Peronist Ping Pong

How Peronism ebbs and flows throughout Argentina's recent history

Welcome Avatar! Investors and libertarians worldwide are looking at Argentina with renewed interest after Milei got elected, hoping this will finally be the nail in the coffin for decades of primarily Peronist rule. Will it though? A deep dive into the ebbs and flows of the movement throughout Argentina's recent history.

The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist.

— The Usual Suspects (1995)

The same goes for Peronism.

In order to understand the roots of this political current which, like a true chameleon, can encapsulate practically any ideology, we have to start with the man who gave the movement its name: Juan Domingo Perón.

In Doug Casey on the World’s First Anarcho-Capitalist President, Casey gives a perfect synthesis of “Peronism”:

After WW2, the word “fascism” was a no-no, so the system was rechristened “Peronism” in Argentina. It’s not a consistent philosophy; it has many mutations. It’s all about businessmen and politicians using each other, through the State, to get rich. The lower classes are made dependent, and the middle class is impoverished.

Let’s start at the birth of the movement.

The First Two Peronist Governments (1946-1955)

As we described in Peronism and Nazi Germany Part 1 and Part 2, Perón’s rise to power started in the 1943 Military Coup government he was a part of.

Perón participated in the coup as an active military member and started in this administration as an aide to Secretary of War, and later headed the Department of Labor.

Heavily influenced by Mussolini’s politics after spending a few months in Italy before World War II broke out, Perón was convinced that fascism was the best system of government to balance the relationship between capital and labor and thought:

“From Germany I returned to Italy and dedicated myself to studying the subject of Fascism. My knowledge of Italian allowed me to penetrate, I would say deeply, into the foundations of the system, and that is how I discovered something that from a social point of view was very interesting for me. Italian Fascism brought popular organizations to an effective participation in national life, from which the people had always been separated.”

— Juan Domingo Perón

Right after the war, Perón ran for president in 1946 and won the elections. This was the start of a political current that would mark Argentina’s politics up to this day.

Perón’s Use of the State Apparatus

Not many Argentines know how political repression was handled during the first two governments of Juan Domingo Perón. It is clear that the young militants of the 1970s, who brought him back to the country, were unaware of it or did not believe many of the stories told by their elders.

Already in the second year of his first presidency, in 1947, the opposition had been cut off from most communication channels. Perón came to the presidency in 1946 with the support of very few media outlets. He was supported only by one afternoon newspaper, La Época.

At the start of 1946, during the regime initiated by the dictatorship of 1943, an Executive Order was issued that would later prove crucial for Perón to muzzle the journalistic opposition: an authorization to the Executive Branch to provide paper for newspapers.

The management of paper for printing, with different tricks, was the start of the history of violations of freedom of the press in Argentina. The annual distribution of this raw material, fundamental to written journalism, was done through other decrees.

It was an obvious mechanism of control of the press: through official norms, Perón could directly determine the number of pages with which each newspaper should be published.

The closure of newspapers and periodicals by the “Visca Commission”, the closure of printing presses “for disturbing noise”, the state monopoly on radio and a gigantic apparatus of official propaganda, left no legal margins for the opposition to express itself freely.

In 1951, Perón decided to expropriate newspaper La Prensa, thereby obtaining Argentina's most popular daily. Its pages gave a lot of space to classified ads, essential when looking for a job.

At the time of its confiscation, La Prensa sold just over four hundred thousand copies on weekdays and half a million on Sundays. The Argentine population at that time was less than 20 million inhabitants.

A labor dispute was the perfect excuse for the takeover.

Perón also created a Peronist blacklist of all artists and celebrities who were restricted from exercising their vocation for being ideological opponents of Perón's first government (1946 - 1955), especially during his first term, with the active participation of the renowned Eva Perón.

Propaganda & Brainwashing

After taking control of much of the media apparatus, silencing dissident voices, and making sure the press did not have too much freedom, Perón went full Kim Jung-Il and decided to institutionalize the cult of personality around himself and his wife Eva Perón.

