La Dama del Cemento

The story of how Amalia Fortabat became the richest woman in Argentina

Welcome Avatar! Today we will go over María Amalia Sara Lacroze de Fortabat’s story, also known as the “Cement Dame”, and how she became the richest woman in Argentina, together with some insight into the current state of the company that made it possible: Loma Negra.

Early Life

Amalia Lacroze was born on August 15, 1921 in a historic mansion in the heart of Recoleta on Rodríguez Peña and Charcas (today Marcelo T. De Alvear). Thanks to her aristocratic family, she learned to speak English and French before Spanish.

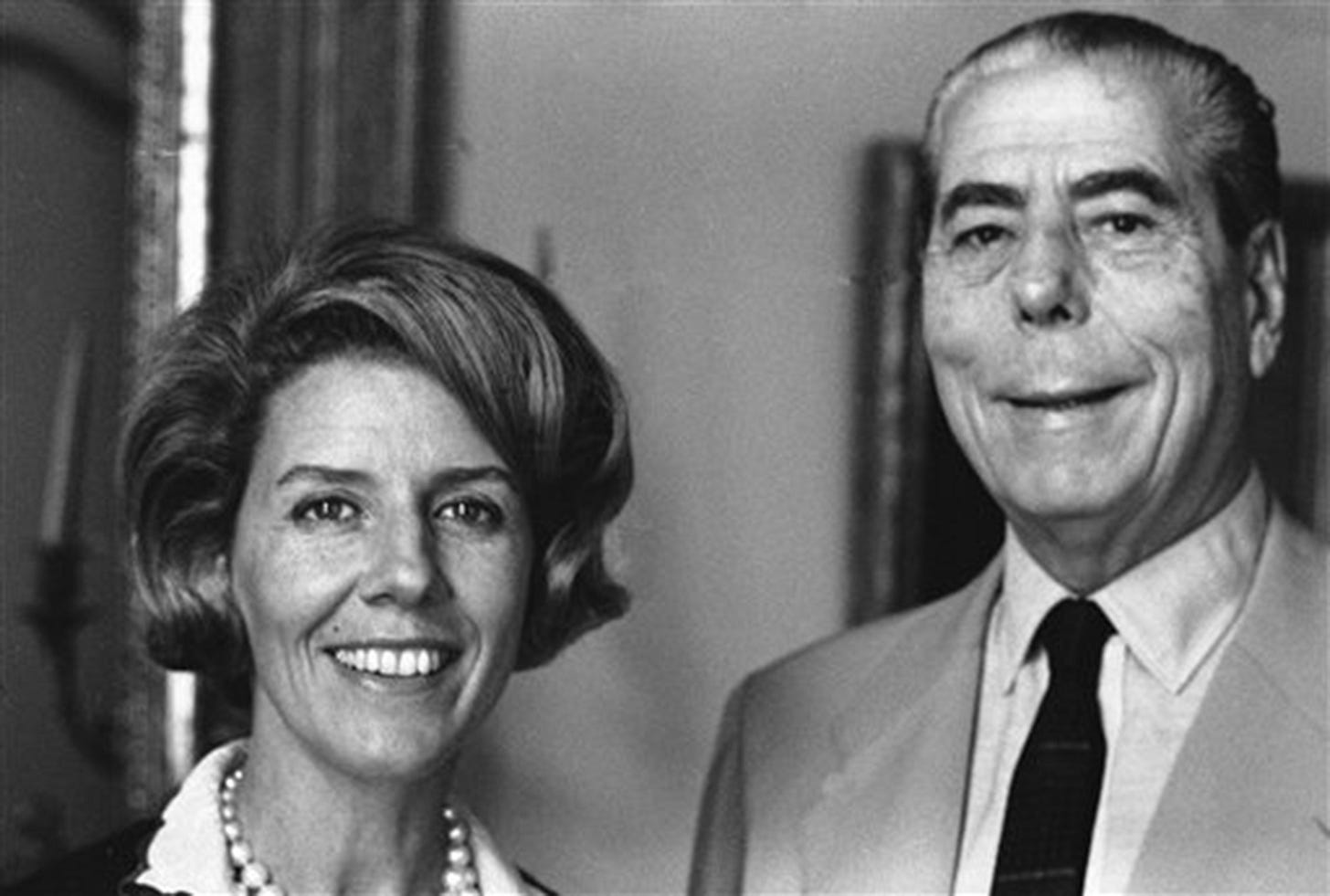

In 1942, At the age of 21, she married for the first time. The marriage with Hernán Lafuente, the father of her only daughter, María Inés, did not last long.

