Argentina's Century-Long Decline

How and why Argentina went from being one of the richest countries to where we are now (and how stats do not always tell the whole story).

Welcome Avatar! Argentina’s GDP graph cratering from the heights of one of the wealthiest nations on earth is one for the history books, and it has become a famous case study at this point of what not to do if a country likes economic growth and prosperity. Today we will go over some of the causes of the century long decline, and reasons why Argentina never fully goes bust compared to countries like Venezuela or Cuba.

"There are four kinds of countries in the world: developed countries, undeveloped countries, Japan and Argentina"

— Simon Kuznets

At the end of the 19th century, Argentina was the richest country in the world. As much of a fairytale it may seem by now, Argentina was the most powerful country on the planet at that time.

What made Argentina so successful in the first place?

After the May Revolution in 1810 and Independence in 1816, Argentina could not easily find a model of prosperity.

At the end of government of Juan Manuel de Rosas (1852), the country adopted the draft Constitution of Juan Bautista Alberdi (1853/60), clearly liberal in orientation, drawing inspiration from the United States Constitution.

The new political and legal framework was pro-immigration, defended free enterprise, kept the State away from productive development and limited itself to offering the appropriate legal framework within a rule of law.

The results regarding attracting immigrants, stimulating growth through and economic development little state interference are clear: it turned Argentina into an economic powerhouse, not only in the region, but worldwide.

Argentina was a successful example of migrant inclusion: Italians, Spaniards, Jews, Portuguese, Germans, and Paraguayans made up the largest immigrant group. Several of these arrived with capital to invest, which had a favorable impact on the country.

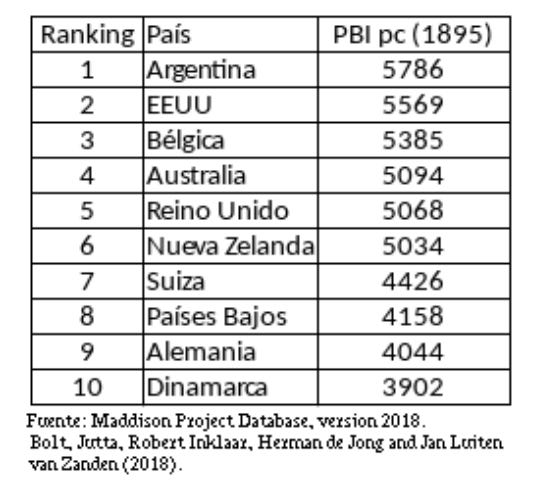

In economic terms, Argentina ranked above the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom and the usual powers. By the year 1895 Argentina had a GDP per capita of $5,786 dollars, followed by the United States and Belgium in third place.

Between 1870 and 1920 more than 70% of foreign investment in the region went to Argentina.

At that time, Argentina had one of the most liberal economies on the planet. This allowed the Argentines to begin working in the fields and exporting raw materials to Great Britain, which for years was their main trading partner.

President Julio Argentino Roca was perhaps the greatest architect of Argentine economic growth. In his first term there was an expansion of land, work and capital, due to immigration that was well used, with the granting of available land. At that time, sheep's wool was one of the main export products, and little by little Argentine meat gained space and an enormous reputation in international markets.

Under Roca's mandate, the so-called Conquest of the desert took place, which annexed millions of hectares to Argentine control. These would later be used to strengthen and increase production and the country's economy.

Autist note: you can read more about this conquest in the article below. Without this additional land grabbing, Chile would most likely have owned most of southern Argentina:

During that period, the economy of the Pampa increase tenfold, together with exponential increases in meat and grain production.

Argentina, selling its products abroad, became the richest country on the planet. Such was the case that by then the Argentine GDP per capita was three times higher than that of the rest of the countries in an underdeveloped region.

After a few years with some economic setbacks under the administration of Roca's successor, Miguel Juárez, who fell into the habit of enormous public spending, the former president with the last name "Argentino" returned to the presidency after protests over the impact on the economy.

Through privatizations, exports and incentives for production and agriculture, the Argentine economy got back on track. A couple of years later it effectively became the richest country in the world.

Argentina was also a successful example of migrant inclusion: Italians, Jews, Portuguese, Germans, Spanish and Guarani made up the largest immigrant group. Several of these arrived with capital to invest, which had a favorable impact on the country. Between 1870 and 1920 more than 70% of foreign investment in the region came to Argentina.