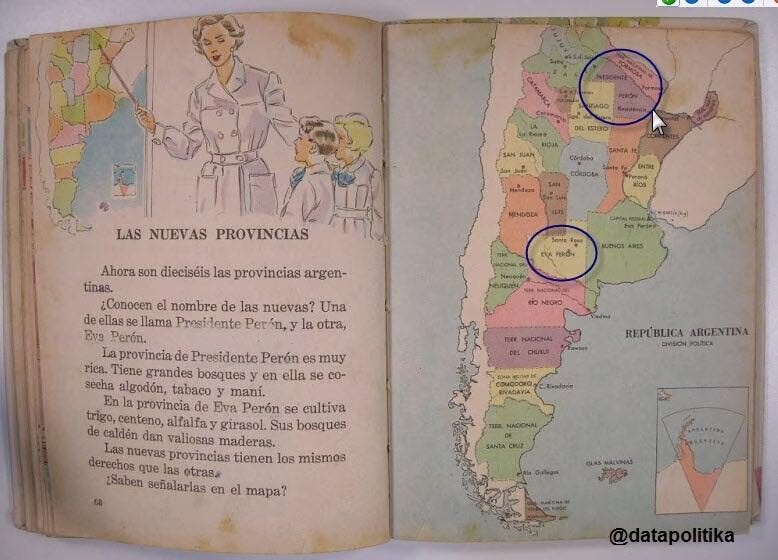

In true DPRK style, mandatory school books were printed highlighting the greatness of his leadership and the unselfish kindness of Evita who watched out for her descamisados (“shirtless” workers) and poor children who couldn’t afford clothes, while she rattled with her latest jewellery as she handed them over.

In 1951, Perón went one step further and decided to rename two provinces: Chaco was converted into “Presidente Perón” and the province of La Pampa was now to be called “Eva Perón”.

This overdose of nepotism and propaganda was starting to rub the opposition the wrong way, and anti-Peronism started to grow as a movement within the higher ranks of the military.

Crackdowns and Anti-Peronism

Despite his undisputed leadership in children’s school books, Juan Domingo Perón lived in a constant state of paranoia in the midst of an obsessive microclimate of obsequiousness where the idea of a new uprising reigned.

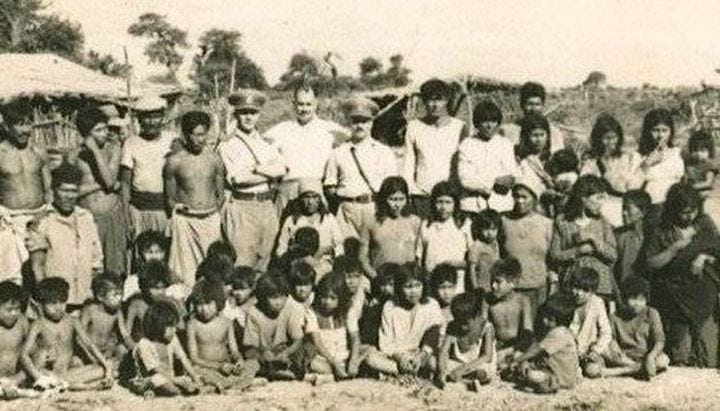

In 1947, during the first Peronist government, the Gendarmerie killed between 500 and 750 men and women of the Pilagá aboriginal people in the Formosa province. They did so with air support of the Air Force, for fear of an “indigenous attack”.

More than seventy years later the courts classified the action as genocide, although those responsible were never convicted.

This story deserves a separate article, but it is worth mentioning that this happened just after little over a year into the first Perón presidency. When reading the background it was pretty clear that this indigenous group never posed a real threat to Formosa’s provincial powers or Perón’s national government for that matter.

A real attempted coup d'état occurred in in September 1951, when members of the Army, Navy, and Air Force attempted to overthrow his government. Another coup was predicted at any moment.

Finally, a few years later the uprising that would mark the end of his first two terms would arrive.

1955: La Revolución Libertadora

No matter how nefarious Peronism can be, sometimes the wish to get rid of it can lead to taking even more disastrous measures, and there are multiple examples of that throughout Argentina’s history.

