Paraguay and the Triple Alliance War

An overview of the bloodiest conflict in Latin American history that shaped the country borders we know today

Welcome Avatar! Today we will go over one of the bloodiest conflicts in Latin American history: the Paraguayan War (1864-1870), which left a death toll of up to 400,000, wiping out close to 90% of Paraguay’s male population, and 50% of the country’s total population.

Outside of the Southern Cone not many people know about this war, and it was news to me before moving here.

The worst war in the history of Latin America has its origins in an internal conflict that arose in Uruguay and that quickly escalated to a regional level.

Some older historians sustain that it was encouraged by the commercial interests of the British Empire, but that theory has been discredited in recent years.

It all started in 1864, only a few decades after the countries of South America declared their independence from the European powers. It was also the time in which the borders of these newly formed neighboring nations were still being defined.

Francisco Solano López

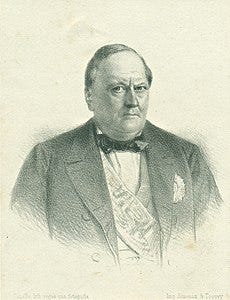

The main protagonist of this story on the Paraguayan side is Francisco Solano López, the second president of Paraguay.

His father Carlos Antonio López was the first president of Paraguay as a country. The independence of Paraguay was declared in 1842, and little by little the countries of the region started recognizing the country’s independence.

The first government to do so was from Bolivia in 1843, later the governments of Chile and Brazil followed.

However, the main diplomatic drawback was with Argentina. When dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas received the independence documents in 1842, he stated that Paraguay was a rebel province of Argentina, and that therefore the recognition of its independence was absurd.

While his father was the first president of Paraguay, Francisco spent his early years in Great Britain and France, making many important business connections for his war efforts later on, and meeting his spouse Elisa Alicia Lynch, who would join him to Paraguay and stay with him up until the very (bitter) end.

When his father died in September 1862, he designated his son Francisco Solano vice-president of the Republic.

Francisco took office immediately and convened a Congress of Deputies in order to appoint him President of the Republic, assuming the position on October 16th that same year, for a period of ten years.

After becoming president, Solano López started leveraging the many business relations he had made in Europe, contracting British engineers and companies to come and work in Paraguay, and pass on their knowledge to local apprentices.

These professionals worked much in the way of the guilds in Europe, and within a decade many new local engineers were formed in Paraguay. Economic growth, general business and industrialization was picking up in the country.

