The United Provinces without a Kingdom

The United Kingdom's failed attempts to conquer Argentina, British influence in Argentina & BCRA creation, and the Falklands.

Welcome Avatar! The love/hate relationship between Argentina and the United Kingdom is one that spans more than two centuries by now. There have been several armed conflicts and wars between the two. At the same time much of the foreign investment that lifted Argentina to be one of the richest countries on earth around the 1900s, came from the British isles. Let’s go over some history.

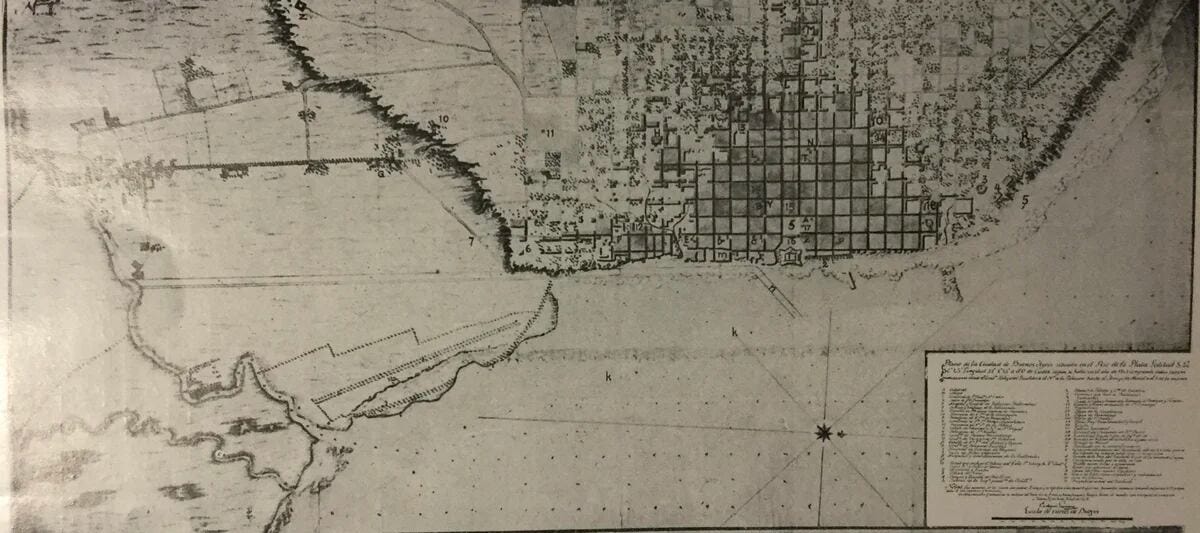

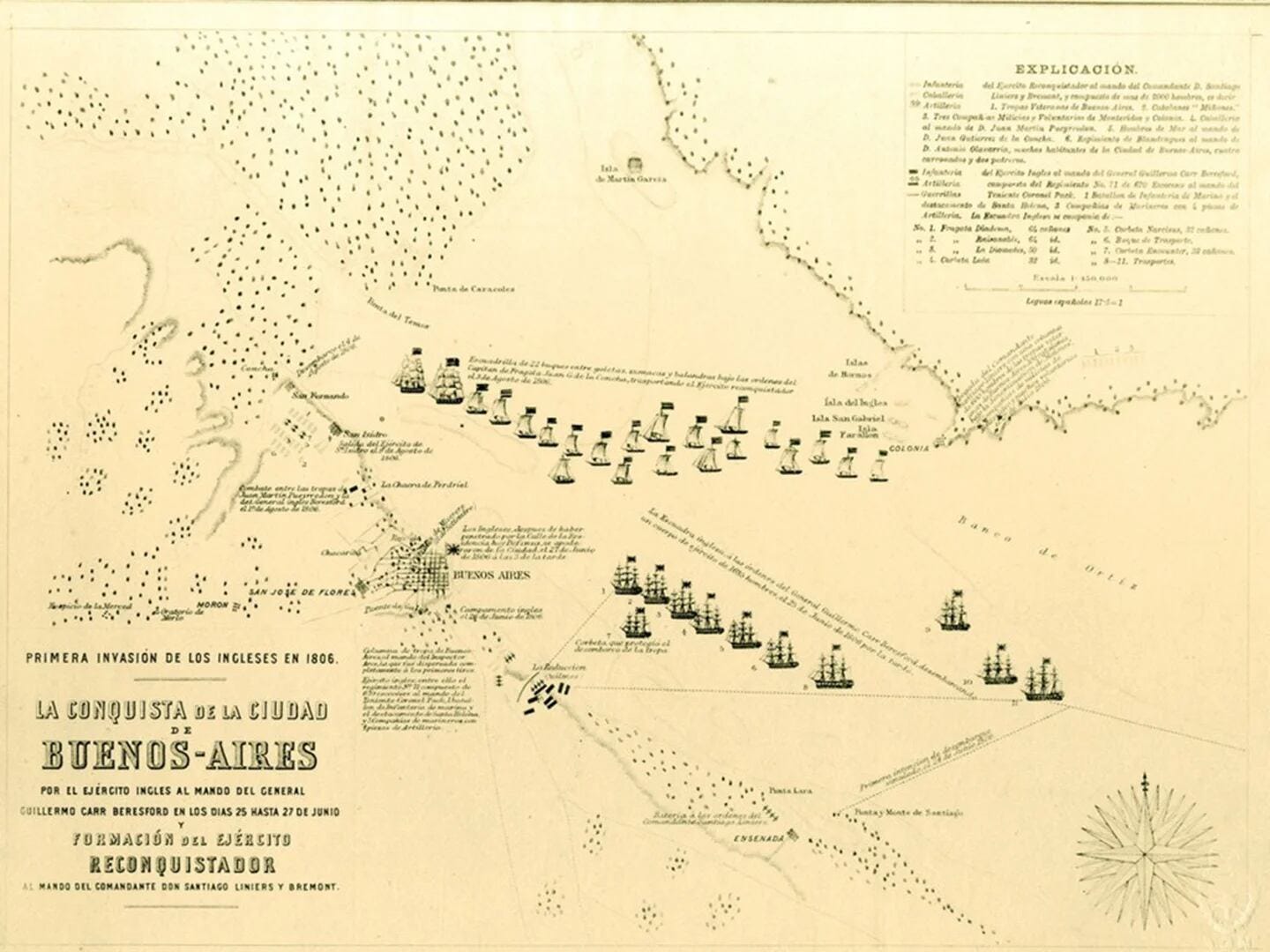

First British Invasion of Buenos Aires

In 1806 the British, under the command of General Beresford, took over the capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (modern day Buenos Aires), taking advantage of the indecisions and miscalculations of Viceroy Sobremonte.

The absence of strategy and planning made it possible for only 1,600 Englishmen to capture the city almost without firing a shot.

At dawn on Wednesday, June 25, 1806, a 32-gun frigate off the coast of Quilmes suddenly appeared on the horizon, accompanied by six transport corvettes and two English brigs.

The British invaders landed on shore that same afternoon, under torrential rain: 70 officers, 72 sergeants, 27 drummers and 1,466 soldiers.

At the time, Argentina was still part of Spanish territory, and Viceroy Rafael de Sobremonte learned of the invasion the night before while he was with his family and his future son-in-law watching the play El Si de las Niñas, which had recently premiered in Madrid.

When he found out, he left the theater and sent 300 horsemen to Quilmes to try and stop the invasion. Halfway there, the men realized that the bullets they were carrying were larger than the caliber of their cannons.

William Carr Beresford was at the head of the English troops. This 37-year-old general was the natural son of the Marquis of Waterford, which earned him the title of baron. He was an experienced commander: in the war against the independence movement in the north he had lost an eye in Nova Scotia.

On the 26th in the morning he formed his 1,635 men in a single line, with his artillery in the rear and on the sides.

The British had an encounter with the Argentine/Spanish cavalry, which they defeated easily, although they received fire from the militia infantry. The invaders came closer to the city of Buenos Aires, but didn’t cross the Riachuelo river yet.

On the night of the 26th, the viceroy left with cavalry troops towards the interior of Argentina. He had previously sent the funds of the Royal Treasury to Luján, in addition to 9 thousand ounces of his own gold. His family was waiting for him in Liniers.

Although he had had time to organize the defense, to dig trenches, place artillery and distribute soldiers and volunteers on roofs and windows, he preferred to leave the city.

At five in the afternoon the English entered the city. When Beresford appeared, the porteños presented him with a draft of the capitulation, which he didn’t even bother to read. He immediately occupied what been the viceroy's residence, inside the fort.

