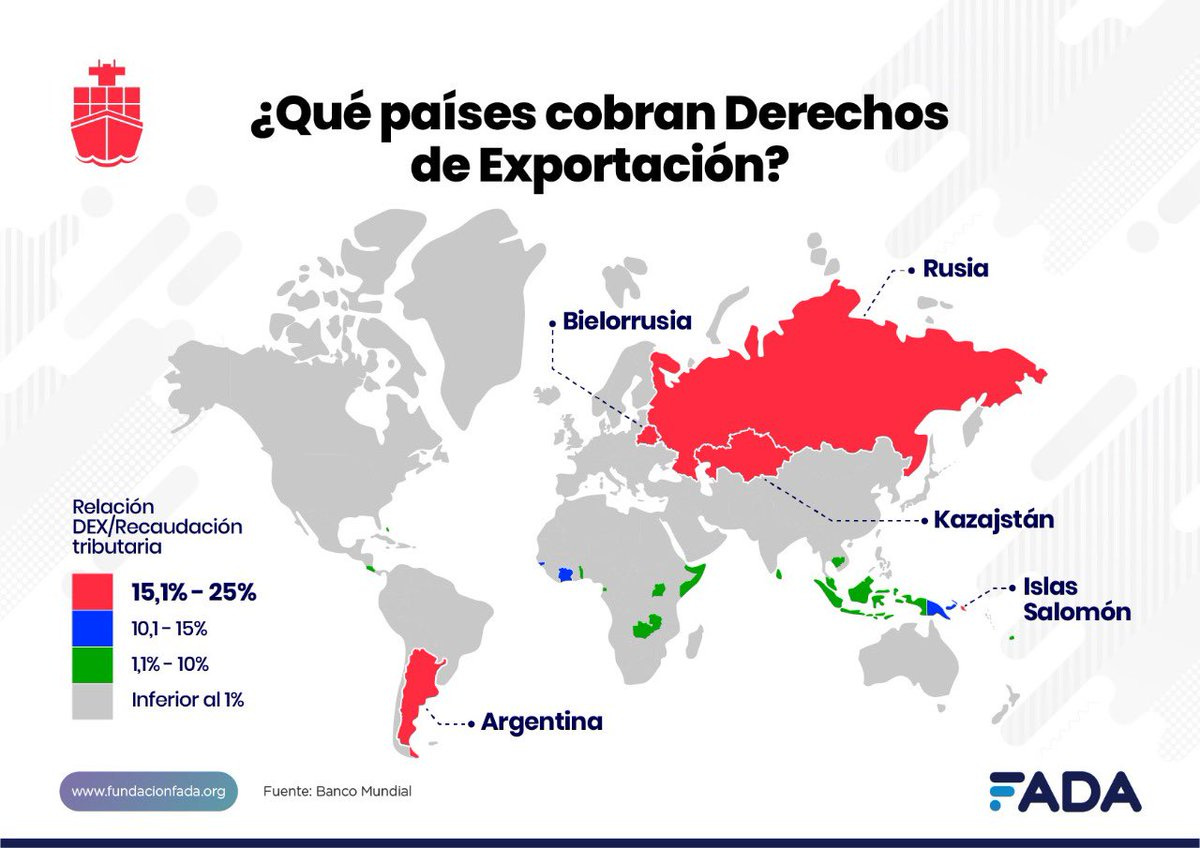

Besides these hefty import tariffs, Argentina has additional export tariffs that not a single country in the region implements (see map above), and the list of countries that do is a list you do not want your country to be on.

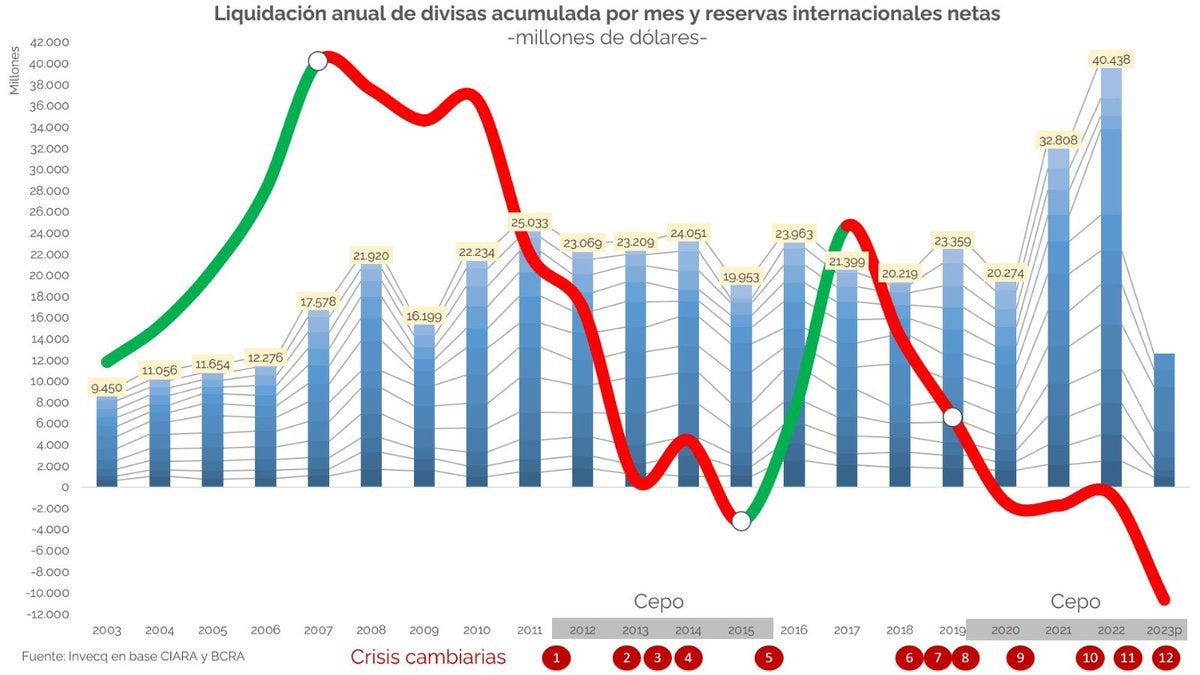

These export tariffs are the Central Bank’s main cash cow, since Argentina is such a big grain and food exporter. The government secures billions of dollars for its coffers annually through these tariffs, slowly bleeding producers dry.