Origins of the War Drums

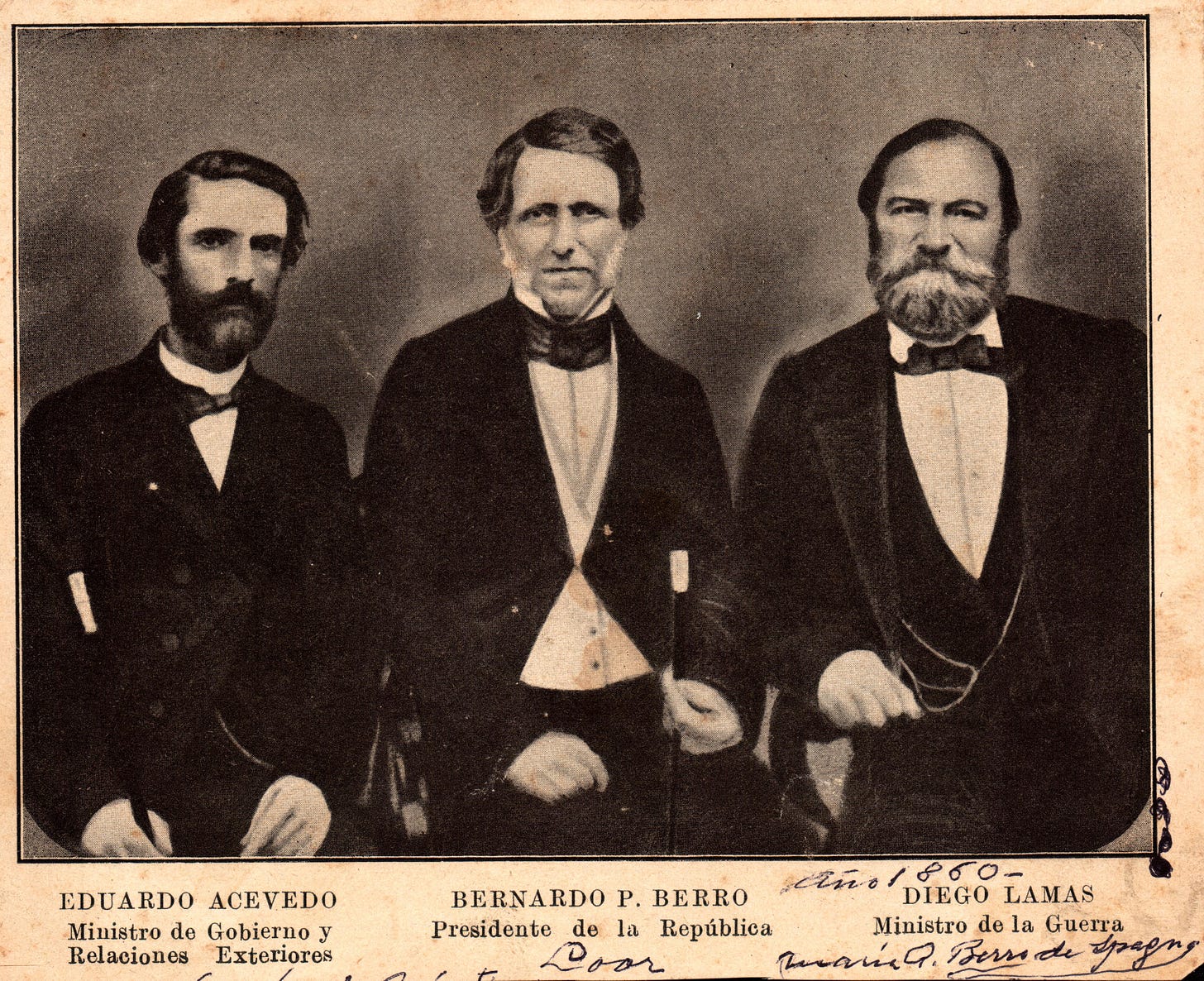

In 1864, The detonator that triggered the war was a fight between the two traditional parties of Uruguay: the National Party, which was in power at that point in time, and the Colorado Party.

The Uruguayan government of Bernardo Prudencio Berro was Paraguay's only regional ally, guaranteeing it an outlet to the sea. Although in practice before the war started, Paraguay mainly used the port of Buenos Aires to access the Atlantic Ocean.

On the other hand, the Colorados, led by General Venancio Flores, were supported by Imperial Brazil.

For this reason, when Flores led a revolution to overthrow Berro —with the help of Brazil—, Paraguayan president Marshal Francisco Solano López decided to jump to the defense of the Uruguayan government.

There was one small problem: Paraguay didn’t have borders with Uruguay, so the only way to reach Uruguay would be by river, it couldn’t be done by land.

War with Brazil

Solano López ordered the capture of a Brazilian merchant ship and invaded the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso, which Paraguay and Brazil disputed.

At this point in time, Paraguay was still exclusively at war with Brazil.

López took advantage of the weakness of the Brazilian forces in Mato Grosso, which allowed him to triumph on that front, but by initiating that action he postponed his entry into the civil war in Uruguay, where Berro’s successor Aguirre and his supporters were his only possible allies.

Although the plan prepared by the Paraguayan high command did not specify it, everything indicates that the ultimate objective was to take the city of Cuyabá, capital of Mato Grosso.

However, the advance by land stopped almost 400 km from Cuyabá, and the Paraguayan army would never reach Mato Grosso’s state capital.

The Brazilian reaction to the invasion was very slow: a column organized in São Paulo in April 1865 only arrived in Coxim at the end of that year, almost a year after Paraguay’s invasion. The Brazilian army successively occupied the towns evacuated by the Paraguayans, and some regions were not recovered until June of 1867.

Paraguay comes to Uruguay’s aid: a fatal mistake

López still intended to send his troops to Uruguay in defense of his allies who were by now busy fighting a civil war. In order to get his troops there, he needed to cross the Argentine province of Corrientes. From there, things started to escalate quickly.

Despite its initial victories in Brazil, Paraguay could not achieve decisive action given the enormous extension of the Brazilian territory.

López requested authorization from the Argentine president Bartolomé Mitre for Paraguayan troops to cross through Argentine territory into Uruguayan territory.

By freeing Uruguay from Brazilian influence, López hoped to find an ally and a place of great strategic importance for Paraguay: an route to the sea for the landlocked country.

