The role of NGO's in South America

How NGOs can disrupt national sovereignty of LatAm countries

Welcome Avatar! Today we will dive into the shady world of NGO’s in South America, particularly focusing on the Amazon and Patagonia regions of the continent. There are thousands active in the region, often employing foreigners that come to “help” local communities. Let’s look into the extended effects of all this foreign assistance for Brazil, Chile and Argentina, specifically.

The Brazilian Amazon - NGOs spread like wildfire

The Brazilian Amazon, together with parts of the Amazon forest on the Peruvian side, has historically been a hotbed for NGO activity. In 2019, it was estimated that on the Brazilian side alone, close to 16,000 NGOs were active.

Most of these foreign NGOs work in the sectors of wildlife / nature preservation, and/or protection and recognition of indigenous tribes and peoples living in the area. The Brazilian government has always been very open in terms of letting NGOs do their thing, with little oversight.

Basically adding the “NGO” label to a name enabled organizations to go about their business in the region without running into issues with the Brazilian state.

A deeper look into the 2019 wildfires

Everyone will probably remember the extensive mainstream news coverage about the Amazon wildfires in 2019. It was about the biggest news item right before the pandemic hit, with Greta hitting the Bolsonaro left and right.

It was amazing to see such a coordinated effort from literally every news outlet worldwide, covering the exact same item, while at the same time ignoring bigger forest fires in Russia, and parts of Africa. The myth of the Amazon being the “lungs of the earth” just sold better (Schellenberger explains in detail why that argument is complete nonsense).

Right before all this news came out and people like DiCaprio started crying crocodile tears for the Amazon from the comfort of their yachts and private planes, Bolsonaro had issued a decree that called for better monitoring of NGOs in the country right after he was elected into office on January 1st 2019.

Why do you think Amazon forest fires were suddenly in the news EVERYWHERE in 2019? Same time Bolsonaro started questioning the power of NGOs in the region.

“It makes you suspect there’s a hidden agenda when you see 300 NGOs in the Amazon and zero in the Northeast. Why don’t the 55 million inhabitants in the Northeast deserve an NGO, whereas the 25 million in the Amazon deserve 300?”1

— Luís Fernando Serra, Brazilian Ambassador in France in 2020

Just for the sake of fairness, let’s compare the forest hectares lost in the last couple of governments in Brazil:

Pretty stable downtrend here. Still, if you had to believe mainstream media, the Bolsonaro government was quickly burning down the complete rainforest in a matter of months.

It was still almost 3x less compared to when Lula started his first term in 2003. However, during those years (2003-2008), we never saw a similar type of outrage compared to what was thrown at the general public in 2019.

Also telling that none of the media outlets mentioned the Bolivian Amazon (or said it was connected to the Brazilian fires, which is not the case), where most of the fires started and which saw a record of hectares going up in flames.

That being said, this Mara has a profound distrust for any politician, left or right, and I am pretty sure that if given the chance, Bolsonaro wouldn’t have bothered that much with increased logging and he could’ve been using the NGOs-undermine-our-sovereignty argument to get rid of their protests. But there is more under the hood here.

The Loss of Control over parts of the Amazon to NGOs

Large forest extensions in the Brazilian and South American Amazon, since the 1970s, have been becoming the property of foreign corporations and native "associates" in the countries of the Amazon block.

The "science" of environmentalism was placed at the apex of the knowledge pyramid of social science, hierarchically in tune with regional projects. And just like in other countries, NGOs with these core values sought to impose the laws of Nature on society.

In the 70s, a new stage began. Particularly, agreements harmful to national interests threw to the ground all points of the Amazon Pact — an agreement that emerged between the countries of the Amazon bloc to stop attempts to deterritorialize the South American Amazon.

At that moment, protection areas emerged, starting with extractive reserves, continuing with "indigenous reserves", "national parks" and "state parks", in addition to "national forests".

In reality, these are strategic reserves of financial capital that go so far as to prohibit the presence of non-associated native entrepreneurs in these areas, and automatically render inoperative the validity of laws enacted by the Brazilian government that may clash with NGO interests.

These are huge strips of land, subsoil and airspace, destined for appropriation, incorporation and deterritorialization (mainly of the jungle), even though large parts of the territory had already been divided up a long time before the Amazon Pact came into force.

Already in 2007, during Lula’s first government, one Brazilian military general stated that: “Officially, NGOs are mainly aimed at defending the environment and indigenous rights, but many have hidden interests such as drug trafficking, money laundering, arms and people trafficking and even even espionage.”

Brazil is the only country in the world that does not impose restrictions on the activities of NGOs, and the legal basis for this is the Federal Constitution itself.

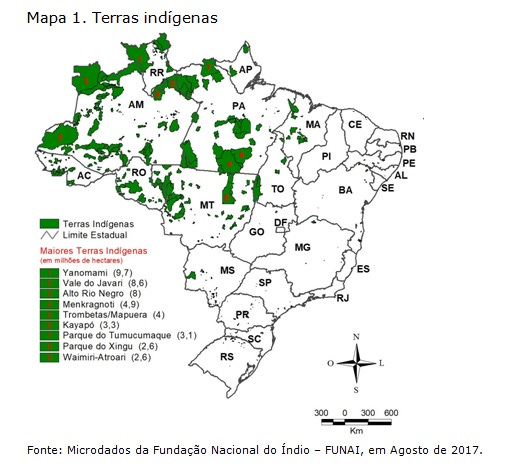

Army General Maynard Marques Santa Rosa, criticized irregularities of excessive demarcation of indigenous lands in the Amazon, and noted that some areas were the size of two Belgiums for an indigenous population of little more than seven thousand natives.

