The Last of the Montoneros

The story behind Mario Firmenich, and why Argentina is seeking justice

Welcome Avatar! The 1970s were one of the most turbulent decades in Argentina, and for many guerrillas and military junta members alike, justice was either served late or never. The latter is the case for one of the last founding Montonero members still alive: Mario Eduardo Firmenich, but a recent Court of Appeals decision might change that.

“In a country that has experienced a civil war, everyone has blood on their hands.”

— Mario Firmenich

Last December, a Court of Appeals ruling marked a historic turning point in the cases of crimes committed by guerrilla groups in the 1970s. Until now, these crimes were considered to have expired because they were “common” crimes, not perpetraded by the Military Junta. The court ordered the reopening of the criminal investigation into the attack on a federal police cafeteria on July 2, 1976, which killed 24 people and injured around 60.

The decision of the judges coincides with the position put forward by Vice President Victoria Villarruel, who demands justice for the victims of these attacks as part of what she calls “complete memory.” The judges ordered Mario Firmenich, the former leader of Montoneros, to be summoned for questioning.

Earlier in July, Firmenich had already made his first public statement in a long while, addressing young leftist militants in Argentina, and condemning Villarruel’s crusade against him and his terrorist buddies.

In that same message, he also invited young people to analyze whether there are reasons to repeat an experience like that of the Montoneros group in Argentina today:

“Are they circumstantial historical factors or permanent factors? These factors were at the origin of Montoneros and therefore are decisive in the historical weight achieved by the organization at its peak and even afterwards.

The question to be answered is whether these factors were unrepeatable or recurring circumstances. If there are factors that are unrepeatable, then there is no way to try to repeat a political event like the one that Montoneros had in its time. If there are factors, on the other hand, that are permanent, it is a matter of taking them into account to see how you, young militants today, can make these factors operational in order to develop a popular political alternative of significance.”

Remorse is a word that does not appear in the Firmenich dictionary. Vice President Villarruel responded to his justifications in a tweet, which ended with:

“I want to tell these terrorists of the past and present that my intention to put them in prison is not only mine, but that of millions of Argentines fed up with the business they made in the name of human rights, fed up with the atrocious crimes for which they did not pay and disgusted by the moral superiority with which they speak to us when they are murderers.”

Her intention is now shared by the Court of Appeals. The judges overturned the dismissal ordered by a court of first instance. In their ruling, they argued that the bomb attack constituted “a serious violation of human rights” because the courts did not investigate the events during the military dictatorship or clarify what happened to the families of the deceased.

Considering it an imprescriptible crime, the Court of Appeals annulled the dismissal of Firmenich, and the other leaders of the group. But who is Mario Firmenich, and how come he is not locked up for good?

A Bloodstained Curriculum

Firmenich was part of the founding group of the Montoneros guerrilla organization, along with Fernando Abal Medina and others.

The ideology of the organization interpreted Peronism as the only revolutionary political form, adapted to Argentina’s situation and fused with elements of Catholic nationalism and the Cuban socialist revolution. A ideological hodgepodge that would result in a powerful Marxist molotov cocktail, and many casualties.

One of the first “milestones” of Montoneros’ path of death and destruction was the kidnapping and assassination of former de facto president General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu on May 29, 1970, after subjecting him to a “popular trial” in the basement of a ranch located in the province of Buenos Aires.

Aramburu was snatched from his apartment in Buenos Aires city by two members of Montoneros posing as young army officers. The crew of 12 guerrilleros dubbed the kidnapping Operación Pindapoy, after a company that produced citrus in the 1960s.

Firmenich reconstructed Aramburu's last moments before his death:

“He tried to move us. He spoke of the blood that we, young boys, were going to shed. After half an hour, we untied him, sat him on the bed and tied his hands behind his back. He asked us to tie his shoelaces. We did. He asked if he could shave. We told him there were no razors. We took him down the inner corridor of the house towards the basement. He asked for a confessor. We told him that we could not bring a confessor because the roads were patrolled.