The process of industrialization was just getting started at the turn of the century, and by 1914 it represented only 16% of GDP. Argentina was still mainly rich thanks to its resources and agricultural exports.

The Long Crash

One important side note with the whole GDP per capita statistic from the 1900s is that even though on paper this looks fantastic, on the ground this looked a bit different: by that time wealth was still highly concentrated among the exporting estancieros and the ruling class.

This is important to keep in mind to understand why a movement like Peronism could become so popular in Argentina in the first place.

But still, a rising tide lifts all boats, and there are no shortcuts even though some politicians would like their voters to believe that this is possible.

So what went wrong? The answer is simple: exacerbated protectionism, accompanied by a good dose of public spending, nationalization and, at the start of the 21st Century, socialism.

As only a few years are needed to reap good results, a virtuous process can also be ruined in a short time.

Argentina suffered its first military coup in 1930, after three constitutional presidencies that were the product of free and democratic elections.

The institutional damage worsened when the Supreme Court of that time endorsed the figure of the de facto government that broke with the incipient democracy.

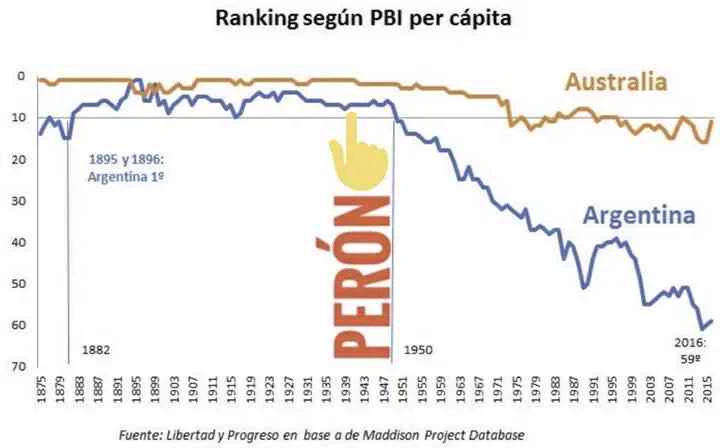

A new military uprising in 1945 ended with the arrival of Juan Domingo Perón the following year as president — he had been part of the de facto government as Minister of War during WWII.

Learn more about a darker part of Perón’s legacy here:

Lieutenant Colonel Perón rose to popularity by serving as Secretary of Labor and Welfare, making ties with the country's socialist and communist workers' unions, and achieving negotiations that "favored" the employees.

Perón's popularity grew until he became vice president, and then he was elected president of Argentina.

It was during the first Perón presidency that the original Alberdi Constitution was changed, which went from a liberal model to ignoring the inviolability of private property, within the framework of a fascism inspired by the Italian model of Benito Mussolini.

After the coup that overthrew Perón in 1955, the Constitution that was put into effect was already a hybrid between the Constitution of Alberdi and Perón. Although there was the liberal spirit of Articles 14 and 19, Article 14 bis appeared with "social rights", a legacy of Peronism (emphasis added):

“The State will grant the benefits of social security, which will be integral and inalienable.

In particular, the law will establish: compulsory social security, which will be in charge of national or provincial entities with financial and economic autonomy, administered by the interested parties with the participation of the State, without the possibility of overlapping contributions; retirement and mobile pensions; comprehensive protection of the family; the defense of family property; economic family compensation and access to decent housing.”Article 14 bis from the current Constitution1