Despite all these juicy dollars coming in at a fictitious rate (usually a rate just above the official exchange rate, which means that producers get hammered with another hidden tax, due to the fact that they need to pesify these dollars at those rates, whereas in reality their dollars would be worth more), liquid BCRA reserves keep tanking.

Below you can find an example of a soy producer’s yield after export tariffs, for a full cycle of soy in 2022/23. Taking into account an average yield for the cycle equal to that of the previous harvest (28 qq/ha), the State (National, Provincial and Municipal) rakes in about $723 USD/hectare, while the producer in would be left with $95.94 USD/hectare:

Basically producers are working for the State for 10.6 months of the year. The other 1.4 months, they get to keep. How generous. And during the last harvest with its extreme droughts, those 1.4 months ended up giving a negative result:

You can understand why there is zero incentive to invest more in better yields, new machinery (which has to be imported and is also taxed at 50%), etc.

This is one of the big issues holding the Argentine economy hostage.

No wonder that the export market is one with the biggest parallel custom system. This has to involve multiple bureaucrats and government officials who have to look the other way, since were talking about tons and tons of food and other exports. This isn’t simply an iPhone you stick in your boxer while crossing the border.

The numbers can run well into the millions (and in some cases of substantial exports it can run close to a billion dollars).

In April of this year, another criminal organization acting as a parallel customs office was dismantled in Salta, smuggling soy, chia, and other grains out of the country.

The Paraguay Connection

Paraguay plays an important part in contraband to and from Argentina and Brazil. If you thought the lack of state enforcement was great in Argentina, it’s nothing compared to Paraguay.

Many cars in Paraguay do not have license plates, and estimates are that about 60 percent of the vehicles that travel on Paraguayan avenues and roads (about 600,000+ units) are of illegal origin. Paraguay also doesn’t require car insurance, which makes driving in whatever even easier.

In 2001, not even Paraguayan president Luis González Macchi, was spared from this very common practice in Paraguay. A luxurious armored BMW for ordinary use by the head of state, purchased in 1999 for $80,000 USD, turned out to be contraband and its title forged.

The Argentine province of Misiones is the holy grail of Aduanas Paralelas, with many billions of dollars in exports flowing to Brazil and Paraguay under the radar every year.

According to AFIP (Argentina’s IRS) data, in 2021 about 110 thousand tons of soybeans entered the province from other parts of the country. However, only 20 thousand were absorbed by the formal demand. A black hole of 90 thousand tons, just for what is recorded.

Getting the soy out of the country and selling it below the market price in dollars in Brazil or in Paraguay gives producers a way better return compared to paying all the export tariffs and basically working for the State.

The Uruguay River is narrow and zigzags, which means it's easy to cross and difficult to control. Below is a video of a stolen Hilux crossing the border into Paraguay, and a raft filled with subsidized Argentine fuel heading the same way.

Young residents of these border localities are usually in charge of these crossings. They are called “chiveros” and in one day they earn as much as they could earn in several weeks with other formal jobs.

As you can see, the border leaks in many different areas. All this wouldn’t be necessary if the State would be just a little less gready, but on the positive side it does provide for some excellent content that shows us exactly how the concept of Human Action works in practice.

Final Considerations

As you can tell, you can legislate commerce and trade to death, but you can’t legislate smuggling out of the Argentine DNA.

This hasn’t changed since inception, and it is very unlikely to change now. The political elite actively participates in these trades, and in a way enables them by creating new barriers, which people subsequently always find ways around.

The creativity of Argentines around every new roadblock that is pulled up by politicians is limitless, and it is a game of Whac-A-Mole that smugglers have been winning for well over two centuries.

Trade restrictions come and go, and as history has shown time and time again, Argentina thrives during times when restrictions are eliminated.

Let’s see if the economic tides in the next few years will only lift the rafters smuggling merchandise across the Paraguayan border, or if they will benefit the rest of the population as well. That outcome, unfortunately, is mainly in the hands of lawmakers.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Translated from Spanish: ¿Qué cosa más ridícula puede presentarse que la vista de un comerciante que defiende a grandes voces la observancia de las leyes prohibitivas del comercio extranjero a la puerta de su tienda, en que no se encuentra sino géneros ingleses de clandestina introducción? - from the book La Representación de los Hacendados.

I've been in Argentina since 2002. I really wish I met you earlier. I can't believe you've been there since 2005. I've never really wanted to hang out with any expats because many don't take the time to learn about Argentina or it's rich history. You embrace it like I do! Reading many of your posts are stuff we have mentioned over and over again.

It's so refreshing reading stuff like us that weren't born in Argentina we understand it, embrace it, and love it more than Argentines. I don't get it some times. Argentines have mostly given up on their country while guys like us show them they MUST believe in it for a better tomorrow!

Great article as usual. The paid subscription is SO worth it. How long have you loved Argentina Mara?