"-If they can't bring a confessor," Aramburu said, "how are they going to get my body out? What will happen to my family?” he asked.

He was told that there was nothing against his family, and that their belongings would be returned to them. The basement was as old as the house, seventy years old. We had used it for the first time in February 1969, to bury the rifles expropriated from the Córdoba Shooting Range. The stairs wobbled. I had to go ahead to help him down.

"-Ah, they are going to kill me in the basement," he said.

We went down. We put a handkerchief over his mouth and placed him against the wall. The basement was very small and the execution was to be done with a pistol. Fernando took it upon himself to execute him. For him, the boss should always assume the greatest responsibility. He sent me up to hit a vise with a key, to hide the sound of the shots.

“-General,” said Fernando, “we are going to proceed.”

“-Proceed,” said Aramburu.

Fernando fired a 9mm pistol at his chest. Then there were two coup de grace shots, with the same weapon and one with a .45. Fernando covered him with a blanket. No one dared to uncover him while we were digging the hole in which we were going to bury him.”

In that same 1974 interview in Causa Peronista, Firmenich explained:

“The execution of Aramburu was an old dream of ours. We conceived the operation at the beginning of 1969. There was a principle of popular justice involved - reparation for the murders of June 1956 - but we also wanted to recover Evita's body, which Aramburu had made disappear.

But we had to let time pass, because we had not yet formed the operative group. At the end of 1969 we thought it was possible to undertake the operation.

Because of the political importance of the event, because of the meaning we attributed to our own appearance, we went into the operation with the criterion of all or nothing. The initial group of Montoneros played it to the head or tail in that event.”

In September of 1970, Abal Medina and other founding Montonero members were killed, and when one of the last founders, José Sabino Navarro, was killed in July 1971, Mario Firmenich became the head of the organization.

Declared Peronists, the guerrillas then had the tacit approval of Perón, who had been exiled in Spain since 1955. However, when Perón returned to the country after 17 years, he tried unsuccessfully to deactivate the armed organizations like Montoneros and ERP, failing to do so. By then, the country plunged into an unstoppable spiral of violence and death.

Autist note - Perón’s presidencies had a lasting impact and led to a subsequent anti-Peronism. This article dives into that dynamic that is still very much at play up to this very day:

On the day of Perón’s return to Argentina, right wing Peronists led by José López Rega and Colonel Jorge Osinde who were in charge of organizing the multitudinous welcoming event, exchanged fire with the Peronist Youth and the Montoneros, as both factions fought to occupy the first place in front of the stage.

This shootout behind the stage is referred to as the Masacre de Ezeiza, which left at least 13 dead at the Ezeiza airport, and about one hundred more were wounded.

Firmenich was also at the airport to welcome Perón, and recalls:

“We left Ezeiza without knowing what had happened, because everything happened behind the stage. What I remember from that event is the most incredible disappointment of the biggest event I have ever seen in Argentina and outside of Argentina, without a speaker, without anything. A multitude of people. Millions, so many people, as far as the eye can see. And the people left with a sadness and a dismay that I will never forget.”

But the Ezeiza massacre would only be the starting sign of more sadness to come, inflicted by Firmenich and his Montoneros during Perón’s democratic government, with right wing Peronist factions in the form of the Triple A doing their fair share of kidnapping, bombing and murdering as well.

Firmenich has been implicated in numerous legal cases for crimes committed by the Montoneros during those years, including the murder of trade unionist José Ignacio Rucci in 1973, assassinated two days after Perón won the presidential elections.

Rucci was one of Perón’s close confidants, but according to the Montoneros he was part of the “wrong” type of Peronism.

At Rucci’s wake, Perón said that they had killed his son, that those bullets had been for him, and that they had “cut off his legs.” Firmenich would later admit that killing Rucci had been a political mistake. Rucci’s daughter, Claudia Rucci, was appointed by the Milei government to shed more light on the civilian casualties during those years, and currently heads the Human Rights Observatory of the Senate.