With a war running hot in Europe and tango in Buenos Aires, Alfredo Fortabat, founder of the emblematic cement company Loma Negra, confessed to her that was in love with her, despite the fact that he was 27 years older.

During Juan Domingo Perón's second term in office, in 1954, Congress approved a law that allowed divorced people to remarry. This is how Amalia Lacroze and Alfredo Fortabat were able to marry the following year.

At the time, Loma Negra was already the biggest cement company in Argentina and Latin America, and the company continued to grow throughout the 1950s and 60s.

The first important project in Olavarría, the headquarters of the cement company, was nothing less than the development of a nursery school for the children of the company's employees, which housed some sixty boys and girls.

The Mortar Cementing her Wealth

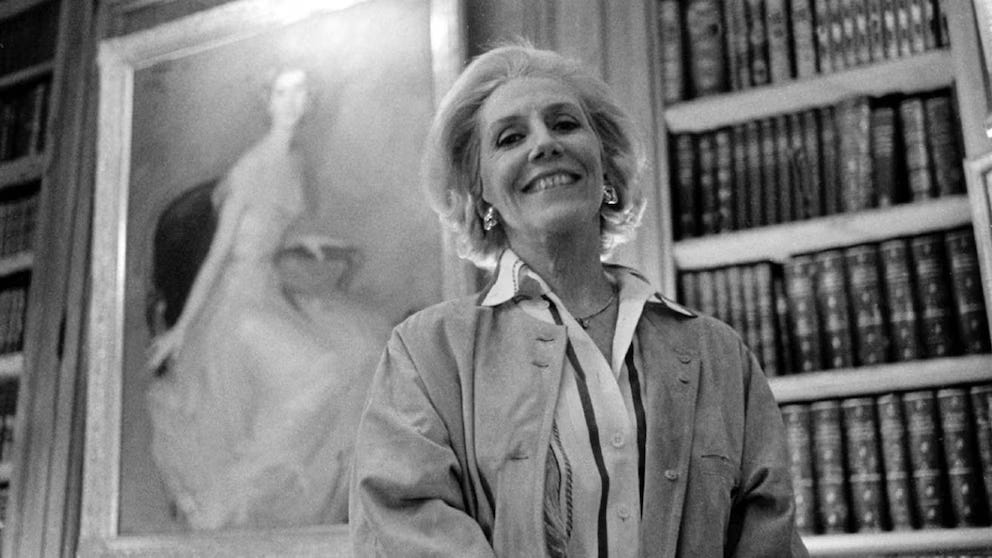

Amalia received one of the hardest blows of her life when she was widowed in 1976 at the age of 55. However, at the same time that blow was softened by inheriting a large fortune, which she managed to triple rapidly.

After learning the ropes of the cement business — and getting some help from the Military Junta in government projects —, she became the richest woman in Argentina with a fortune estimated at US$1.8 billion.

Autist note: despite the fact that many judges and courts have tried to link Loma Negra to forced disappearances and arrests of Loma Negra employees during the military dictatorship (1976-1983), there have been no convictions and from what I have found so far, most cases were random arrests or assassinations of workers, which happened across Argentina regardless of their employer. The biggest case in the Province of Buenos Aires, investigated the links between the state repressive apparatus and the board of directors of the cement company in the arrest of six employees who were planning to go on strike and the kidnapping and murder of lawyer Carlos Alberto Moreno, but no clear links were ever proven.

Under the direction of La Dama del Cemento, Loma Negra consolidated its growth, adding production plants in San Juan, Neuquén and the province of Buenos Aires.

She knew how to sit down at a table of men and negotiate with them with as much or more wisdom and authority than they did. Two of her close friends, Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller, spoke to her as an equal.

