Finding Fair Prices in Gresham's Paradise

Currency competition, exchange rates, export tariffs and Davos

Welcome Avatar! The Milei government gave the starting sign for full currency competition, with the so-called “endogenous dollarization”. Will this be the beginning of lower prices? Let’s dig in.

The Start of “Endogenous Dollarization”

In a key step towards a dollarized economy, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) approved a regulation that will allow businesses to accept payments in dollars with debit cards.

This step is in line with Milei’s strategy of currency competition, which some media outlets have started to call endogenous dollarization:

“The current approach — dubbed “endogenous dollarisation” — entails curtailing the supply of pesos, forcing Argentines to use their dollars to pay for everyday expenses. Over time, that’s supposed to increase the amount of dollars in circulation and reduce reliance on the peso, which has lost 62 percent of its value since Milei took office.”

According to some estimates, Argentines have about 8+ Central Banks tucked away under their mattresses, to the tune of $261 billion dollars, and over $400 billion dollars in undeclared funds offshore.

A first step of getting those dollars back into the economy and banking system was the initial tax amnesty last year, which brought in around $20 billion dollars of those funds.

Starting February 28, any consumer will be able to choose between paying in pesos or dollars with the same card, which marks an advance in currency competitiveness promoted by the Government.

The BCRA highlighted that this measure seeks to promote “currency competition” in daily transactions:

In order for businesses that want to accept payments in dollars with debit cards to be able to do so, the BCRA ordered that acquirers and sub-acquirers (companies that act as intermediaries between the merchant and the clients to process payments) develop and make available the necessary tools for this to occur before February 28.

Additionally, the Board decided to incorporate debit card payments in pesos and dollars into the interoperable QR system, expanding the options that already included interoperability for payments with transfers, credit cards, and prepaid cards. This measure expands the possibilities and improves the experience of customers and businesses that will be able to make and receive payments with any instrument they have enrolled in their wallet, simply by scanning any QR code.

It has to be said that the BCRA regulation is focused on dollars because so many locals have dollar accounts, but it does not mean that prices cannot be displayed in other currencies. For example if a vendor wants to display prices in Bitcoin, he can. It’s just that the BCRA can enable payment railways like debit cards and PoS for local USD accounts, which it can’t for other currencies.

For Argentines this means that they can make payments in dollars without conversion: debit cards linked to dollar savings accounts can be used directly for transactions in that currency. There will be no conversion of pesos to dollars, avoiding complications related to different exchange rates.

The system will be mandatory for banks, but for businesses it is voluntary and they will have the option to adopt this modality according to their interest. Greater adoption is expected in sectors such as household appliances, automobiles and other higher-value consumer items. In order for companies to be able to receive payments, they will have to have a USD account. Various banks have already announced digital tools to facilitate this process, making it easy for businesses to get an additional USD account if they don’t have one currently.

According to Gresham’s Law, if there are two forms of currency in circulation, which are accepted by law as having similar face value, the more valuable currency will gradually disappear from circulation, because it will be used as a store of value.

From a historical perspective, a healthy dose of skepticism is in order when politicians assume that Argentine consumers start paying for everyday items in dollars. The dollar has always been the refuge for savings in Argentina, and the local currency is something Argentines try to get rid of as quickly as possible.

This is so engrained in the local psyche, that it’s doubtful this will change on such short notice.

Is the Peso Overvalued?

Does the appreciation trajectory of the peso spell trouble for Milei's administration? As usual, everyone participating in the Argentine economy has an opinion on prices, and digital brokemads and peso earners join forces whenever it comes to complaining about high prices.

But what are fair prices in Argentina? A major obstacle to evaluating this type of criticism is that no one really knows what the “correct” level of the exchange rate is.

Historically, Argentina is now close to overpriced for most items (general food basket, most other products), but very cheap for some others (meat).

Several economists emphasize that Argentina is expensive in dollars compared to the cost of living during Massa's unoficial government — Alberto Fernández basically left the scene once minister Massa became a presidential candidate — at the end of 2023 or during the end of Cristina Kirchner's government.