In less than 48 hours the British were able to conquer a town of 60,000 inhabitants without facing any major resistance, quite a feat.

Beresford was aware of his position of weakness and he ordered double the rations for the fort, so that it would be believed that he had twice as many soldiers.

Montevideo Strikes Back

In the 46 days his rule over Buenos Aires lasted, Beresford declared free trade and guaranteed property rights. He created a book where the Creoles had to swear allegiance to the British king. Many went to sign it at dusk, so as not to be seen. Others preferred to leave the city.

From Montevideo, Santiago de Liniers, together with Governor Pascual Ruiz Huidobro, prepared to retake the city of Buenos Aires.

On August 4, they disembark in the current town of Tigre and head to the city of Buenos Aires, camping in Chacarita and Corrales de Miserere, where new men join the reconquest forces.

On the 10th of that same month, they marched towards the city's old artillery park and on the 12th they managed to defeat the English troops stationed there. From there they advance towards the Plaza Mayor, cutting the British off from any military connection with their forces that were on the outskirts of the city.

The British resisted from the terraces, but the die was cast and General Beresford was forced to capitulate to Santiago de Liniers.

Second British Invasion of Buenos Aires

The attempts of the British to get a foothold in the Southern Cone were far from over: merely a year later in 1807, they tried again.

After taking Montevideo, the British troops were not able to make their way through when they tried to occupy Buenos Aires. The defending forces of the city were made up of regular troops and urban militias, made up of a population that had armed itself.

On July 7, 1807, after a gruesome fight that lasted more than 48 hours, the troops of Lieutenant General Robert Whitelocke surrendered in Buenos Aires at the ultimatum of the new Viceroy Santiago de Liniers — the same guy who fought off Bereford the year before.

British Investments in Argentina

The participation of the militias in the first Reconquista of the city and the following year (la Defensa) increased the power and popularity of the military Creole leaders and the fervor of local independence groups.

Less than 10 years after the failed British attempt to conquer Buenos Aires, Argentina declared independence from Spain in 1816 — Paraguay had declared its independence as one of the first countries in 1811.

Despite the failure of establishing a military presence, the British gradually increased their influence in Argentina by other means: foreign investment.

During the better part of the 19th century British foreign investment in Argentina increased gradually then suddenly. Around 1880 during Julio Argentino Roca’s presidencies (1880-1886 and 1898-1904), the British presence in Argentina became omnipresent: banks, railways, meat processing plants, and other British companies controlled key sectors of the Argentine economy.

For multiple years in a row, Argentina was the number 1 country for British foreign investment. These investments kickstarted the economic boom in Argentina from 1880 to 1910, and turned it into one of the richest countries (on paper) of that time.

After WWI (1914-18), British influence and investments started to decline. In the 1920s, the United States had begun to challenge the British Empire for global hegemony as a global financial and manufacturing power.

US presence in the Argentine market began to increase, resulting in a triangular trade in the 1920s in which Argentina exported raw materials to Great Britain with a commercial surplus, while importing manufactured products from the United States, with a trade deficit.

This situation generated concern in both Argentina and Great Britain, who saw a threat in the American advance since Argentine products were not purchased by the United States and exports were slowly declining due to British economic problems, tariffs in other countries, and the drop in livestock prices.

Great Britain still suffered a strong trade deficit with Argentina, which bought less and less of its industrial products.

The Creation of the BCRA & Subsequent Decline

Something had to be done to improve this symbiotic trade relationship, and not long after in 1933, the Roca-Runciman Treaty was signed between the vice president of the Argentine Republic, Julio Argentino Roca (the son of the previous President) and the British chargé d'affaires, Walter Runciman.

The treaty stated that the United Kingdom would continue to buy Argentine meat as long as its price was lower than that of other countries. In return, Argentina accepted the exemption of taxes for British products and at the same time it made the commitment not to enable refrigerators owned by national capital. Refrigeration would all be provided by British producers.

Up until that moment, Argentina did not have or need a Central Bank. It had what was called the Caja de Conversión (1899-1914 and 1927-1929), which was a precursor of a Central Bank, an independent entity in charge of issuing gold-backed banknotes and coins.

Around 1933, the new Minister of Finance, Alberto Hueyo, summoned Sir Otto Niemeyer, of the Bank of England, to prepare a new project for the creation of a central bank and another project for a Banking Law.