In 1976 she inaugurated the Alfredo Fortabat and Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat Foundation, renamed the Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat Foundation in 1988, with the aim of promoting and carrying philanthropic initiatives in addition to the promotion of scientific research. It is estimated that she donated more than 40 million dollars to charitable works.

Divide and Conquer

There were of course some footnotes to all that charity, as is usually the case in a country like Argentina where big industrial conglomerates work hand in hand with whatever government is currently in place to protect their interests.

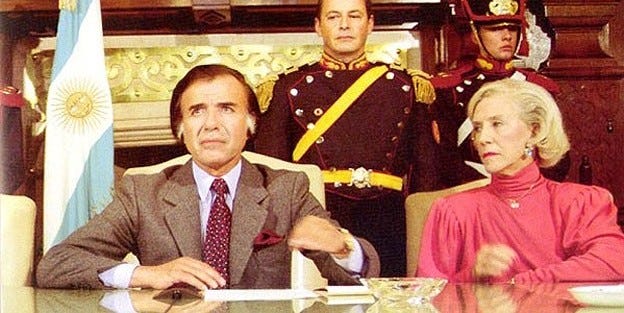

After the dictatorship during Alfonsin’s presidency and later in the 1990s during the presidency of Carlos Menem, Loma Negra consolidated its position as a market leader while participating in illegal price agreements and market distribution together with a handful of other construction firms.

From 1981 onwards, these firms began to fix prices above those that would have normally arisen from free competition, establish production levels corresponding to each firm and agreeing on the prices to be quoted for public works tenders and thus guarantee that one company would be the winner of the process1.

Typical “hunting in the zoo” behavior in Argentina, a tale as old as time.

In 1999, Luis Jorge Capurro, Loma Negra's representative in the Cement Companies' Negotiations Club, wrote a book that was not published but served as the basis for the investigation and fine of almost 310 million pesos by the National Competition Commission (back then, the exchange rate was pegged to the dollar).

He stated that:

“Until the time of the Malvinas War, the board of directors of the Portland Cement Manufacturers Association handled the division of the market among the companies in a very reserved manner, but the situation that the country was going through was very worrying and it was necessary to sharpen their wits as much as possible.

The solution was commercial. It was established that the sales managers would meet periodically in order to be able to make quick, agreed-upon solutions also regarding prices.

In this way, the Round Table was formed, which is still intimately called the Club or Clubcito, given its small number of members. Everything was arranged in this Club, and afterwards the meeting was crowned with an important lunch or dinner, accompanied by an ample selection of drinks of course.”2

In the Clubcito’s distribution of market shares, Loma Negra had 48%, while four other companies hovered around 10-12%, and the leftovers were divided between two small smaller firms.

The Clubcito companies exchanged information on a monthly basis and based on production deviations, it was decided whether they should slow down or speed up, completely bypassing real market supply and demand.

Price agreements based on the area and the distribution of the market by quotas harmed consumers who ended up paying overprices. Capurro said that:

“Loma Negra obtained the agreement of the Roundtable to have preference in the supply of public works by putting pressure on the participation deficit they had at that time. With this argument they coerced to be able to supply the Rosario-Victoria bridge and the access routes to the city of Córdoba.”

You might start to understand why so many Argentines are weary of wealth, because so much of it is amassed in similar ways throughout the country’s history. Of course there are many exceptions, but those never seem to get the same kind of media attention.

Autist note: for another billionaire story in Argentina, here you can read about how Aristotle Onassis, who was not born with a golden spoon, made his fortune in Argentina going from rags to riches:

End of the Line

By the mid-2000s, Loma Negra continued to suffer from a series of economic difficulties due to the crisis in the construction sector, aggravated by its debt to foreign banks, which had tripled due to the 69% devaluation of the local currency.

The Cement Dame tried to cushion the losses by auctioning off more than twenty works of art during those years, but in 2005, at the age of 84, Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat sold the Loma Negra cement company to Brazilian company Grupo Camargo Corrêa (now under private holding company Mover Participações), who took control of the Argentine firm in exchange for $1.025 billion dollars.