But it’s important to see things in perspective. The 2019 elections brought in the second biggest local stock decline in history, when the world learned about another Kirchnerist win with Alberto Fernández at the helm:

That moment initiated an inflationary spiral, with an overheated printing press and a market flooded with peso helicopter money. In dollars, you were king of the hill and could have $5-$10 USD steaks at nice restaurants while peso earners saw their salaries go up in smoke.

After December 10, 2023, this dynamic inverted as soon as Milei and Caputo halted the peso printer and started a deflationary policy. Initially they devalued the official rate (which had a huge gap with the blue rate and was fictitiously high), and after that inflation spike, month-over-month inflation has been trending downwards:

Meanwhile, with the 2% and now 1% crawling peg, the official ARS rate has devalued steadily but relatively little, while the black market blue rate has even crossed paths with the official rate, converging and diving below par for one day. The general dynamic is a 10-20% gap between the official rate and the blue rate:

It is not obvious what the “fair exchange rate” should be for the peso, precisely because of the fx restrictions which mean that the government determines the official rate, and the market works with a combination of closer-to-market exchange rates (CCL, MEP) and the black market rate (Blue).

An analysis on currency appreciation after taking the necessary steps to slow down of inflation or even get to deflationary dynamics, reveals that the local currency appreciates with an average of 5%.

The rate and pace of inflation received by the Milei administration were many times greater than what could be considered a normal scenario, which historically tends to lead to greater local currency appreciation in Argentina once this dynamic is successfully reversed:

In this analysis, it is important to bear in mind that the initial conditions faced by Milei's government were much worse than those faced in other countries. To give an example, our database of successful episodes includes the Volcker disinflation in the United States in the early 1980s, which had to face a much lower initial inflation than that left by Massa.

Our database allows us to get closer to the Argentine experience because we can divide the sample in two and only look at the disinflations that started with high inflation. There we can see that the average appreciation of the real exchange rate is a little higher, almost 13%. And if one continues with this logic and only looks at the disinflations that start with inflation of more than 100%, we see that the real appreciation is more than 22%.

In the graph above1 one can clearly see that the currency appreciation is much greater for countries that experienced initial inflation of over 100% once inflation decelerates, and that this appreciation remains at a higher point throughout the 8 years after the start of that dynamic.

Does this mean that the peso is overvalued? As mentioned before this is hard to really know with certainty until the peso free floats as a currency once more.

But if we take the guideline of historic episodes in Argentina with similar starting points, the current peso valuation does seem to indicate that at least Argentina is trending in the right direction, and that this peso appreciation was very much to be expected.

Export Tariffs: ¡AFUERA! or not?

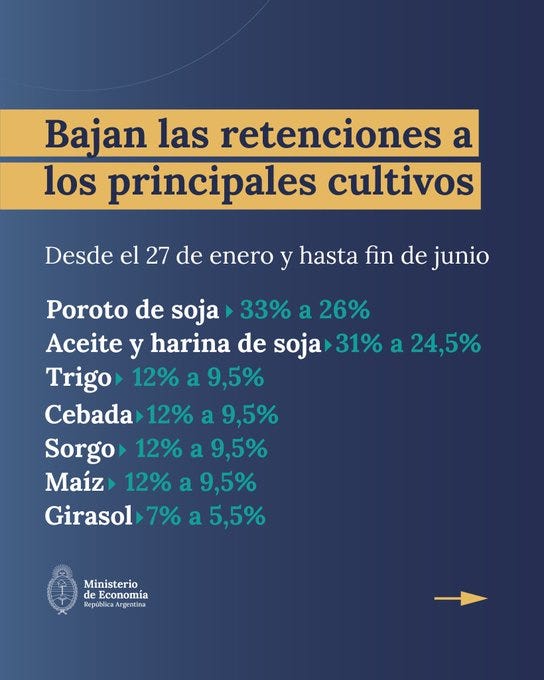

Yesterday, the government announced the elimination of export tariffs for regional economy products like sugar, cotton, leather, rice, and many others.