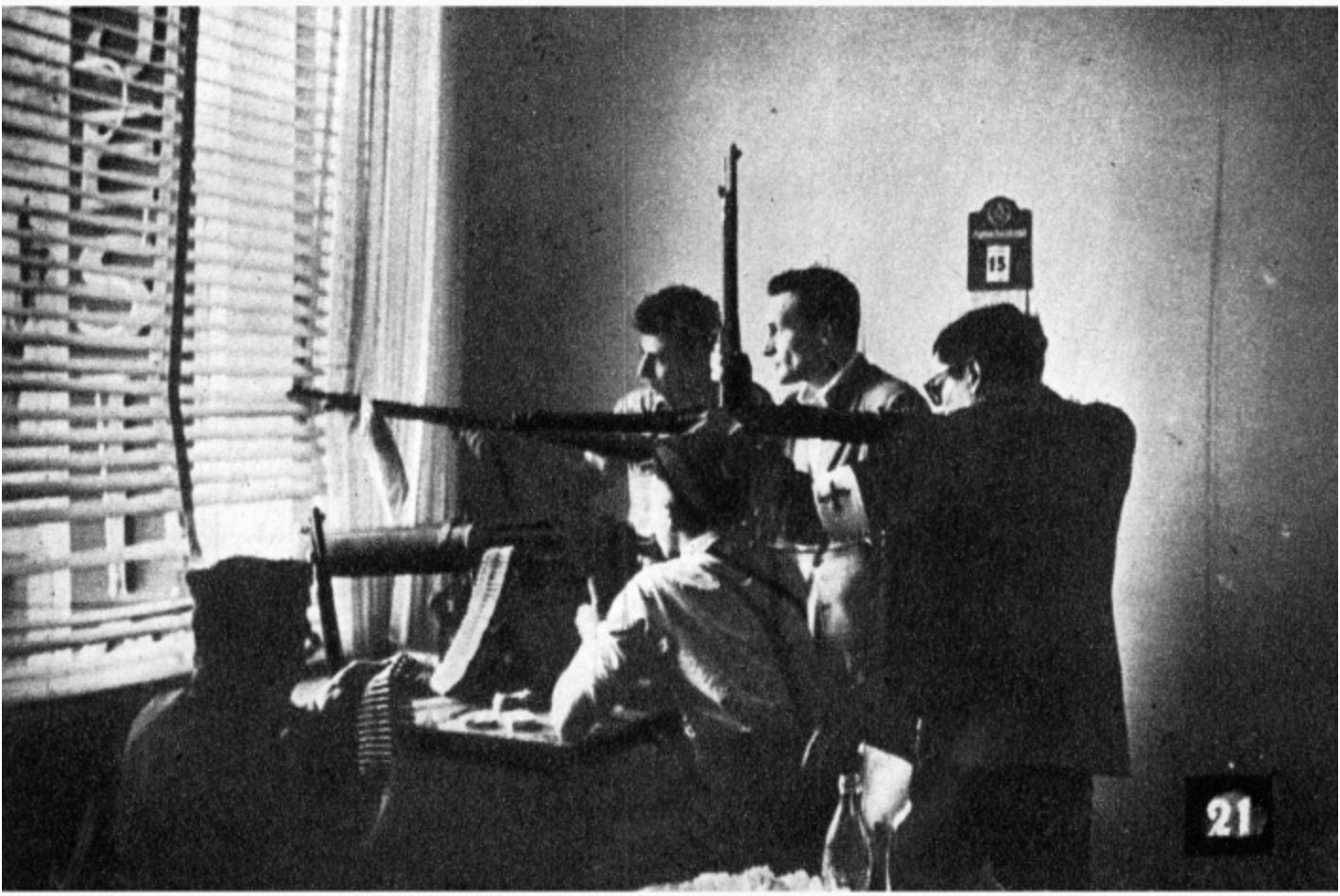

The 1955 bombing of the Casa Rosada and the Plaza de Mayo is one them. It was a plan by the Navy inspired by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Various naval and Air Force bases were taken over by coup plotters and the Plaza de Mayo and its surroundings were bombed for five hours. They intended to take over the Casa Rosada with “civilian commandos” and create a “democratic” government afterwards, without Perón.

Naval aviation would bomb the Casa Rosada at the time when Perón was meeting his “general staff,” the men with whom he shared government decisions.

He met with them every other week, on Wednesdays at ten in the morning. At that time the bombing would begin. It should have lasted only three minutes.