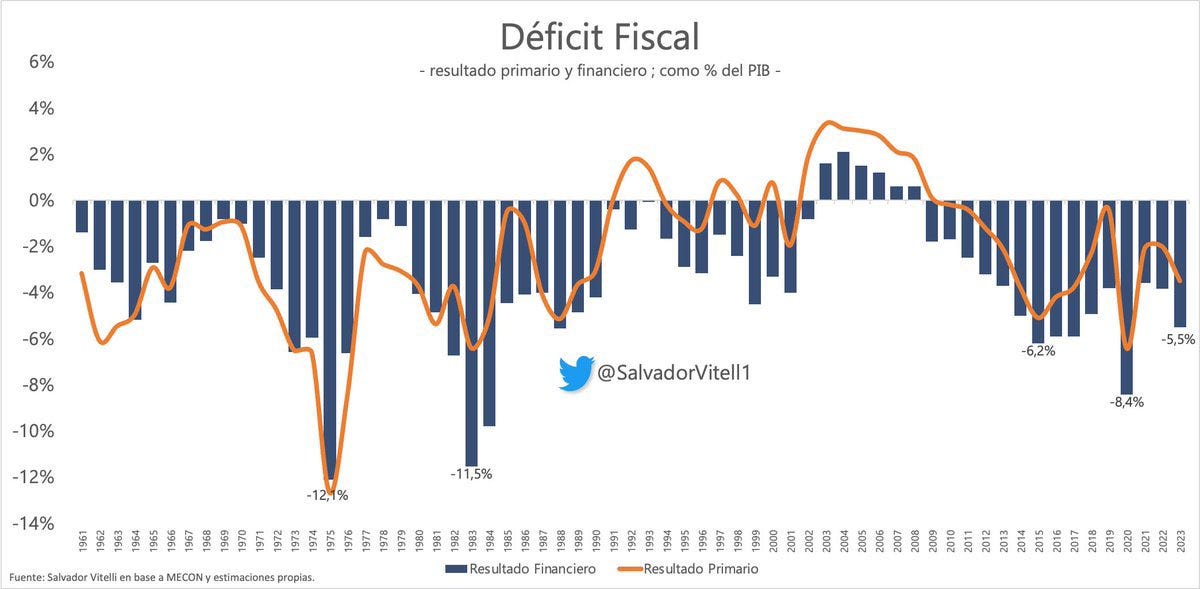

From that moment on, Argentina was plagued by statism, deficit crises, inflation, and insufficient patches that became solutions that were as precarious as they were counterproductive in the long term.

The Long Way Down

The first Peronist government was characterized by maintaining exacerbated public spending that was justified by “redistributing income to the poorest” and starting to intervene forcefully in the economy.

Juan Domingo Perón began to impose heavy tariffs on trade and the four fundamental principles of his doctrine were: 1) the domestic market, 2) economic nationalism, 3) preponderant role of the State and 4) central role of national industries.

As you can see from these 4 points, they are the same failed premises that keep Argentina in the place it is today.

Perón introduced all the ingredients that keep the perpetual doomloop of economic crashes every 10-15 years in place: uncontrolled printing of banknotes, high public spending including nationalizations, excessive inflation, high protectionism and an excess of regulations, all in exchange for a “redistribution of income”.

The results are always the same: Argentines end up becoming poorer, but at least they have a political father figure that is “fighting for their rights”.

In Doug Casey on the World’s First Anarcho-Capitalist President, Casey gives a perfect synthesis of “Peronism” (emphasis added):

Peron was an overt fan of Mussolini and fascism. Fascism—a word coined by Mussolini—is defined as the complete subordination of corporations and business to the State.

After WW2, the word “fascism” was a no-no, so the system was rechristened “Peronism” in Argentina. It’s not a consistent philosophy; it has many mutations. It’s all about businessmen and politicians using each other, through the State, to get rich. The lower classes are made dependent, and the middle class is impoverished.

Fascism has little to do with militarism and jackboots; it’s an economic system. Almost every country in the world is fascist today—including the US, the EU, China, and Russia.

I will refer to these businessmen and politicians using the State apparatus to get rich as the Cantillionaire Class for the remainder of this article.

The Cantillionaire Class

It’s incredible that someone with a Louis Vutton bag claiming to be ‘standing up for the poor’ and ‘against the interest’s of vile entrepreneurs’ can be taken seriously.

But, in Argentina, the Cantillionaire Class has tricked the masses (at least up until now) into believing their every word.

Argentina has been run for decades by this oligarchy that includes populist politicians, trade union leaders, crony capitalists, and federal judges.

These groups have colluded to create a system of rent-seeking corporatism, where power and economic returns are determined through political bargaining rather than through the free market.

This system has led to an excessive regulation of the economy, which stifles competition and innovation. Protectionist policies exist to benefit the cronies at the expense of consumers and businesses, and Argentina’s inflexible labor laws make it difficult for businesses to hire and fire workers.

Economically, the government has been unable to control its spending, which has led to chronic deficits and inflation. Inflation is a form of taxation that disproportionately hurts the poor and middle class. It also makes it difficult for businesses to plan for the future and invest in the economy.

The result of this political and economic system has been poor economic performance. Since 1960, Argentina has had 22 years of negative GDP growth, more than any other country in the world. This has led to high levels of poverty and inequality.

