Pravda/12 & La Tablada

How Nicaraguan Sandinistas funded one of Argentina's mainstream newspapers, and the mayhem that followed.

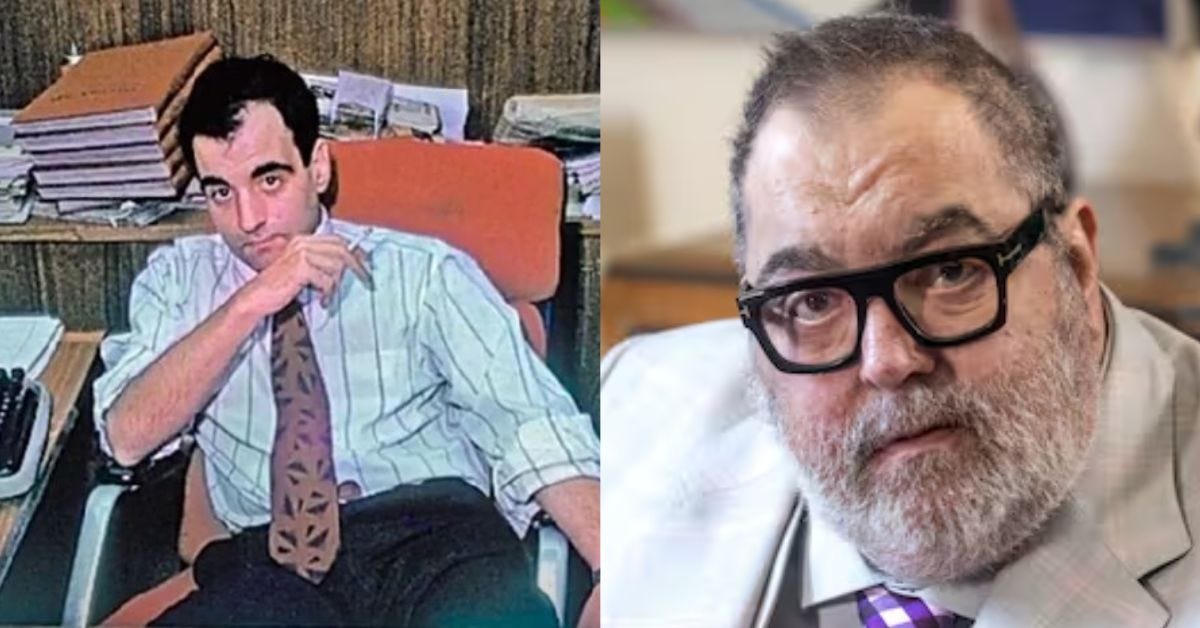

Welcome Avatar! In 1987, journalist Jorge Lanata received Sandinista funding from Nicaragua to launch newspaper Página/12. Through this medium, Lanata, Gorriarán Merlo, and other MTP militants would incite a coup attempt and siege of the La Tablada army barracks in 1989, which ended in a bloodbath.

After reading that intro many will think that after that whole ordeal Página/12 would no longer be in circulation. Nothing is further from the truth. As we’ve seen time and time again, most actions in Argentina do not have consequences, at least not long lasting ones, and this story is no exception to that rule.

Let’s start at the beginning.

The final days of the Junta

After the Falklands War ended in 1982, the Military Junta was standing on its last legs and the big wave of arrests and forced disappearances through the State terror of the 1970s was pretty much over.

These circumstances gave way to more press freedom and less censorship, and slowly but surely more publications critical of the political situation were starting to circulate, with a new generation of journalists.

Democracy would make radio broadcasting the most dynamic and direct medium in which Argentines would seek for information after many years of censorship.

The state-owned Radio Belgrano would be one of the leaders of this era, where progressive journalistic proposals began to emerge.

El Porteño was a newspaper founded in 1982, in the last year of the military dictatorship. Several of the journalists working for Radio Belgrano —including Jorge Lanata— were part of the staff of El Porteño, and it was in the radio studios and the founding meetings of newspaper Página/12 would be held.

