Argentina's Nuclear Ambitions

A deep dive into Argentina's nuclear energy history from Perón to Milei

Welcome Avatar! While the Vaca Muerta region tends to be the lead protagonist when it comes to the energy sector in Argentina, nuclear energy has been a constant focus of many different governments throughout the past 80 years. We’ll go over Argentina’s nuclear history, and Milei’s present plans.

Argentina's nuclear adventure starts with President Juan Domingo Perón. At that time, only the United States possessed the formula to unleash the energy contained in atoms. Perón wanted to take the lead in nuclear energy and was willing to invest a fortune to make sure the second country in terms of nuclear energy would be Argentina.

On February 24, 1947, The New Republic wrote on its cover: “Exclusive, Perón’s Atomic Plans” and stated that Werner Heisenberg had been invited by the Perón government and that “with a large source of uranium discovered in Argentina, this nation is launching a military nuclear research program to break the Pandora’s box of atomic energy.”

The article also emphasized that Perón's proclaimed third position — a neo-fascist political ideology representing a third position between the capitalism and communism — concealed his intention to establish a sort of Fourth Reich on Argentine soil.

Autist note — read more about Juan Domingo Perón’s relationship with fascism and the nazi’s in particular here:

Invited to settle in Argentina after the war, Heisenberg was unable to travel due to the opposition of the Allied powers to ceding their monopoly on atomic secrets.

Huemul Island

Perón then decided to hire Austrian physicist Ronald Richter, a physicist who had worked in Berlin at Manfred von Ardenne’s laboratory, participating in the Third Reich's nuclear project. However, Richter would turn out to be a thorn in Perón’s side that would only be removed after scamming the former President and the country out of millions of dollars.

Ronald Richter secretly arrived in Argentina in mid-August 1948 as part of a group of German engineers, technicians, and test pilots led by aeronautical design and development expert Kurt Tank. At the time, Tank was in charge of the Pulqui II project, an Argentine airplane that was never mass-produced.

On August 24, at Tank's recommendation, Perón met Richter, who managed to convince him of the possibility of obtaining energy through the process of controlled fusion, something we now know to be impossible with the technology of the time1.

Richter not only dazzled the general with his verbosity and fantasies, but also won over Brigadier César Ojeda, Minister of Aeronautics, who was present at the meeting. It was during this interview that he explained his idea of generating energy through nuclear fusion, something that had not been achieved anywhere in the world. With this, Argentina would be one of the world's major powers and would have enough energy to meet the energy needs of Perón’s second Five-Year Plan.

The Island In Bariloche

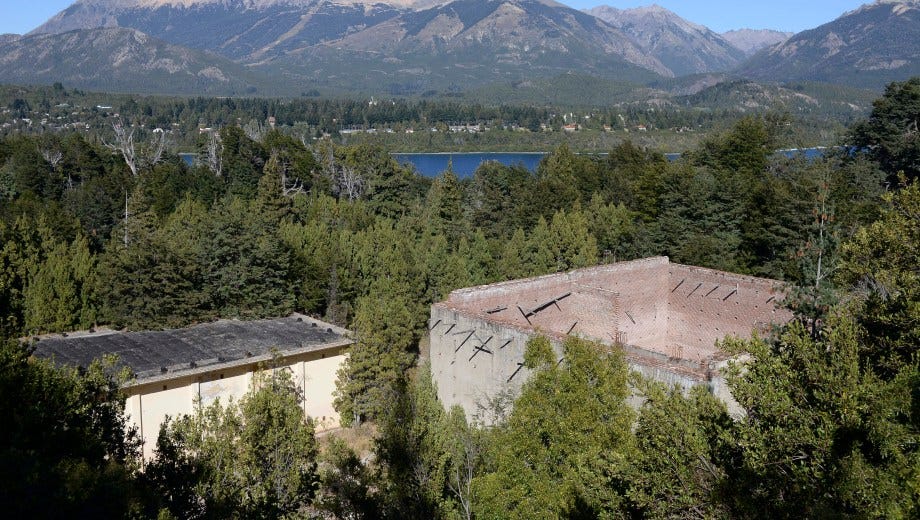

In June 1949, the decision was made to push forward with the construction of a major complex of facilities in Bariloche — in the province of Río Negro —, with its main laboratories and instruments to be installed on Huemul Island.

Colonel Enrique González, a personal friend of Perón's, a pragmatist, efficient administrator, and not prone to fantasies, was placed in charge of the project. The chain of command was similar to the United States and the Soviet Union, where the highest nuclear authority was in the hands of the military.

The Huemul Island project was initially financed with reserved funds and in complete secrecy. González soon insisted on institutionalizing the administrative process and convinced Perón to do so. On May 31, 1950, Perón signed the decree creating the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA) and appointed González as its secretary general. The CNEA would report directly to the Presidency. Its objective was to oversee all atomic research.

Meanwhile, Richter was supposed to be working on the scientific part of the Huemul Island project, but he was more preoccupied with spending the funds Perón had allocated to it. The Austrian physicist drove around in a convertible Cadillac, a personal gift from general Perón, and he was one of the most well-known celebrities of the time.

In total, Richter had received US$15 million in funding — which would roughly be the equivalent of US$350 million today. Finally, after a two-year spending spree, Perón would be able to share some good news.

Perón's Announcement

At a packed press conference on March 24, 1951, Perón announced to the country and the world that Argentina was now ready to unleash atomic energy and obtain radioisotopes through thermonuclear reactions.