Argentine president Mitre did not agree to what was demanded by López for two reasons: if Argentina allowed the passage of troops from a belligerent state in this war, it would be directly involved in it. The other reason was the old relationship of affinities between Mitre and the head of the Uruguayan Colorado party Venancio Flores, a declared enemy of López.

López's entry into the war in Uruguay was too late: his Uruguayan ally Aguirre had already resigned after seeing that the situation was hopeless against Argentina and Brazil backing his adversaries.

Nonetheless, López believed that he could still save the White Party, something he could not: On February 20, 1865, Flores and the Brazilian army entered Montevideo to take control of the country.

The start of the Triple Alliance

On April 13, 1865, the Paraguayan campaign against Argentina began: Paraguayan troops captured Argentine ships in the Paraná River and occupied the Argentine city of Corrientes.

Argentina established the headquarters of the Allied Army in the city of Concordia. From there, an army commanded by Uruguayan President Venancio Flores advanced ―with the participation of Brazilian contingents― in search of Paraguay’s divisions, the first of which was defeated in the battle of Yatay.

Many captured Paraguayan soldiers were turned into slaves in Brazil or incorporated into the allied armies, forced to fight against their homeland.

These initial losses for Paraguay marked a radical change in the course of the war: the Paraguayan troops had to abandon Argentina in a hurry to go on the defensive in the Paraguayan region located between the Paraná and Paraguay rivers.

After withdrawal, the Paraguayan forces attempted some counterattacks south of the Paraná River, during which they were victorious at the Battle of Pehuajó. The only result was to delay the invasion of Paraguayan territory by the Triple Alliance forces.

1865-1870: 5 long years of defending Paraguay

Initially, Solano López had hoped that the population of the northern provinces of Argentina would rally behind his cause. When this support failed to materialize, he made the strategic mistake of operating with two columns so separated that they ended up being three formations and one squad, all autonomous from one another.

On the other hand, his army commanders accumulated very serious tactical errors. Under these conditions, defeat for Paraguay became inevitable.

By order of President López, Paraguayan troops began with looting of animals and movable property as they withdrew from Argentine territory, destroying what could not be taken.

The looting and destruction had different intensity at the time the war took place. During the first months, until approximately July 1865, there was no deliberate or systematic destruction, but only a few isolated outbursts for consumption by the invading army.

In the last months of Paraguayan occupation of Argentine territory, looting and destruction intensified, combined with the burning of rural establishments.

As you can imagine, this did not win over the hearts and minds of the Argentines for the Paraguayan cause.

The Paraguayan defensive lines located in the south of the country were formidable and during the course of these 5 years, the Triple Alliance troops would be surprised time and time again by the excellent defense tactics implemented by the Paraguayan army.

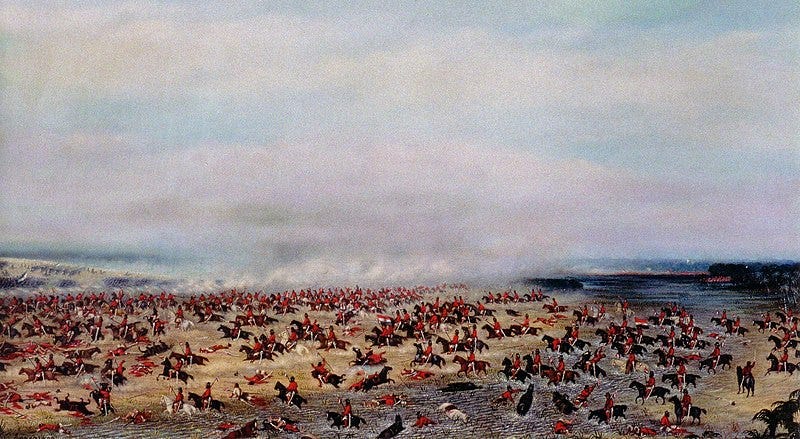

On April 16, 1866, an allied army of just under 50,000 men began to cross the Paraná River, entering Paraguayan territory. Two days later, allied forces took the Itapirú Fortress on the right bank of the Paraná River , reduced to rubble by cannon fire from the Brazilian fleet.

One month later, a large portion of the Paraguayan army was destroyed in the Battle of Tuyutí, losing 6,000 men plus a similar number wounded. It was the largest and bloodiest battle in South American history. From that moment on, the Triple Alliance troops started to gain more ground in Paraguay.

Peace talks to no avail - fight to the end

Early September of 1866, President Solano López met with his Argentine counterpart in search of a peaceful settlement, but the effort was unsuccessful due to Brazil's absolute opposition to making peace with Paraguay without its total surrender.