After Perón was informed that the airports of Ezeiza and Punta Indio were taken by army troops planning a coup, he took refuge in the Army Ministry between 9 and 10 in the morning after learning of the planned bombing.

Perón did not order the evacuation of the Casa Rosada. At that time, around four hundred people, including officials, employees and members of the public, remained in the Government House.

Many people who were passing through the Plaza de Mayo and its surroundings were also at risk.

Why did the government not warn, or prohibit movement, or close access to the main square?

These questions remain unanswered, but no one was warned and the attack was carried out a few hours later than originally planned, with typical Argentine punctuality.

After heavy urban fighting, the besieged rebels finally opted for handing over the Ministry of the Navy to the Army units posted outside.

In total, more than 10 tonnes of ordnance were dropped, killing between 150 and 364 people, mostly civilians, and injuring over 800. Some victims could not be identified. The number of identified bodies was put at 308, including six children, making it the deadliest terrorist attack in Argentine history.

After the initially failed coup, Perón gave his famous Cinco por uno speech in which he said:

We must respond to violence with greater violence (...) The motto for every Peronist, whether isolated or within an organization, is to respond to a violent action with another more violent one. And when one of ours perishes, five of theirs will perish.

These words caused great repulsion among those who did not belong to the Peronist ideology.

Just two weeks later, on September 16 1955, the operation to overthrow Perón had the necessary support of the main opposition political parties and the Church, sheltering numerous civilian commandos who acted alongside rebel soldiers.

Finally, after a week of bloody fighting, the coup was successful, with a death toll of more than 150.

The 1970s Comeback

Perón was forced to flee to dictator Franco’s Spain after the military coup of the Revolución Libertadora, and Peronism as a political current would remain proscribed from elections until 1973.

Those who had thought that Peronism was done for during those 18 years of proscription, were in for a nasty surprise.

Perón returned as a candidate in democracy and won the 1973 elections without much effort. But his presidency up to his death in 1974 would be short, and turbulent.

The 1970s would be one of the most chaotic decades in Argentine history before and during the Military Junta overthrew the government of Perón’s wife Isabel in 1976, who was Vice President and took over after her husband died.

For a full breakdown, Different Types of Condors gives a comprehensive overview of that era:

This was the second time that Peronism was “gone”, and some thought that because Perón himself was no longer alive, the movement would die with its creator.

Menemism: “Neoliberal” Peronism

When the Military Junta ended in 1983 and democracy returned to Argentina, the country eventually spiralled into hyperinflation under president Ricardo Alfonsín after years of suppressed dollar rates and an artificially high peso.

Autist note: in this article the mechanics are explained in detail, together with an analysis on why the same mechanics could become a problem for the current government:

After reaching a high point of 5,000% inflation and an economy in shambles, Alfonsín, the first democratically elected president after 7 years of brutal dictatorship, was not able to end his mandate and called for early elections in 1989.

It was time for Peronism to make a comeback, but this time in a completely different costume, or at least, so it seemed at the time: a market-friendly, “neoliberal” Peronist administration under the presidency of Carlos Menem.

In practice, despite very good deregulation measures for the overall economy, corruption ran rampant in Menem’s administration and many of the privatizations were done with insiders for pennies on the dollar, making huge profits for those involved — in a way similar to how Russia privatized its State industries after the USSR fell.

By doing so Menem was honoring his Peronist roots but in reverse: he made sure the State’s cronies could personally benefit from undoing the massive State Apparatus created by Peronism and kept in place (or worsened) over time.

This is one of the reasons why critics regard Milei’s privatization efforts with a certain suspicion — Will It Fly discusses this in depth.

Due to printing more pesos than those that were actually backed by dollars in reserves to fund deficits, Menem’s presidency ended with a severe crisis that culminated right after he left office.

Kirchnerism: Socialist Peronism

During the Corralito crisis in 2001, Argentines could not take out their bank account savings, which received a 3:1 haircut from the subsequent devaluation.

Before this during Menem’s two presidencies, 1 peso was pegged to 1 dollar, so imagine how much trust Argentines had left in the banking system after seeing their savings cut by two thirds.

Five presidents passed the baton in rapid succession in little over a week, probably a world record.