This was the genesis of the source of all Argentina’s future hyperinflationary woes: the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BRCA).

The BCRA was created in 1935 with the power to issue banknotes — a very bad idea, we know what happened next — and regulate interest rates. This was implemented under the direction of a board of directors with a strong composition of officials from the British Empire.

Despite all these concessions, the United Kingdom was also awarded a monopoly on transportation in Buenos Aires.

The treaty lasted three years and was renewed as the Eden-Malbrán Treaty of 1936, which gave additional concessions to Britain in return for lower freight rates on wheat.

These preferential treaties with Britain had strong political repercussions in Argentina, and they lie at the heart of the protectionist measures that would be implemented in Argentina from the first Perón government (1946) onwards.

The military dictatorship under the leadership of Edelmiro Farrell — Juan Domingo Perón was a minister in this administration before being elected democratically in 1946 —, nationalized the BCRA so it stopped being an independent entity and started to print as much as the deficit spending called for.

At the same time, more rigorous protectionist measures were put in place to make sure Argentina could start developing its own industry versus just being a resource exporter for Britain.

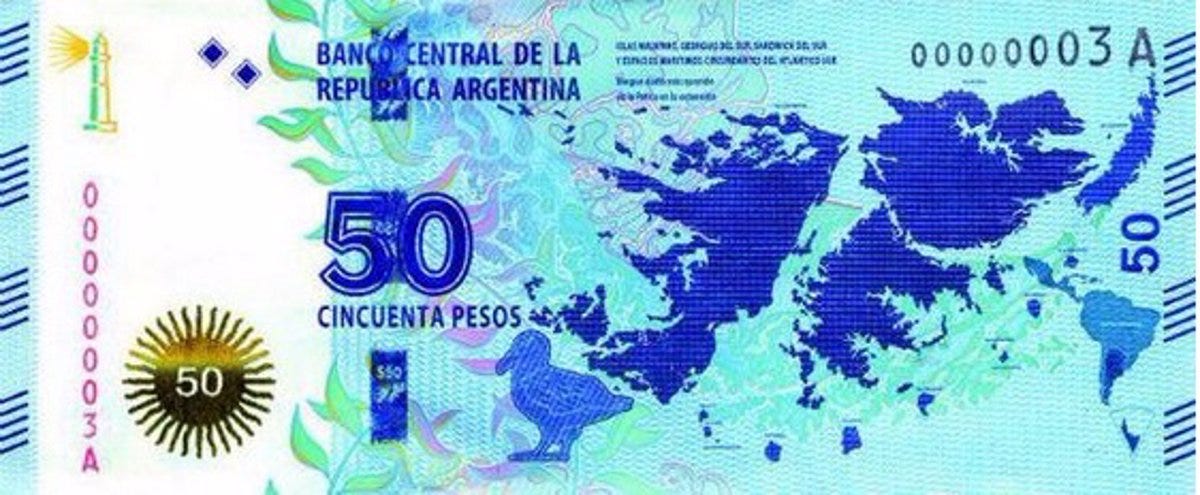

1982 - The Falklands/Malvinas War

The remaining point of conflict between Argentina and the United Kingdom is located about 500 miles off the Argentine coast: the islands at the center of a sovereignty dispute that has been going on for 190+ years.

Knowing more about the preamble of the first two British invasions and Argentina’s independence from Spain is key in the timeline and Argentina’s claims over the Falklands1, and why these are still very much alive in this day and age.

In the words of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:

On January 3, 1833, the Falklands were illegally occupied by British forces who evicted the population and the Argentine authorities legitimately established there, replacing them with British subjects who since then established restrictive measures to prevent the resettlement of Argentines.

According to the British, the islands were discovered by an English sailor in 1592 and then competed with Spain for sovereignty.

In practice, the Falklands were a no man’s islands ready for the taking and it wasn’t hard to get rid of the Argentine control that was there at the time. Finally in 1833 the United Kingdom expelled the Argentine governor and the garrison, forcibly taking control of the islands to the present day.

Argentina never abandoned its claim for sovereignty over the islands, and after taking the issue to the UN Special Committee on Decolonization, it managed to start negotiations with the United Kingdom through UN resolution 1514 of 1960. Unfortunately, negotiations went nowhere.

Fast forward to 1982.