Mitre, like the Uruguayan Flores, who also attended the peace talks, was committed to Brazil by the Secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance, signed on May 1, 1865, not to sign any separate treaty with Paraguay.

The Final Phase of the War

Many remarkable battles followed, with some large setbacks for the Triple Alliance especially during the Battle of Curupayty, where they lost a considerable amount of forces to the excellent Paraguayan defenses.

After a resounding victory in May at Tuyutí and a swift conquest of the Curuzú fort in early September 1866, the allies intended to do the same with Curupaytí, the formidable fortress right on the banks of the Paraguay River, defended by some 5,000 Paraguayan soldiers.

In that battle the allies suffered 4,000 casualties and the Paraguayans, who could not be reached from their unconquerable position, lost only 92 men.

But in the end it was just a matter of time and persistence before a total defeat on the Paraguayan side. It was the last victory of the Paraguayan army of Francisco Solano López before his total defeat.

Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay pushed on relentlessly, with Marshal Solano Lopez eventually retreating further and further into the interior. Brazilian troops kept in pursuit of Lopez, who was shorter and shorter of men available to fight for his cause.

The majority of the Paraguayan male population had already perished closer to the end of the war by 1870.

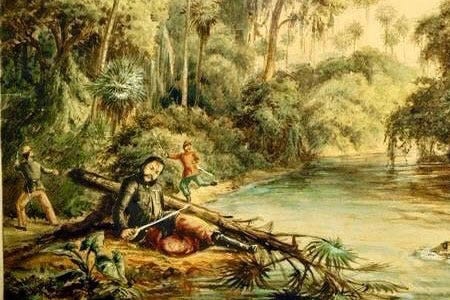

Child Soldiers in Itá Ïvate and Acosta Ñu

Things started looking very gloomy after the Battle of Itá Ïvate. The battle began at six in the morning on Christmas Day, 1868, and ended at ten in the morning on the 27th.

Less than six thousand Paraguayans, many of them adolescents, women, and children with false beards so they looked more like men, faced more than twenty-four thousand enemy soldiers. The allies lost, between dead and wounded, less than a thousand men.

Except for two hundred men who took refuge in the nearby forests, Marshal Solano López lost almost all that was left of his army there.

The US Ambassador to Paraguay was a witness to the Itá Ïvate battlefield, and would later state:

“It pains me to say that more than half of the Paraguayan army is now made up of children from ten to fourteen years of age. This made the battles on December 21 and the days that followed truly terrifying and heartbreaking. These little ones, in most cases completely naked, returned from combat in great numbers, dragging themselves, mutilated in an inconceivable way. There seemed to be no place for them and so they wandered helplessly towards the barracks without crying or groaning.”1

One of the reasons why so many children died on the different battlefields was a decree of February 14, 1869 by which López declared all twelve-year-old males adult and therefore fit for combat.

One of the final battles of the war is still remembered every year in Paraguay as the Día del Niño: 16 August, 1869, the Battle of Acosta Ñu.

That day, more than three thousand Paraguayan children were killed in the presence of their mothers.

It’s hard to find a parallel anywhere else in military history worldwide for what happened that day, it was full carnage: 20,000 Brazilian soldiers attacked 3,500 terrified children without holding back, something that can hardly be called a battle, it was full annihilation at this point.

In his book Genocidio Americano, Brazilian historian Julio José Chiavenato writes why remembering this battle is so important (emphasis added):

"Acosta Ñu is the most terrible symbol of the cruelty of that war: children from six to eight years old, in the heat of battle, terrified, clung to the legs of the Brazilian soldiers, crying, asking that they not be killed. And they were slaughtered on the spot.

Hidden in the nearby jungles, the mothers observed the development of the fight. Many of these women took up spears and came to command groups of children in resistance to the slaughter. Finally, after a whole day of fighting, the Paraguayans were defeated.

At sunset, when the mothers came to pick up the injured children and bury the dead, Brazilian Count d'Eu ordered the brush to be set on fire. At the bonfire children could be seen running until they fell victim to the flames.

The sacrifice of these children perfectly symbolizes how the war became relentless and without concessions. Both on the side of Francisco Solano López, forming battalions of children, and on the Brazilian side, which was not ashamed to kill them."

López was the main responsible for the criminal massacre of Acosta Ñu. Cornered in Azcurra, he needed to distract the enemy to escape and continue his flight towards the mountains.