When the dust settled, President number 5 in that list Eduardo Duhalde, did the dirty work of implementing austerity measures and leaving a better starting point for the man that would transform the Peronist cloak once again: Néstor Kirchner.

With Néstor Kirchner and the subsequent mandates of his wife Cristina, a new Peronist era was born: kirchnerismo.

They still referred to their movement as Peronist, but technically kirchnerism embodies many of the Marxist elements that Perón fought against in the early 1970s.

Kirchnerism did a 180 on Menem’s open for business policies, and started implementing more protectionist measures to see if they could start up national industries etc.

In the process, many essential companies were renationalized, like YPF, Aerolíneas Argentinas and a few more.

One thing they did share with Perón and Menem was how these nationalizations took place: many of the cronies close to the pie got to take a bite. In that sense it was undeniably “true Peronism”.

Cult of Personality

As you will understand by now, Peronism morphs into whatever the current situation requires to win the elections.

The important question is: will a charismatic figure be able to call himself a Peronist and win them, whatever his political beliefs may be.

Argentines love to convert mortals into mythical figures and have done so over and over throughout the last century: Gardel, Perón, Evita, Maradona, and today Messi, are all “bigger than life”.

The same is happening with Javier Milei: his followers also put him on a libertarian pedestal and he is elevated to Saint-like levels, Argentina’s saviour.

If it is not clear by now, this populist popularity is the only way to win elections in Argentina.

Autist note: this “bigger than life” mystification is taken quite seriously and is upheld way after some of these “saviors” are dead and buried. Read some of the most bizarre stories here:

If that conviction is not present, like what happened during Mauricio Macri’s presidency for example, it becomes very hard to count on the goodwill of the majority. Voters swing to the extremes, and this is why Milei better not shift to gradualism or start “taking it easy”.

The middle road is the road that leads directly to the opposing politician that gives the biggest vocal and charismatic pushback against who is currently governing.

If there’s too much silence from the current administration, that opposition will start to gain momentum.

In a recent poll, 80% of young people believe that the situation in the country is bad or average, but 64.5% would vote for Milei again. The younger generations and especially high school kids are still in favor of Milei and his policies. It is essential to for Milei to retain these votes.