After Rucci’s assassination by Montoneros, Perón submitted a bill for anti-subversive legislation to Congress, where left-wing Peronist deputies refused to vote for it. The legislators resigned and the Montoneros leadership distanced itself from the Perón government. The wave of violence, murders, attacks and takeovers of military units continued.

Autist note - This article goes into more detail of the preamble to the 1976 dictatorship, that starts with Perón’s return to Argentina and his death in 1974, the military coup itself and the aftermath:

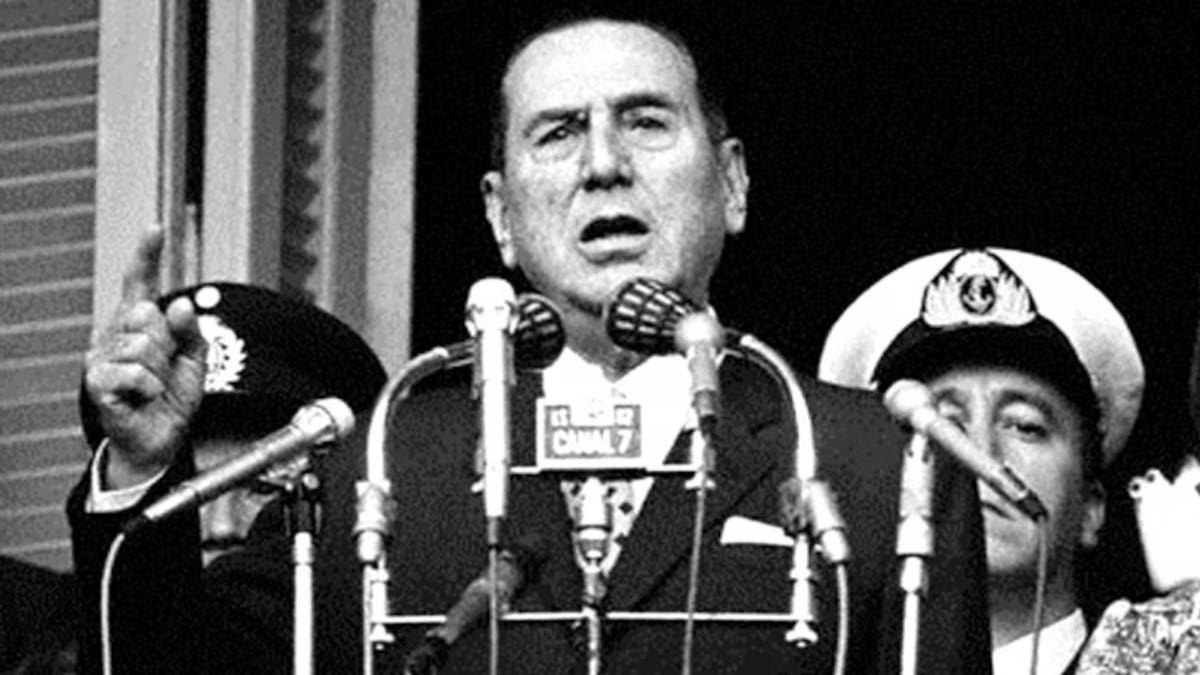

The final break between Peronism and the Montoneros was during the Labor Day ceremony in Plaza de Mayo. On May 1, 1974, behind bulletproof glass — an unthinkable setting in Peronist liturgy on the balcony of the Casa Rosada — Perón referred to the Montoneros as “stupid” and “beardless”, and half the plaza was left empty when they left.

With Perón’s widow taking over the presidency after his death in 1974 — Isabel was the Vice President, — the Montoneros kicked things into overdrive.

Firmenich claimed responsibility for the murder of the head of the Federal Police, Commissioner Alberto Villar, and his wife, placing a bomb on the yacht they were sailing on the Tigre Delta. Some other high profile Montonero assassinations like the one of businessman Francisco Soldati and undersecretary of planning Miguel Padilla deserve an article of their own, and were also claimed by Montoneros.