Jorge Lanata & Página/12

Up until recently, Jorge Lanata was one of the most influential mainstream journalists since the return of democracy in Argentina. His origins are very different from his later stances against the Kirchnerist governments, as we will see below.

Lanata was part of El Porteño newspaper staff, which acquired a strong dynamic in the first years of Argentina’s regained democracy from 1983 to 1986. Página/12 was launched almost consecutively, on May 25, 1987, with several members of El Porteño on its staff, the same journalistic tone and a similar aesthetic.

For many decades the founding story of Página/12 was not told in all its nuances with the exception of the book “Grandes Hermanos” by Eduardo Anguita, which told the story of how Página/12 was financed in part by Sandinistas from Nicaragua for the first time.

In this book, Anguita recounts the decisive part of the birth of Página/12. One of El Porteño’s main contributors, Hernán Invernizzi, put journalist Jorge Lanata in contact with Fernando Sokolowicz and Francisco Provenzano, who would obtain the necessary funds from the Sandinistas and Enrique Gorriarán Merlo to found Página/12.

After denying it for years, in an interview1 with Noticias magazine in 2009 Lanata acknowledged the contribution of funds from the Sandinista guerrilla for the founding of Página/12:

“At the beginning of the newspaper I was working on a book about political prisoners during the dictatorship. And I began to have a relationship with some guys who had been in the ERP2.

They introduced me to the “nica”, the Nicaraguan Sandinistas of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, related to the Todos por la Patria Movement and its leader Enrique Gorriarán Merlo.

Francisco Provenzano would be one of the few militants with combat experience to enter the RIM3 of La Tablada a few years later. He would be one of those shot alive at the time of surrender […]

Honestly, if you ask me if I saw Sokolowicz with the suitcase with the money, no. Both he and I had a relationship with them, but I never got involved in the money.”

To understand the levels of political insanity that would gain a foothold in one of the three main newspapers in Argentina with Página/12, a deep dive into the sinister figure of Gorriarían Merlo — the man carrying the suitcase with Sandinista funds needed for its launch — is in order.

Enrique Gorriarán Merlo

Back in 1970, Enrique Gorriarán Merlo was one of the leaders of the Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT) which, at its Fifth Congress, decided to start an armed wing: the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP).

In March of that same year Gorriarán Merlo joined the clandestine armed struggle.

It was always speculated that he was a double agent or at the service of American interests because he always came out unscathed from every army confrontation and mass arrest carried out against the ERP movement.

Eventually he would be arrested in Córdoba in 1971, together with a few others, and he was shipped to the Rawson prison, all the way down in Chubut (Southern Argentina).

On August 15, 1972, Gorriarán Merlo starred in a cinematic escape from the maximum security prison along with 109 other guerrilla leaders from various political groups. This event later led to what was known as the Trelew Massacre, where 16 of the recaptured fugitives were executed by the military dictatorship under Lanusse.

Gorriarán Merlo managed to board a plane to Santiago de Chile, where Salvador Allende was governing, a friendly socialist who protected him against extradition. He then traveled to Cuba and returned to Argentina in December 1972.

He was pardoned by the new Peronist government of Héctor Cámpora, who took office on May 25, 1973 — who headed an interim government to clear the path for Perón, who would finally return from his 18-year long exile in Spain and win the elections later that same year.

The following year, on January 19, 1974, Gorriarán Merlo commanded the attack against the military garrison in the city of Azul, Province of Buenos Aires. The attack was a failure and the main reason for president Perón to redouble his efforts with the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (AAA), the unofficial group that would start disappearing and killing leftwing guerrilla members across the country.

With the arrival of the military dictatorship in 1976, Gorriarán Merlo went into exile in France and later established relations with the Sandinista National Liberation Front of Nicaragua. Accompanied by a group of PRT militants, he went to Nicaragua in 1979 to join the revolutionary process.