He used these children as a shield in order to take advantage of the time that the Brazilians wasted in killing them to disappear from again, along with those who were still following him.

This is the End

Finally, with the allied invasion and López's armies decimated, the tragic epilogue was imminent. Solano López reached the confines of Amambay in an area called Cerro Corá, when on the banks of the Aquidabán Nigüi stream he was killed by Brazilian forces on March 1, 1870.

A Brazilian soldier shot Solano López in the heart, who died shouting: "I die with my country!2" The Marshal was left face up in his gold-embroidered blue pants and his tall black boots.

His son Panchito was also killed, after he refused to surrender.

His widow, Elisa Lynch, buried her husband López and her son on the spot and marched back to Asunción with the rest of the 254 prisoners.

Total Casualties

Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay lost about 120,000 men. But Paraguay really came out as the loser of the war, having fought with tooth and nail (and children) to defend its country against the Triple Alliance.

For Paraguay it was not just a military defeat, it was a massacre that some historians consider a genocide. The approximately 280,000 Paraguayan casualties represented more than half of the population of that country.

It is important to note that not all blame can fall on the Triple Alliance: Paraguay’s leader Solano Lopez really did never ever surrender, as we have seen above, even rallying children from the countryside to put them in ditches as cannon fodder waiting to be slaughtered, which eventually ended up happening.

Autist note: What we still miss is an epic high budget movie about this conflict, showing the war from all angles, including internal conflicts (indigenous tribes murdering other tribes, using the war as an excuse to settle decade old rivalries). Just throwing that idea out there in case any Mercosur bureaucrats who could get their hands on cultural funding happen to read this piece.

Aftermath

Before the conflict, Paraguay maintained territorial disputes with Brazil and Argentina.

After the war, Paraguay lost a large part of the territory it claimed, which represented more than 150,000 square kilometers (and more than 25% of the territory that Paraguay considered as its own).

Brazil kept the territory it claimed in Mato Grosso and Argentina managed to annex the current provinces of Formosa and Misiones, the latter effectively creating the only direct border between the two giants Argentina and Brazil.

Furthermore, Brazil occupied Paraguay for six years and demanded war reparations.

Final Considerations

The War of the Triple Alliance is filled with controversial historical facts, as is the case with most wars.

Those who condemn the three allied countries maintain that it was an aggression planned by Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay, with British support and inspiration, to annihilate Paraguay.

Others defend the Triple Alliance, arguing that Paraguay took the initiative by occupying the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso in retaliation for the intervention in the civil war that was taking place in Uruguay and by occupying the Argentine province of Corrientes without prior declaration of war.

From today's perspective, what stands out is the incomprehensible feat that a war with this relationship of forces so adverse to Paraguay could have lasted five whole years.

For Paraguay this is still one of the events that shaped its history more than anything else. It stalled growth, and the Triple Alliance made sure that a quick resurgence from the ashes could never again pose a threat to their borders.

One of the indirect consequences of the war, was that Paraguay did not see the large-scale migration that occurred in neighboring Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay.

It wasn’t all bad for the men who survived: on average the ratio of men to women was 1 man for every 4 women, and up to 1 per 20 in some parts of the country.

All joking aside, the Paraguayan War, or Triple Alliance War is one of the conflicts that shaped what these four countries are today, even though it is not talked about often.

In a way, this war held planted the seed that binds the starting countries of the economic bloc: the Mercosur was started by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Autist note: if you want to read more about this war, I can highly recommend reading The Road to Armageddon: Paraguay Versus the Triple Alliance, 1866-70, by Thomas L. Whigham.

Translated from this Spanish quote: “Siento decir que más de la mitad del ejército paraguayo ahora está conformado de niños de diez a catorce años de edad. Esto hizo que las batallas del 21 de diciembre y las de los días siguientes fueran realmente pavorosas y desgarradoras. Aquellos pequeños, en la mayoría de los casos completamente desnudos, regresaban del combate en grandes números, arrastrándose, mutilados de modo inconcebible. Parecía no haber lugar para ellos y entonces erraban impotentes hacia el cuartel sin proferir llanto ni gemido.”

Translated from Spanish: ¡Muero con mi Patria!

Great read this morning. Thanks for the research into that one Mara, quality post.

Those Paraguayan men returning back home after the war, actual kings.

Why Solano fought so bitterly? I read about this war before but still can not understand reasons for it. There was no other wars like that on the continent.