The Cafeteria Bombing & Case

The bombing of the Federal Police cafeteria in 1976, which is now once again in the spotlights in the Court of Appeals, was one of the ‘highlights’ of Firmenich’s terrorist career.

The decision of the judges today is limited to the events that occurred at 1:20 p.m. on July 2, 1976, when a bomb exploded in the dining room of the Federal Security Superintendence, located at 1431 Moreno Street in Buenos Aires. The ruling states:

“The leadership of the non-state armed organization “Montoneros” had meticulously selected that site to communicate to the security forces, and through them to the entire Argentine people, their presence, their offensiveness and their ability to eliminate any obstacle that stands in their way.”

Moments after the explosion, a statement from the organization claimed responsibility for the event, boasting about “blowing up 40 diners” at the station. The bomb left a total of 24 dead and 60 heavily wounded and mutilated.

Shortly after this bombing and the intensification of State terror led by the Military Junta, Firmenich escaped the country to save his life. He subsequently lived in Italy, Mexico and Cuba.

Previous Sentencing and Release

In 1984, Firmenich was arrested in Brazil and extradited following an extradition request made by the democratic government of Raúl Alfonsín. He was tried and sentenced to 30 years in prison for homicide and kidnapping, along with his fellow leaders of the Montoneros organization Fernando Vaca Narvaja and Roberto Perdía.

President Carlos Menem granted most of the parties involved in State terror and guerrilla terrorism pardons in 1990, in an attempt to “turn the page” and forget about the 70s.

Upon leaving prison, Firmenich abandoned politics to study Economics at the University of Buenos Aires. He eventually settled in Spain and became a professor in the Department of Economics and Business at the Rovira i Virgili University, in Reus, province of Tarragona.

His CV does seem to be missing the relevant mentions of practical experience in blowing up cafeterias and assassinating politicians and business men.

His few political appearances since then have had to do with his involvement with the Ortega regime in Nicaragua, which he advises and which usually invites him to major state ceremonies, as well as calling him up to oversee elections that have been ignored by the vast majority of the world's democracies.

Autist note: in 1989 while Firmenich was doing time, another acquaintance of his from the 1970s guerrilla days was planning a Marxist coup in Argentina. This is the story about La Tablada and Daniel Ortega’s involvement in that attempt:

Conclusion

Will Mario Firmenich finally face justice? It is hard to tell at this point after so many years. He was able to get a degree, move to Spain, and live comfortably as an economics college professor at the university in Reus, Catalonia. With his bloodstained CV, Firmenich is not someone who should be teaching economics classes in Spain, to say the least.

He has since moved to Nicaragua, to aid his dictator friend of old Daniel Ortega, who seem to call on Argentina’s worst guerrillas like Gorriarán Merlo and Mario Firmenich whenever he needs them to blow someone up or start an uprising in another country.

The terrorist turned economics professor Firmenich does appear in the 2024 Disney+ documentary Argentina ‘78, about the World Cup organized in Argentina during the Military Junta. The film was released right before the Court of Appeal’s decision in December to investigate the cafeteria bombing as a crime against humanity.

This will probably be end up being the only testimony given by Firmenich.

In that interview, Firmenich justifies his and Montoneros’ actions, comfortably leaving out the fact that Montoneros started bombing, kidnapping and murdering ‘opponents’ years before the 1976-1983 dictatorship, during democracy as well — even during Perón’s short-lived last democratic presidency.

So far Firmenich hasn’t made attempts to travel to Argentina to testify on his 1976 bombing. Ortega will not extradite him, and it is unlikely that he will set foot in Argentina again where he could face consequences for his acts (again).

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

Hijo de mil puta, él y todos los otros cabecillas montos que ni siquiera tuvieron la decencia de matarse y vendieron a todos sus compañeros para comprar su libertad.

Hijos de puta también los que en democracia les dieron cargos públicos y flashan superioridad moral ante el resto de la sociedad.

Fuck this guy, hope he swings