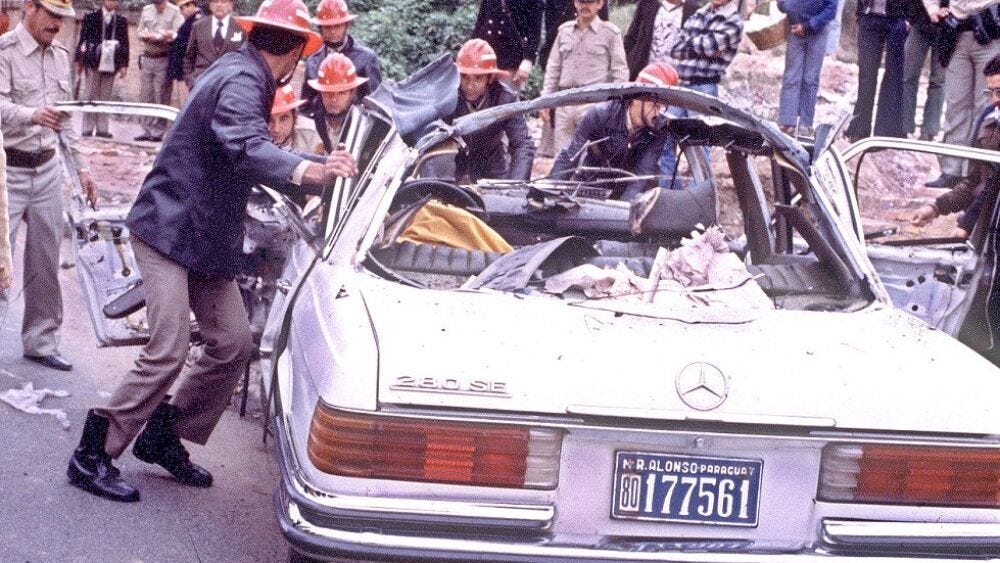

Gorriarán Merlo commanded the cell that assassinated former Nicaraguan president Anastasio Somoza Debayle in Asunción on September 17, 1980, after months of surveillance in the Paraguayan capital.

When democracy returned to Argentina, Gorriarán Merlo was tried during the government of Raúl Alfonsín due to his participation in the ERP bombings and terrorist activities in Argentina in the 1970s.

However, in typical Argentine fashion, he was never sentenced and continued his revolutionary activities, founding the ERP-spinoff party Movimiento Todos por la Patria (MTP) in 1986.

We are now the year prior to the launch of Página/12 and the suitcase with Nicaraguan money mentioned by Jorge Lanata and confirmed by Gorriarán Merlo himself in his 2003 autobiography, Memorias de Gorriarán Merlo:

“Among these projects (of the MTP), the main one was the creation of Página/12, which, contrary to all the opinions that predicted a failure after the argument that there was no space for another newspaper, had become a promising surprise, also for those of us who promoted its appearance from the beginning.

The original idea arose during some interviews about the sixties that Jorge Lanata was recording with Francisco Pancho Provenzano and Hugo Biafra Soriani, two former PRT-ERP militants who had been in prison shortly before democracy in 1983.

In their conversations they began to imagine the possibility of publishing a counter-information newspaper, which would give an alternative view of the news published in traditional media and incorporate other news that they avoided dealing with.” — Page 496

If you thought the preamble was crazy, you haven’t seen anything yet.

The Preamble of La Tablada

A mere two years after the launch of Página/12 in 1989, Gorriarán Merlo would lead a guerrilla uprising in the midst of democracy, attacking the La Tablada army barracks. Together with a group of communist terrorists he tried to take over a military base where conscripts were being trained, leaving a balance of 43 dead and 4 missing.

The articles published by Jorge Lanata in Página/12 in those two years leading up to the takeover of La Tablada were openly pro-guerrilla and encouraged popular uprisings of that type.

