UVA: Harvesting Mortgage Grapes

How mortgage and credit could fundamentally change price dynamics for the Argentine real estate market in the medium term

Welcome Avatar! As the Milei administration is making it less interesting for banks to juice the BCRA yields by lending to the State, they are slowly starting to lend to consumers and SMEs again. One example is the UVA-denominated mortgages that have now made a comeback. We’ll go over a history of mortgage credit in Argentina and why mortgage credit in this particular point in time could have the potential to shake up property prices in the upcoming years, big time.

Markets are cyclical. Even though that sounds like a cliché, it’s also a cliché because it’s true for most markets, unless you’re dealing with scams, Ponzi schemes or perennial tulips.

In the case of real estate and the overall economy in Argentina, cyclicality is essential and the timing of investment can often determine either a boom with a great return on investment, or a bust that nukes your investment to unbearable levels.

Out of all the investments in the Argentine economy, real estate is probably one of the more stable investments, thanks to the lack of leverage in the form of mortgage bubbles, and the fact that property is priced in a more stable currency: the dollar.

Real estate in Argentina is seen as a savings vehicle to park cash, and home ownership without access to credit is actually relatively high in most provinces:

So even during a downturn like we have seen for the last decade+, property prices will only drop -30% whereas the peso, in true shitcoin fashion, does a full -99% against the dollar in the same timespan.

New buildings that are still under construction offer payment plans, that I discussed in Currency Arbitrage for Real Estate in Argentina, but used property is always paid for 100% cash, especially in the case of non-resident buyers.

Credit is basically non-existent in Argentina. That is about to change.

The Concept of UVA Mortgage loans

UVA stands for Unidad de Valor Acquisitivo, and these are real estate loans made by a bank in which the property remains as a payment guarantee or “mortgaged” until the payment of the loan is completed.

The UVA value is updated daily based on the variation of the CER (Reference Stabilization Coefficient, or Coeficiente de Estabilización de Referencia in Spanish), based on the consumer price index.

The value of the UVA in pesos is published daily on the Central Bank site.

The strategy behind the UVA consists of adjusting it to the evolution of construction costs, so the UVA is indexed to some variable that reflects the evolution of prices in the sector that generates the need to take out mortgage loans.

The concept is simple: you multiply the UVA rate by 1,000, and that gives you the m2 construction cost, which is adjusted daily by the CER-rate mentioned earlier.

May 29th 1m2 was 975.36*1,000 = $975,360 pesos / m2

May 30th 1m2 was 978.02*1,000 = $978,020 pesos / m2 (+0.27%)

The purpose pursued is to express the prices of long-term transactions in local currency (the peso), to decouple them from the variations of a foreign currency (the dollar).

The difficulty is that the income flow of potential credit takers is expressed in pesos and, therefore, does not necessarily adjust at the same speed or level as the UVA.

This is why UVAs are the perfect vehicle for shorting the peso. As we have seen with UVA mortgage lenders during Macri, their owed amount in USD got a -74% haircut from 2018 to 2023, whereas their peso instalments became harder and harder to fulfil in pesos on their local salaries. A real life example here.

This is less of a problem if you earn in foreign currency, but you have to be a resident with a credit history in Argentina to apply for an UVA mortgage.

These mortgages are denominated in UVAs and credits are returned in UVAs. So the mortgage is neither denominated in dollars nor in pesos but in UVAs, and its equivalent is paid in pesos month by month.

Autist note: At the time Macri introduced these mortgages in 2016, there were a lot of additional conditions for taking out an UVA mortgage, such as being a first time home owner (which is why the Mara family couldn’t request one, otherwise we would’ve without thinking twice. Instead we shorted the peso with CAC-instalment plan for a new construction. These are some good initial articles for more insight into the Argentine real estate market if you haven’t read them already and are thinking about buying property here. If you want to go over the full article archive related to real estate, you can do that here.

Chile: a precedent

The Argentine UVAs are actually copied from a similar system that has been a great success for decades in neighboring Chile. Whereas in Argentina UVA mortgages have come and gone depending on economic cycles and credit access, in Chile they have been a stable way to get mortgages.

In Chile, the UF (Unidad de Fomento) unit was created on January 20, 1967, when it began to operate with a quarterly value of 100 escudos that was calculated quarterly.

From 1975 onwards, this instrument began to be expressed in Chilean pesos and that same year it was updated monthly because of sudden inflationary changes. The idea was that it could work as a tool that would identify an adjustable price and for a limited period.

Chile was going through an inflationary crisis in the 1970s and faced the same challenges as Argentina today: no one saved in pesos, and pesos were converted to the next best store of value as quickly as possible. The UF instrument was created not so much for mortgage loans, but with the aim of promoting savings.

The thinking behind this mechanism was threefold: 1) without savings there is no investment; 2) capital is not offshored, and 3) capital remains pesified. So instead of saving in dollars, Chileans started saving in UFs.

In the 1980's, just 15 years after the creation of the UF, more than 90% of savers' capital were allocated in UFs, which basically meant that the economy was complety pesified.

From the 1990s onwards, Chile’s central bank started publishing the UF rate on a daily basis. Today in Chile, UFs are used for all types of credit, for investments, for contracts and even to set professional fees.