The Mapuche issue in Patagonia

Now let’s shift to Argentina and Chile, which have their own issues with similar NGOs, albeit in a completely different region: Patagonia. Just like the Amazon, Patagonia spans multiple countries, in this case the main mid-section of Argentina and Chile.

In March 2022 the new Boric government in Chile came out with an interesting map for “Wallmapu”, a proposed territory for Mapuche natives that spans most of the Patagonian region, including Argentina:

Instead of critisizing the map, government officials brushed it off as just a small recognizition of the ancestral heritage of the region and not as a threat to the sovereignty of either Chile or Argentina.

Now, when addressing the Mapuche issue in the region, I am not saying bad shit didn’t happen (as is the case for most of the history of conquest in the continent and nation building and expansion in general), but these latest efforts of trying to give more rights to certain ethnic groups by implicitly drawing new territorial lines is definitely not the right way to pay back historic dues.

On the ground, chaos ensued rather quickly after that map was released, now also on the Argentine side. But first, let’s look into the decade long conflict on the Chilean side.

Violence in “Macrozona Sur”

The violence in Macrozona Sur is an armed social and political conflict that started in 1997. It includes a series of acts of political violence that occurred in the historical region of Araucanía, in the Southern Zone of Chile, with varying degrees of intensity.

The groups related to the indigenist cause are demanding, mainly and among other measures, the return of the lands that were usurped by the State or private companies after the Occupation of Araucanía at the end of the 19th century.

Besides that they demand the autonomy of the Mapuche people or the creation of an indigenous ministry, while other more radicalized groups seek the total eradication of the Chilean State and the Catholic Church from Mapuche territory, since in their opinion such a presence would be a sign of colonialism in the region. There are multiple NGOs in the region that are pushing this secession.

Among the opposition groups are organizations of self-defense of farmers, businessmen and inhabitants of these sectors.

Only in 2022, there have been a dozen terrorist attacks by Mapuche groups on the Chilean side, and the conflict shows no sign of stopping any time soon. And all this while the leftwing Boric government is trying to do more to appease this same group, way more than previous governments have ever done.

Mapuche situation in Argentina

In Argentine Patagonia, residents live in fear of the wave of land usurpations in multiple towns. Instead of terrorist attacks, the protests in Argentina are more “benign”, and mainly attack private property in the sense that it is occupied illegally and then “claimed” for the Mapuche cause.

The people responsible are groups calling themselves Mapuche, who have nothing to do with the lands of the towns they occupy. In 2022, a series of incidents were recorded in Villa Mascardi, El Bolsón and in the vicinity of Vaca Muerta.

It takes authorities forever to clear these lands again, and frankly being a property owner in Patagonia has become a huge pain in the ass in these regions.

The Role of NGOs in Patagonia

In 2017, the Mapuches took their protest to the UN with the endorsement of a foreign NGO called “The Mapuche Nation”, which promotes a Patagonian "Kingdom" in the region, and a secession from the current countries of Argentina and Chile.

Together with this NGO, the Mapuche leaders claim that the Argentine State was founded on "the principles of racism, discrimination and xenophobia," according to the accusation read by a representative of the NGO, who is a resident in Sweden.

Auspice Stella is another NGO that encourages these denunciations against the Argentine State, includes the Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia as a "friend" page on their Facebook page. According to these folks, the "crown" in Araucania is claimed by a French prince (seems to be a bit far removed from being Mapuche, but hey, whatever).

Interestingly, Auspice Stella is an NGO with consultative status before the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations since 2013, and you can find some of their articles in the UN library here.

The NGO states that their objective is (bolding is mine):

"The purpose of our association is to support the Mapuche people of Chile and Argentina as well as other indigenous peoples of the Latin America in their fight for their human rights and to help them in order to get from the concerned countries the respect of the UN Declaration on the rights of the indigenous peoples and their struggle for land rights, for economic and cultural rights, for autonomy and self-determination."

Some notes

From what we’ve discussed above, it does seem Patagonia is a lot less sexy than the Amazon among NGOs in terms of active NGOs. That being said, there is no doubt that these organizations directly steer a course for these minority groups that advocates for separate economic areas, with minimal or no influence from the overarching nation states they are physically located in.

Notably in the Brazilian case, NGOs can pretty much do whatever, and are protected by the Brazilian constitution in doing so. Bolsonaro had to back off after the widespread media war in 2019 after he tried to change this, and it will be interesting to see if the new Lula government will change anything in terms of increased supervision, or if things will remain the same.

I expect these issues to become more important in the upcoming years, especially as the War on Resources intensifies, and the Latin American region becomes more important for the United States as we enter in a more regionalized world.

NGOs are the perfect undercover vehicle for foreign actors, Nation States or otherwise, to challenge local decision making and power structures in another country.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Wow, interesting- love how these narratives are spinner

*spinned