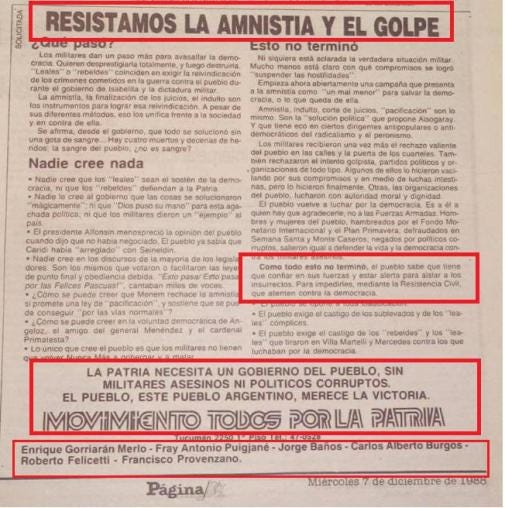

Just little over a month before the attack, on December 7, 1988, Página/12 published an MTP advertisement, signed by Gorriarán Merlo — who had an arrest warrant —, Francisco Provenzano, Jorge Baños, and others, entitled “Let us resist amnesty and the coup.”

In this full page ad, the leaders of the MTP party warned that both the democratic government of president Alfonsín and candidates Carlos Menem and Eduardo Angelóz were seeking an “amnesty” and “pardons” for all high-ranking military officers prosecuted for crimes against humanity in 1985.3

They warned that “since all this is not over, the people know that they have to trust in their forces, and be alert to isolate insurgents. To prevent them, through Civil Resistance, from attacking democracy.”

Gorriarán Merlo himself speaks of the editorial line of Página/12 in his 2003 autobiography and compares it with the militant magazine of the MTP:

“Of the editorial projects that we promoted, only Entre Todos openly revealed our participation. In Página/12 it would have been counterproductive.

But today there is no reason to hide it and it is useful to show that our efforts were centered on essentially political questions, and that La Tablada was not a plan but a circumstance that had been unexpected.”

On December 29, Lanata’s Página/12 insisted on the thesis of an imminent military-Menemist coup, publishing an interview with Jorge Baños, leader of the MTP party and co-signer of the ad earlier that month. In this interview, Baños warned once again that the Armed Forces were about to rise up in arms against the weak government of Alfonsín, and that action had to be taken on the matter.

Autist note: Baños referred to the Carapintadas uprisings, which were a series of four military uprisings that occurred between 1987 and 1990. These rebellions, under leadership of Aldo Rico, were staged primarily to assert displeasure against the civilian government and make certain military demands known — mainly in favor of the presidential pardons for high ranking military leaders that would come later. As you can see, with all these uprisings going on and in the midst of an historic hyperinflation, Argentina was anything but “chill” during its regained democracy. Read more about the Carapintadas movement here.

On January 4 1989, Lanata continued to fuel the revolutionary fire by publishing a column by Pablo Bergel, which was basically a call to arms:

“Democracy is not defenseless: it is made defenseless by those who hesitate and renounce initiative and mobilization. The most shocking thing about the last military uprising was not its own power and deployment but the repeated declaration of impotence of the supposedly loyal leaders and the paralysis of the ruling class in the face of the emergency….

To this end, a day of civil resistance could be called, with the participation of democratic parties, CGT, human rights organizations, neighborhood, social, cultural movements, cooperatives […].

Each resistance group will try to establish in its area of influence a hypothesis of threat to democracy, and reference its actions, large or small, in relation to said hypotheses, creating diagrams of feasible contingencies.”

On January 17, five days before the takeover of the barracks, another well-known MTP leader Carlos Burgos who also participated in the La Tablada attack, published an article in Página/12 titled “An open secret”.

This article evoked a conspiracy theory in which retired colonel Mohamed Alí Seineldín would carry out a coup against Alfonsín’s government on January 24, to commemorate March 24 (the start date of the 1976 coup d’etat):

“The Todos por la Patria Movement announced a new coup attempt led by Colonel Mohamed Alí Seineldín with the support of the Peronist candidate Carlos Saúl Menem and Lorenzo Mariano Miguel […]

As published by Página/12, spokesmen for both leaders rejected the accusations. These same or similar versions are being analyzed by the government, the opposition, human rights organizations and other media. In many of these places, there is talk of a date again: January 24.”