Due to the success of this index, a lot of Latin American countries copied it. In Uruguay there is the UI (Unidad Indexada), Colombia used the UPAC (Unidad de Poder Adquisitivo) up until 1998, and Mexico has the UMA (Unidad de Medida y Actualización).

The UVA Trajectory in Argentina

If we look at the last couple of decades in Argentina in terms of consumer and company credit and mortgage specifically, this pretty much trended towards zero:

And Argentina has one of the lowest mortgage percentages in Latin America, while Chile, the first country to have an indexing system like the UF, has one of the highest percentages:

If you do the rough maths on this and let’s assume Argentina could potentially end up around Chile or Panama percentages in say 30 years, that would mean a 125x increase.

This sounds promising but Argentines have a love-hate relationship with credit on macro and micro levels, and the same goes for UVA-type mortgages.

In 1980, the Central Bank ordered the indexation of mortgage loans with a rate in line with the high inflation of the time, when Martínez de Hoz's stabilization plan was already showing cracks after liberating the interest rates.

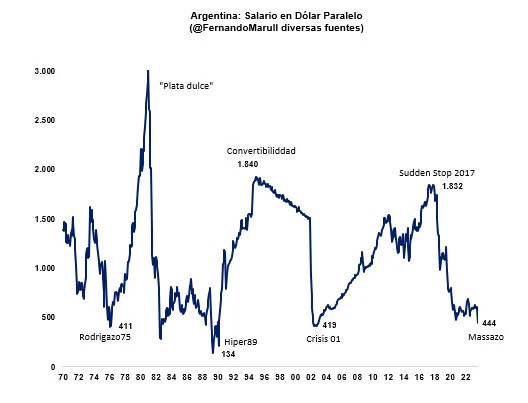

One very important detail to keep in mind is that around this time, which is also called “Plata Dulce” because salaries were so high in dollar denominated terms, Argentines were making more money —on paper— than ever before:

With high inflation AND historically high salaries in Argentina, taking on indexed debt was a time bomb waiting to happen. And it went off.

The BCRA notice called circular 1050 was a poorly calculated price release, which surprised thousands of mortgage debtors at a particularly difficult time for the local economy. It adjusted the mortgage rates at market price (very high inflation), in a stagnating economy with super high salaries in dollar terms.

Just look at the graph above and see what happened right after: the average salary nuked from $3k usd/mo to $400/mo in the span of just a few month. People who took out a mortgage during that peak of high salaries got absolutely sandwiched between not being able to pay their mortgage and insane rate increases fuelled by high inflation.

A lot of people lost their homes and worse: they still owed debt after auctioning off their homes. Because even by selling the house they did not cancel the commitments made with the banks.

A similar, but less dramatic version of this story happened during Macri’s term (2015-2019), when he opened up the economy, paid off creditors and access to credit became easier:

You can see what happened next: average salaries in dollar terms dropped from $1800/mo to $450/mo due to inflation and printing the peso into oblivion, and people couldn’t service their mortgages anymore or are at a point that they will never pay it off in their lifetime based on their current salaries.

In dollar terms, it was a steal, in pesos, they got crushed. Less dramatic compared to the 1980s, but a similar trend with high salaries destined to go down.

Why would this time under Milei be any different? Well, let’s look at the salary graph again. Salaries are currently at all time lows. That means that in a less inflationary environment — which the current administration will likely pull off —, salaries will go back up to the mean, which is a lot higher (2-2.5x historically).

That means that taking on an UVA-mortgage now is vastly different and probably less risky than when doing so with historically high salaries. Which means that UVA-mortgages have a lot more room for growth versus under Macri.

If the current trend continues where the economic team of Caputo-Bausili keep lowering rates, banks will increasingly be forced to lend money to consumers versus the BCRA.

How much could m2 prices increase for property in Buenos Aires? It depends on a lot of factors, but in previous scenarios discussed above which were far from ideal, prices increased by 58% (1980) and 33% (2015-2018).

When looking at the average m2 price in the city of Buenos Aires, what went down for six years in a row, is bound to make a comeback.

Even more so under more favorable market conditions with additional credit.

Final Thoughts

Construction costs are already nearing ATHs, and those will start reflecting in the sales prices of property soon:

The UVA mortgages combined with the cyclical low point with regards to salaries and the overall economy, are a good indicator that these mortgages will become more popular, and that credit will be more readily available especially if interest rates drop even more and Argentina’s economy starts picking up again after the current recession.

Once the realization kicks in for locals that their salaries are at all time lows (300-500 USD/month), confidence in being able to take out an UVA-mortgage as their salaries return to the mean ($800-$1,250/mo) will be a matter of when, not if, especially in a low inflation environment.

If the mortgage market picks up in Argentina as it has during previous cycles, we could see property prices in A+ neighborhoods like Belgrano, Palermo, Recoleta, Colegiales, Chacarita and Puerto Madero move up quite significantly.

Other neighborhoods might be more of a gamble in the sense that you might get a higher return on the initial investment, but there’s no STR guarantees so these would serve more as long term rentals with a lower yield.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

Excellent analysis as usual. Real estate prices are going to skyrocket in the next several years.

Excellent write-up, Mara! Adds useful details to my research on IRSA.