Final Thoughts: Present Day & Milei

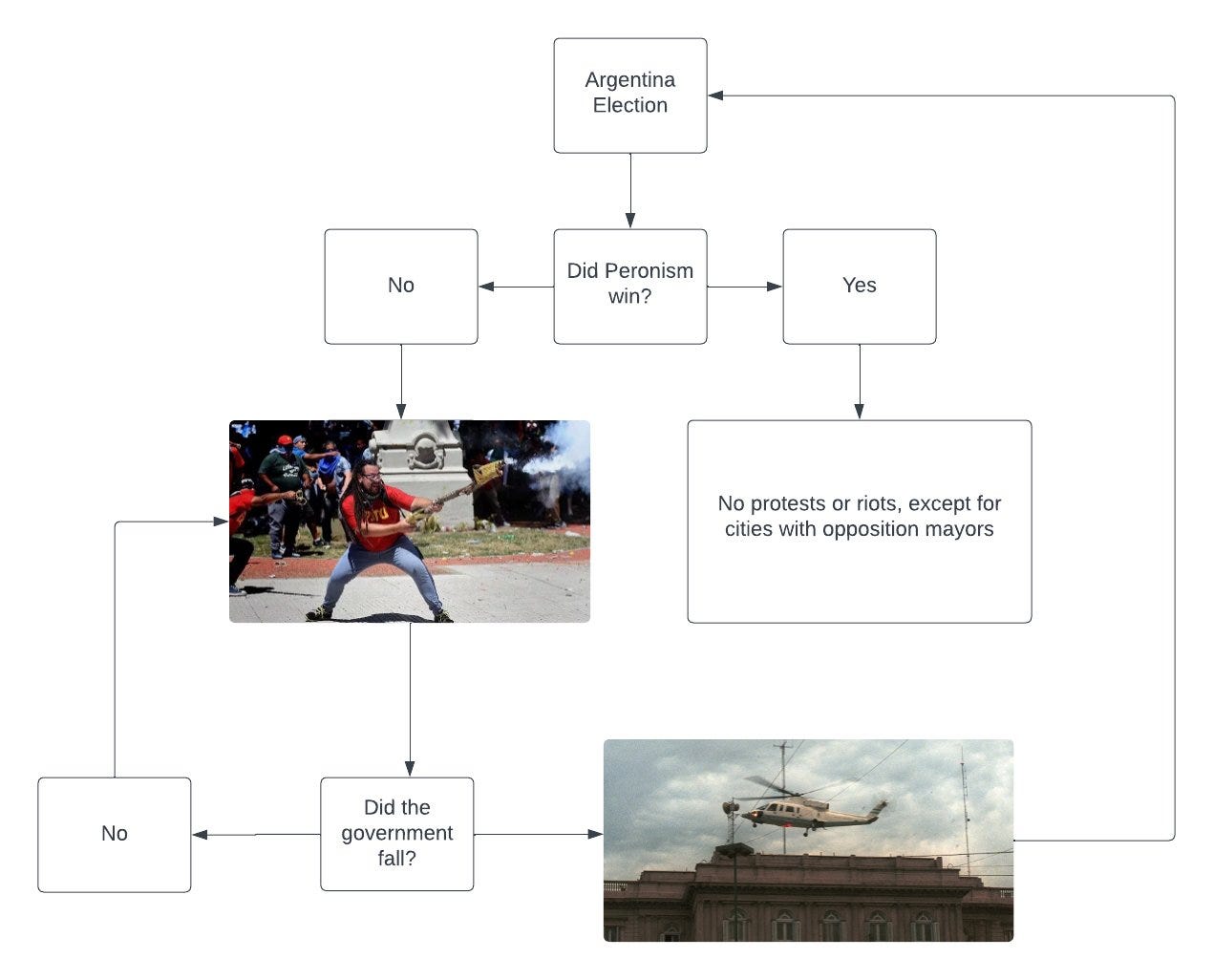

Whenever Argentina has hit rock bottom, the modus operandi for the governing Peronist party has been to drop the bomb in someone else’s lap, wait for it to go off, and come back to save the day.

“See, only the Peronists can clean up this mess and govern Argentina, anything else is a recipe for disaster,” is a line of thinking that reverberates from the party top to its most fanatic supporters at the bottom of the political food chain.

This is one of the reasons I created this flow chart initially after Javier Milei won the runoff against Sergio Massa in November 2023:

We are nearing an interesting point in time where many of the economic and political decisions made by the Milei administration will start to show their effect.

At the same time Argentina has also just hit the rock bottom in Q2 of 2024, with a record 50%+ poverty rate that was left by Alberto Fernández and Sergio Massa — a minor detail many media outlets prefer to leave unmentioned in their headlines, while blaming the malaise on Milei’s policies.

One interesting dynamic, which might also coincide with a different macro economic scenario, is that this time foreign investors are “waiting it out” more compared to the local population: during Macri it was almost in reverse.

If Milei is able to cement his party’s presence in the 2025 Midterms, we can rest assured that La Libertad Avanza has a lot more runway in the years to come.

But never forget that as more voices start to call for “Peronism is done for”, the bigger the surprise will be once the pendulum swings back and that fixed 30% starts to creep closer to 45% again.

Until now, Hasta la vista, baby has been quite literally the case: eventually the ping pong ball has landed in the lap of the Peronists time and time again.

The best way to prevent a comeback of Marxist Peronism (Kirchnerism) or to have a more moderate and more pro-market Peronism in place — like in the 90s during the Menem years — is if Milei’s policies turn out to be very successful.

Besides economic growth and ending rampant inflation, another key to long term success will be to not to give into the corrosion of conformity. If Milei decides to store his radical chainsaw by transforming into the status quo political class of old, that will almost certainly initiate a comeback of the opposition.

After all, if there’s nothing to shout against, people get bored quickly in the country that is never boring. Luckily there are still enough insane regulations and taxes for Milei to keep ramming his chainsaw through for the foreseeable future.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Nostr: increasing my posts here, my npub: npub1sngpxenyrddqvnusf02fls8yl0ja3s373md9lmfkej2l0h6saz6qvglthh

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

Spouse as VP is crazy. Is that still legal?

Great post!