After publishing up to the date on which the coup would take place, this series of articles in line with the MTP story reached its peak on Sunday, January 22, 24 hours before the takeover of the barracks.

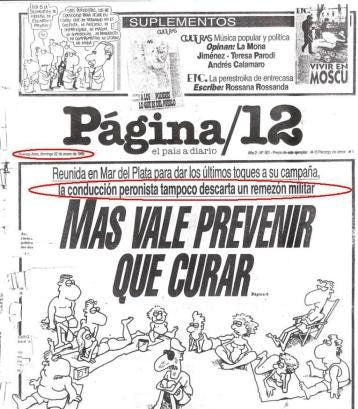

That Sunday, two days before the supposed Menemist-Carapintada coup anticipated by Burgos, Página/12 published an article titled "Better to prevent than to cure." Jorge Lanata was the sole person at Página/12 responsible for the covers.

The subtitle above it said “Meeting in Mar del Plata to give the finishing touches to the campaign, the Peronist leadership does not rule out a military shake-up.”

So in addition to explicitly supporting the imminent arrival of a coup, Jorge Lanata was telling MTP militants — the number one target audience of his newspaper —, to come into action before something worse happened.

On the pages inside, the newspaper also published another article on the possible uprising of the armed forces, without authorship. It was provocatively titled “With one eye on the barracks”:

The article described how “Peronists gathered in Mar del Plata to exchange information on possible outbreaks of military discontent”, and contained a sub-article with the imperative title “Let us be prepared and united.”

Predictive journalism at its best, which should have been signed by its authors Jorge Lanata and Gorriarán Merlo, but that would’ve made it a little too obvious. Without authorship, Lanata could still get the benefit of the doubt if he claimed he didn’t know who wrote it.

January 23 1989: The Attack

When the attack on La Tablada occurred on January 23, 1989, the entire Argentine society was surprised by what was happening. Once again, the guerrillas and the Argentine Army faced each other, resulting in a bloodbath.

But the attack should not have surprised Página/12 readers, as we have seen above.

On Monday, January 23, at 5:30 a.m., a group of 70 MTP terrorists, led by Gorriarán Merlo, went to La Matanza, Buenos Aires province, and entered the La Tablada barracks by force.

Besides catching the military personnel off guard at such early hours in the morning, the guerrillas also chanted “Viva Rico” and dropped pamphlets, as a reference to Aldo Rico, the Carapintados leader, to sow more confusion and to make it seem like the uprising was a military coup against the government.

See some video moments from that day here:

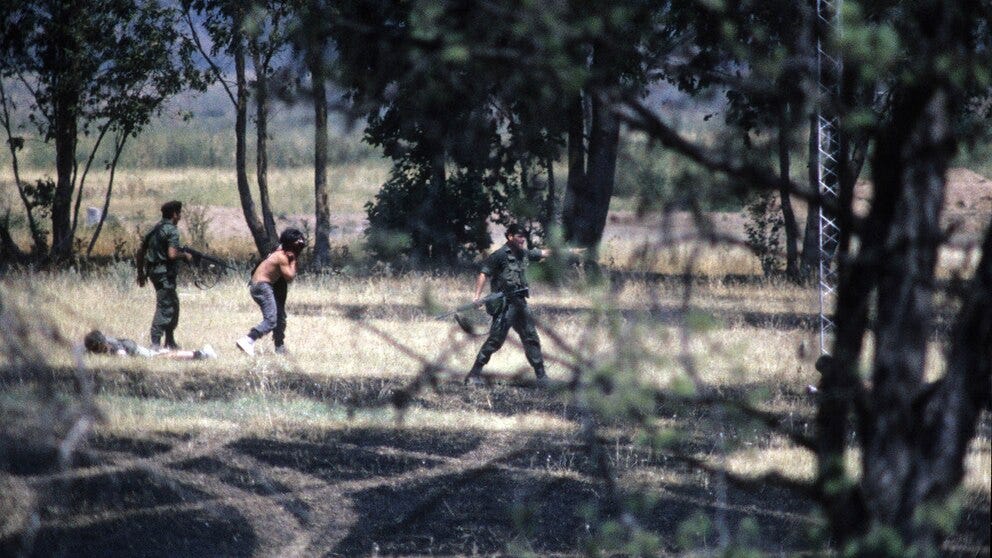

The army, without opening any negotiation process like it did during the Carapintada uprisings of 1987 and 1988, unleashed its artillery of machine guns, cannons, tanks and even white phosphorus projectiles, which were officially prohibited for use.

All the available military tools from the times of the last military dictatorship were used, and in this sense the La Tablada battle was a condensed miniature of what happened during the 1970s between the army and guerrilla groups.

The final death toll was a total of 32 MTP militants, 9 soldiers and 2 policemen. Among the deceased militants were Baños and Burgos, the two MTP leaders who had used Página/12 to denounce that a “Carapintada military coup” was coming on January 24 just a day before, and that “something had to be done” to prevent this.

Besides these casualties, Gorriarán Merlo’s military operation left four MTP militants kidnapped and disappeared, just like this would have happened during the dictatorship: Carlos Samojedny, Iván Ruiz, José Díaz, and Pancho Provenzano — the latter was the one who connected Jorge Lanata with Gorriarán Merlo to get the funding needed to launch Página/12.

These are the first people to disappear during democracy, and their cases reached the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The cases remain open, since their bodies were never found. There are photographic records of two of them, Ruiz and Díaz, of when they were arrested alive.

Shortly after, as during the dictatorship, they vanished from the face of the earth until today.

Giving credit to the suspicion of being on a payroll as a foreign agent, Gorriarán Merlo got away in the nick of time, like all the previous times cited above.

Lanata’s guerrilla friend was well aware of the saying that a “soldier who flees is good for another war,” and Gorriarán Merlo decided not to enter the barracks at the last moment.

In his own words he did this to exercise strategic leadership of the confrontation from the outside, and he claimed that his objective was to attract media attention and trigger a “popular insurrection” that would prevent the military coup which according to Lanata’s Página/12 would occur the following day.

Carlos Reyes, a cameraman for Channel 13 who covered the attack, said he saw Gorriarán Merlo four blocks from the barracks, in a jeep, dressed in military clothing alongside other soldiers:

At noon, when everything had calmed down and you couldn't hear so much shooting, something remained in my memory to this day.

We started walking and asking people what they thought about what had happened. 400 meters away, next to a gas station, there was an Army Jeep with four officers.

We wanted to talk to them but they didn't pay any attention to us. And we were left wondering: what were they doing there looking at if they were officers?

They were four terrorists who were looking at everything dressed as soldiers. We continued walking and 50 meters away a bomb hit us and destroyed a wall. […]

Later, with the image of Gorriarán Merlo all over the media, I noticed that he was one of the guys I saw in the Jeep. I wanted to die. I felt like a real idiot. I had these guys next to me just a meter away. They were just sitting there. To this day I have that image”.

This only fuels the suspicions of Gorriarán Merlo playing multiple roles even more, but the final word about that is still out in the open and chances are we will never know his true role in all these attacks.

The day following the La Tablada attack, Jorge Lanata published a large cover for Página/12, with a vague title that could go down in the annals of anti-journalism for saying absolutely nothing: “Death is a commonplace.”

Furthermore, he asked “questions” on who could’ve possibly been responsible for the attack, and described the attackers as a “comando group”.

It would be hard to defeat those levels of hypocrisy, even though media outlets never fail to deliver.

The End of the Line for Gorriarán Merlo

As was the case with most of the military operations in which Gorriarán Merlo took part, the MTP takeover of the army barracks was a resounding political and military failure. Paradoxically, Gorriarán's followers received harsh sentences for having attempted a coup d'état and an attack on the democratic order.

The MTP leader fled the country and was later arrested on October 28, 1995 on the outskirts of Cuautla in Mexico, and extradited back to Argentina.