However, growth has not been negative for the Cantillionaires. The oligarchy has used its power to enrich itself at the expense of the public, as Casey also explains in the same article:

If we divide Argentine society into a ruling, a lower, and a middle class, it’s clear that for the last 80 years, the ruling class has used welfare schemes and lies to get the lower classes to vote against their own interests.

The middle class has paid for it with immense taxes and regulations. Inflation has basically destroyed the lower and middle classes; high inflation has made it impossible for them to save and build capital.

Boom & Bust Cycles

These populist measures do not mean there is no wealth creation since the decline.

Argentina is so rich in human capital and resources that even though it is plucked dry by the Cantillionaire Class, there are still remarkable phases of growth. This kind of growth has usually been temporary, eventually ending in another crisis.

As you can see in the graph above with the fiscal deficits, fiscal surplus usually ensues after a big crisis. In 2003 this was further propelled thanks to the boom in commodities, which ended up boosting Argentina’s economy even more.

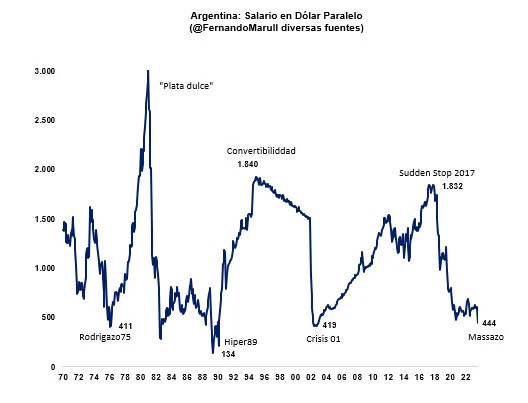

To get a grasp of how the monetary madness of the Cantillionaire Class works out for the average Argentine citizen/resident, let’s look at the average salary in dollars in the last 50 years before and after each crash:

In 1975 salaries dropped from a peak of $1,600 to $400, in 1982 from $3,000 to $200, in 1989 from $800 to $134, in 2001 from $1,800 to $400, and in 2023 from $1,800 to $444.

This is one the things for investors to understand: if there are no structural changes in Argentina, nothing is a long term hold. So long as that is the case, Argentina is a trade, not an investment. You can trade these booms and busts and make some amazing returns if you hop off in time.

But after every crash, there is less fuel left in the tank. People get tired, and the best and brightest tend to leave the country in search for better opportunities.

This upcoming crash which has been a few years in the making, looks like it will be one of the biggest. There is no capital left in the Central Bank, Argentina is highly indebted and the currency will likely not survive without slashing zeros or full replacement.

The Solution?

The solution for the future, even if it is paradoxical, is in the history books. The only difference in relation to the boom that the founding Argentina experienced with which it may come in the future, is that technology and globalization could make it much easier, faster, simpler and exponential.

The reason why Argentina still hasn’t collapsed completely like Venezuela or Cuba, is due to the fact that its economy and resources are very diversified: in the other two countries it only took the nationalization of one single industry (oil and sugar, respectively), to burn it all to the ground.

In Argentina the agonizing process of decay can seemingly last forever, and even show periods of growth in the middle. Relatively, there is so much wealth in Argentina that just by dropping a few breadcrumbs, the Cantillionaire Class could secure a new generation of voters.

Or at least up until now.

With the upcoming elections it looks like Argentines want to vote for a change, but we will have to see if that change ends up converting into a cultural change on many different levels of government and society as a whole.

It will not be an overnight thing to roll back almost a century of failed economic policies, but the seed for change was planted at the primary elections las month.

What is almost a certainty at this point is that we will first experience another loud bust, before potentially seeing a new boom. And if that boom does come, let’s see if it sticks this time.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Translated from Spanish: “El Estado otorgará los beneficios de la seguridad social, que tendrá carácter de integral e irrenunciable. En especial, la ley establecerá: el seguro social obligatorio, que estará a cargo de entidades nacionales o provinciales con autonomía financiera y económica, administradas por los interesados con participación del Estado, sin que pueda existir superposición de aportes; jubilaciones y pensiones móviles; la protección integral de la familia; la defensa del bien de familia; la compensación económica familiar y el acceso a una vivienda digna.” — full CN text here.

Excellent post

A great read Mara! All seems very obvious what went wrong from an outside point of view. That Aus vs Arg GDP chart with the timing of Perón should be posted out to the millions.

Interesting point regarding the stability in Argentina over countries like Venezuela & Cuba. Makes perfect sense.

Thanks again, I learn a lot from your work.