Argentine newspapers reported the spectacular news with headlines such as: “World Sensation over Perón's Announcement on Atomic Energy” and “Argentine Announcement on the Production of Atomic Energy Had a Profound Repercussion in Washington.”

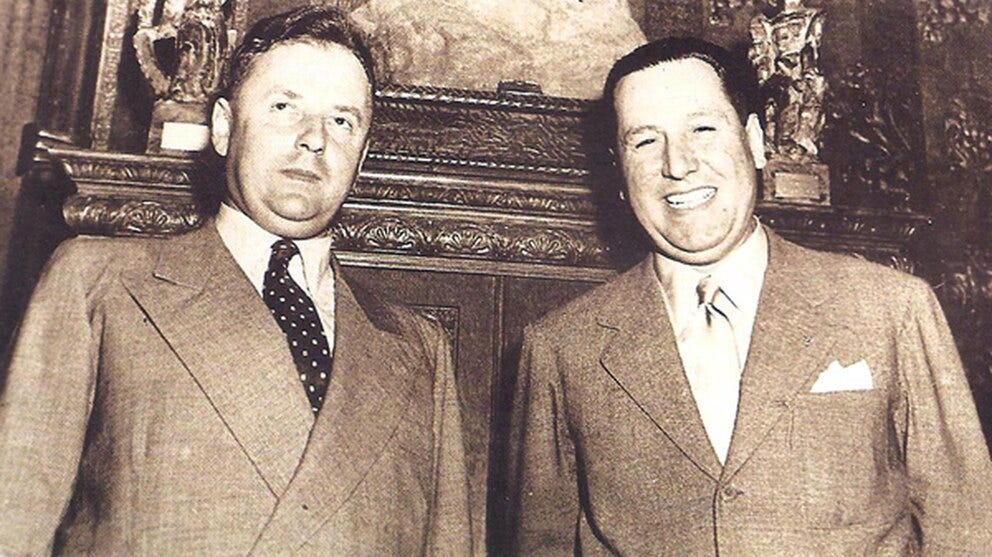

On March 28, four days after the momentous announcement, Ronald Richter was solemnly honored in the White Room of the Casa Rosada. Perón and his wife Evita, who was already ill, awarded him the highest decoration of Peronist Argentina, the Gold Medal of Loyalty, and an honorary doctorate from the National University of Buenos Aires:

Perón's announcement caused a stir in the world press. The declaration that Argentina had mastered “the secrets of the atom” had shocked the world and had even been published in newspapers such as The New York Times on that same March 24:

“President Perón said, according to The Associated Press, that uranium was not used in the Argentine method of producing atomic energy. The source of atomic energy produced in the United States and elsewhere is uranium. Officials and scientists in the States were skeptical about the Perón announcement.”

And it turned out that this healthy dose of skepticism was warranted. Ronald Richter had convinced Perón that he could create small suns on earth, and Juan Domingo Perón believed this. In an article a few days later, the NYT concluded that Perón’s announcement could not be taken seriously:

“The announcement of President Juan D. Perón of Argentina that on Feb. 16, 1951, in a pilot plant on Huemul Island "thermonuclear experiments were carried out under conditions of control on a technical scale" would be readily accepted by physicists if nothing more had been said.

But President Perón and Dr. Ronald Richter, the physicist in charge of the experiments, added that the thermonuclear reactions in question "are identical with those whereby the sun releases atomic energy." This being so, enormous temperatures (at least twenty million degrees centigrade) are necessary.

No earthly material could stand up under them. The statements quoted contradict each other, and it is for this reason that physicists here and abroad do not take President Perón seriously.”

Professionals who had had a working relationship with Richter also didn't take the announcement seriously, and that was one of the reasons why his entire house of cards started to come down.

CNEA secretary general González had received skeptical opinions from other physicists and had unsuccessfully attempted to supervise Richter's “advances”. In February 1952, González resigned in protest against Richter and his lack of results.

This was the sign for Perón to start an internal investigation and see what the supposed physicist Richter had actually been working on for all these years on his little excluded Patagonian island.

The Audit

The last thing you need when you’re running a scam is an official audit that will unveil it. After dumping millions of dollars into his nuclear Fugazi, that audit eventually arrived for Richter's island in Bariloche. To find out what was really going on, the government created a Huemul Project Oversight Commission, which visited the island in 1952. This was the beginning of the end for Ronald Richter.

One of the commission’s members was José Balseiro — in whose honor the institute located at the Bariloche Atomic Center is now named —, and his opinion on Huemul was damning. Richter’s arguments failed to withstand the slightest theoretical scrutiny and Balseiro could not find a single tool or device on the island that would be able to generate or contain a controlled thermonuclear reaction, lol.

The commission also discovered that Richter had never taken any notes or published any scientific work, and it turned out he also didn’t have any real connection with the international or national scientific community. The thesis with which he had obtained his doctorate in Prague was a fake, which had later been disavowed by the academic authorities. Richter had completely rug pulled Perón2.

Surprisingly, Richter did get off rather lightly given the size of his deceit. Once evicted from the island, he was imprisoned for only five days and was later expelled to the Buenos Aires town of Monte Grande, where he dedicated himself to raising ducks and chickens. He lived there until his death in 1991, all the while refusing to ever speak Spanish, a language he claimed was for “monkeys descending from palm trees.” Up until his last days Richter still continued to repeat that he had the formula for creating small suns on earth like he had tricked Perón into believing.

In the remainder of this article we will go over Argentina’s more recent nuclear energy history, and Milei’s nuclear plans.