The most important sector in the madness of Kirchnerism’s export tariffs however, are grains and soybeans. The tariffs on these exports contribute to over 10% of foreign reserves at the BCRA each year, and are a painful but necessary cut for Milei to make. Not lowering these would guarantee a loss of confidence from the agricultural sector, which is crucial.

Finance Minister Luis Caputo announced that the tariffs for those essential exports would be lowered until the end of June:

This is obviously meant to stimulate producers to liquidate and export their crops asap before June, in a hope to boost BCRA reserves before another IMF maturity.

Many producers complained on X about the temporary nature of these lowered tariffs, but my expectation is that Milei keeps the ace for increasing the tariffs again in his sleeve, just in case of an unexpected economic downturn. In practice if the economy follows the path most expect it to, these lowered tariffs will also be confirmed as permanent at the end of June.

Dumping on Davos

After Milei’s star appearance at Davos last year, in this year’s speech Milei focused less on economic principles, with an emphasis on what Milei supporters call the batalla cultural, or cultural battle:

“Today I come here to tell you that our battle is not won, that although hope has been reborn, it is our moral duty and our historical responsibility to dismantle the ideological edifice of sickly Wokeism.

Until we have managed to rebuild our historic cathedral, until we have managed to get the majority of Western countries to embrace the ideas of freedom again, until our ideas are not the common currency of the halls of events like this, we cannot give up because, I must say, forums like this have been protagonists and promoters of the sinister agenda of Wokeism that is doing so much harm to the West.

If we want to change, if we truly want to defend the rights of citizens, we must first begin by telling them the truth.”

The rest of the speech is a continuation of that theme, with many valid points touching on the woke propaganda that has been pushed so excessively in the past decade. Of course, it did not fail to offend a vast amount of people, and Milei once again was the topic of discussion for better and for worse.

During that same Davos visit, the Argentine president mentioned that he is seeking to negotiate a free trade agreement with the United States, and wants changes in Mercosur so that the bloc is not an impediment. In the extreme case, Milei said that he could consider leaving the Mercosur trading bloc if necessary.

Meanwhile minister Luis Caputo did not go to Davos and returned to Buenos Aires to start negotiations for a new disbursement from the IMF.

Final Thoughts

Nothing is ever easy in Argentina, and much less after so many decades of protectionism, tariffs and price distortions.

One thing is unlikely to change: the love for the might greenback as a savings vehicle. Even though Argentina has a higher than average crypto user base, the bulk of that usage is once again concentrated around USDT, a dollar stablecoin. Younger people do save in Bitcoin, but many will still prefer the relative stability and lack of volatility provided by the dollar.

In light of stability towards the 2025 midterm elections, it wouldn’t be that farfetched to maintain the stable crawling peg, while deregulating most other aspects such as the need for currency conversion in different sectors of the economy.

This would be a middle road that is less discussed —the camps are divided between full state control and currency restrictions/cepo and a completely free floating currency without any restrictions whatsoever—, inline with other success stories of stable government controlled currencies that fueled the growth in Singapore and Hong Kong, for example.

But the memory of the 2001 crisis in Argentina, which many blame on the peso being pegged 1:1 to the dollar instead of the deficits that caused that peg to fail, has left a bad aftertaste for many Argentines.

Milei’s currency competition is definitely an interesting experiment and it is an additional step towards currency freedom and less need for conversion. However, the real exchange rate for the peso will only be known once the bandaid of the crawling peg comes off together with the cepo currency restrictions.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

The chart shows the dynamics of the real exchange rate in "successful" international disinflation episodes studied in Di Tella and Ottonello (2024). The horizontal axis represents the years since the beginning of the disinflation, represented by t = 0. The real exchange rate is defined as the ratio between the US consumer price index, converted to local currency using the official nominal exchange rate, and the consumer price index of the local economy, normalized to 100 at t = -2. — Source

Thanks for the Milei update. How would you compare Argentina to Uruguay?

I don't think Gresham's Law applies here. This law only holds if there are price controls in effect -- if the exchange ratios of different monies are fixed and no longer reflect market forces. If Argentina is accepting both currencies but not fixing them relative to each other, there is no reason why the more stable currency should disappear. Right?