During the military dictatorship that governed Argentina from 1976 to 1983, tensions escalated. The dictatorship felt it was losing popular support and wanted to rally the people behind a common cause. What better way to do that than to start a war?

On April 2, 1982, Argentine troops forcibly took control of the Falklands, starting the war, which concluded on June 14 with a British victory.

Argentina didn’t go down without a fight, and was able to sink multiple British ships despite having a horrendously underprepared military compared to its adversary.

Two frigates, two destroyers, a landing ship and a cargo ship were sunk by Argentine aviators. A total of 255 British soldiers and three inhabitants of the Falkland Islands died during the conflict.

Almost half of the total of 649 Argentine soldiers that died during the war correspond to the sinking of the cruiser ARA General Belgrano by a British submarine.

Autist note: A surprising detail for this Dutch-Patagonian rodent was that these planes took off from the ARA 25 de Mayo aircraft carrier, which was a ship bought from the Royal Netherlands Navy (HNLMS Karel Doorman).

Before the war, British military presence in the Falklands was almost non-existent and there was more commerce between Argentina and the islands, including frequent flights to and from the islands.

After the war, flight routes were cancelled and commerce has been minimal. For additional defense, the British military built the RAF Mount Pleasant air base, equipped with an air wing of four Eurofighter Typhoon fighters.

Aside from the sovereignty claims, significant oil reserves were discovered around the Falklands, which means it is likely that the islands will remain a source of conflict between Argentina and the UK for the foreseeable future.

Final Thoughts

The extent of British influence in Argentina is often not taken into consideration when going over recent history.

There are some conspiracy theories that overextend the British hand in Southern Cone affairs — like in the case of the Paraguay War for example —, but in the case of Argentina the impact is clear.

Street names, last names and many relics like railways and shipyards all point to Argentina’s number one foreign investor during many decades.

The fact that the BCRA was created under the influence of the Bank of England, which planted the seed for future hyperinflations, is also an interesting footnote in the country’s history.

Up to this day, the Falklands Islands claim remains one of the key issues between Great Britain and Argentina, which regularly stirs things up between the two countries.

After close to 200 years of effective British rule over the islands, of course the Kelpers (Falkland inhabitants) feel they are fully British. At the same time, Great Britain really did invade the islands and kicked the Argies out, knowing full well that the islands belong to Argentina.

In a 2013 referendum, the Kelpers were asked about were asked whether or not they supported the continuation of their status as an Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom in view of Argentina's call for negotiations on the islands' sovereignty.

Obviously, not a single Kelper felt the need to get rid of their $70,800 GDP per capita to trade it in for Argentina’s $10,636 GDP per capita. Only 3 Kelpers voted against their own interest, but 99.8% didn’t.

Milei has indicated he would be in favor of a Hong Kong type of solution, with a gradual shift to Argentine governance over time. If he is able to lift Argentina’s GDP to Falkland levels, who knows what the outcome of another referendum would be?

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Don’t want to step on anyone’s toes and this is still a very touchy subject for Argentina, but when referring to the Malvinas in English, I will use the name Falklands simply because that is the English name. When I communicate in Spanish, then I always use Malvinas. Google Translate seems to have made a change where Malvinas from Spanish to English now gets translated as Malvinas as well, but for now I will maintain Falklands just because it is the wider used term in English.

Over and above the Falklands issue, which can be debated ad nauseum, the British invasions of 1806 and 1807 have always fascinated me. Beresford was ill equipped and badly prepared and in 1807, Whitelocke was the wrong man in the right place and was a yellow coward.

The real man on the spot was Robert Crawfurd who had fought with Wellington in the Peninsula Wars and could quite easily have taken Buenos Aires if not for the cowardice of Whitelocke who refused Crawfurds strategic demands, resulting in one of the most embarrassing defeats in British military history.

This is not well known, but has been written about in several journals. Whitelocke was subsequently court marshalled as a result.

This led me to write a novel, loosely based on these facts, not least wondering in the reign of Queen Cristina, what would it be like if I, a Brit, were to be president of Argentina. Twenty years of BA living does that to you!

This was born The Last British President, my novel set in Buenos Aires where I finally become king.

Sorry for the unabashed promo and I hope you take it in good heart. I'm not president yet, but the current one is at least providing an opening, as it were.

Cheers!

Thanks @bowtiedmara. Always learning something new about Argentina from you. Great stuff as usual.