This amount that also included the debt of the group and its subsidiaries, estimated at 200 million dollars — a big chunk of that was the ruling of the cartelization fraud against Loma Negra explained above.

Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat died of natural causes at on February 18, 2012 at the age of ninety in her private home on the 12th floor of the building at Avenida del Libertador 2960, after a sick bed of over 30 days.

Loma Negra Today

Up to this day, Loma Negra is still the leading company in the production and marketing of cement in Argentina, with a market share of nearly 45% and a production capacity of 7.6 million tons of cement per year.

The company, founded by Alfredo Fortabat in 1926, is close to a 100 years old and is one of the Argentine companies with the greatest public recognition.

In 2023, turnover amounted to $422,161 million with an EBITDA of $100,351 million. It shipped 6.4 million tons of cement, which is a figure that will not be reached this year due to the collapse of sales due to the halt in public works and the drop in activity that impacts construction.

Cement dispatches remain below the level of the pandemic and the pre-pandemic. In October, they suffered the sixth drop so far in 2024, with a -20% year-on-year drop.

The monthly decline was -1.1% compared to September and a contraction of -26.2% so far in 2024, according to the latest statistics published by the Portland Cement Manufacturing Association (AFCP).

Construction activity in Argentina is slowly picking up this year, but still below historical averages.

Current Developments

Loma Negra’s stock market debut took place in November 2018, when the cement company raised US$953 million from the sale of 251 million shares (representing 49% of the total shares). The operation became the second largest initial public offering of an Argentine company since YPF raised US$2.7 billion in 1993.

Earlier this year, Grupo Camargo Corrêa started with a plan to divest from the cement business. The first step in this direction was taken last June, when InterCement — which brings together the group's investments in the cement business — filed for bankruptcy in Brazil and divested its subsidiaries in Mozambique and South Africa to the hands of the Chinese company Huaxin Cement Co.

The current value of Loma Negra would be around USD 700 million, 300 million lower than what Grupo Camargo Corrêa originally paid back in 2005. InterCement agreed to an exclusivity period for the negotiation of the sale of Loma Negra with Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional (CSN) — the largest steel company in Brazil and one of the largest in Latin America.

This exclusivity agreement was postponed on successive occasions throughout 2024. Last week, the Argentine company announced a new extension through a statement to the Stock Exchange, until December 16.

In the midst of InterCement's negotiations with CSN, an Argentine businessman interested in the cement company had appeared on the scene: Marcelo Mindlin, owner of Pampa Energía.

A possible acquisition would allow him to integrate the production chain with his construction company Sacde, whose works include the construction of the Néstor Kirchner gas pipeline and the reversal of the Norte gas pipeline, together with Techint. But the exclusivity contract with CSN keeps Mindlin away from this possibility.

We will likely know in December if the sale to CSN will go through, or if it gets postponed again. Everything indicates that this time, it will happen.

In an ideal world the exclusivity agreement for CSN does not renew and Pampa Energía gets to place a bid on Loma Negra, bringing the company back in Argentine hands, but the odds of that happening are low.

Autist note: you can read another more recent family business story in the wine sector here:

The Fortabat Legacy

The Cement Dame did not only manage mortar: her private art collection was extensive and can be visited in Puerto Madero.

The Colección de Arte Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat museum was inaugurated in 2008, and has more than 150 works by renowned international artists such as Rodin, Warhol, Turner, Dalí and Blanes, as well as Argentine artists such as Badii, Berni, Quinquela Martín, Noé, Pérez Celis, Fader, Soldi and Xul Solar, among others.

Amalita’s penthouse located at Avenida Libertador 2960 was listed for sale at a price of US$12 million earlier this year, with a surface of more than 2,000 m2, a gym, a private elevator. Not sure if it’s sold already so feel free to enquire.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

This type of cartelization corruption between private companies agreeing on higher bid prices for public works is very common worldwide, and even happened in a “low corruption” country like the Netherlands, which came as a “shock” to everyone except the politicians and the construction companies. Lol. — for more info on that 2002 bouwfraude case here.

Original quote in Spanish can be found here.