After being sentenced to life imprisonment in 1996, Gorriarán Merlo, along with other detained ex-guerrillas, carried out a hunger strike that lasted 162 days, and he was released in 2003 by a presidential pardon from then-president Eduardo Duhalde.

In the last years of his life he was prohibited from entering Nicaragua by the governments of Violeta Chamorro and Arnoldo Alemán; although he enjoyed the support of his dear friend and Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega, the current dictator in Nicaragua since 2007, for services rendered and blowing up Somoza in Paraguay.

Gorriarán Merlo died of a heart attack on September 23, 2006 in Buenos Aires.

As usual, various Marxists fans of death and destruction were quick to honor him post-mortem: Colombian ELN guerrilla group released a statement commemorating the death of the guerrilla, and in Managua, a neighborhood library was named after Merlo in “honor of the combatant who served the Sandinista revolution since 1979”.

Final Thoughts

Not all newspapers are created equally. This is definitely the case in Argentina. This story serves as a mere glimpse into the world of the “Fourth Estate”, which, as we have seen in Peronist Ping Pong, was always tightly aligned with the State.

After the end of the Military Junta this dynamic started to change and new voices like Página/12 started to emerge, financed by the same guerrilla fighters that had terrorized Argentine society before, during and after the dictatorship.

The failed attack on La Tablada was one of the last stands for Gorriarán Merlo and his Marxist buddies, or was it? Their newspaper went on to be one of the big three in Argentina in the 1990s — next to Clarín and La Nación —, and continues in that spot uninterrupted until today.

Jorge Lanata left Página/12 in 1994, 5 years after the La Tablada bloodbath, and started to write for Clarín.

Later during Cristina Kirchner’s presidencies he became one of the main media voices against her presidency, which is remarkable given their shared roots & affinity for guerrilla groups like ERP and Montoneros.

Jorge Lanata is currently hospitalized and in poor health, but not poor enough to try to prohibit the media from speaking about him or speculate about his condition.

To this day, Página/12 continues to write from the same Marxist angle, and it has been a stubborn defender of all the failed Kirchnerist policies that led to 50% of the Argentine population living below the poverty line.

The newspaper has never had to justify the initial funding either in court or in a public statement.

In a future article I will also discuss the Papel Prensa case around Clarín and La Nación, two of the other biggest newspapers in Argentina which also have some bloodstains on them, to say the least.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Nostr: increasing my posts here, my npub: npub1sngpxenyrddqvnusf02fls8yl0ja3s373md9lmfkej2l0h6saz6qvglthh

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

The full interview is only available in print version, only the intro text was published online by Revista Noticias. For a print reference: Alejandra Daiha y Franco Lindner, "El francotirador solitario," NOTICIAS, Buenos Aires, Abril 2009. Pages 86-94, also quoted here.

The ERP (People's Revolutionary Army) was a Marxist terrorist group that started in the 1960s and continued up to the first years of the Military Junta. They blew up public buildings, police stations, military barracks, schools, and the like. This turbulent time in Argentina is covered in Different Types of Condors

This was in reference to a general amnesty that was in the works and that Carlos Menem would sign a year later. Most of the Military Junta had received sentences in 1985 in a groundbreaking case — also see the film 1985 for more background on this trial — and some of the guerrilla members had also received sentences, albeit very few. On October 7, 1989, President Menem approved four decrees pardoning 220 military personnel and 70 civilians, in an attempt to conclude the dark chapter of the military dictatorship years. This undid the 1985 sentences for presidents during the dictatorship years like Videla, Massera and others. Congress declared these decrees null and void in 2003, and judges began to declare Menem’s pardons as unconstitutional and decided to reopen the cases. In 2010, the Supreme Court came out with the final word that the 1985 sentencing was to be upheld.

reminds me of the movie "The Dancer Upstairs". Producers did a pretty good job capturing the LatAm feel which they usually don't. The Marxist intellectuals sure do love their cigarettes...