Villas & Immigration Reforms

An upcoming Executive Order will make deportation easier in Argentina

Welcome Avatar! In May this year, the Milei government made a complete overhaul of legal immigration policies and the rules around obtaining citizenship. In a decree that will be published in the upcoming days, more migration reforms are coming. Let’s dig in.

The system of private property is the most important guaranty of freedom, not only for those who own property, but scarcely less for those who do not.

— Friedrich August von Hayek

Since the start of Milei’s administration and under the tutelage of Security Minister Patricia Bullrich, there has been a renewed focus on national security, border control, and hammering down on crime.

The Penal Code reform fits in the narrative, and so do the F-16, tank and submarine acquisitions made by the Ministry of Defense during the Milei government so far.

ICE Argentina

Another element that is under review is immigration, and specifically immigration that leans heavily on public social plans, education and/or crime. The latter is the main driver in the initiative to create this “ICE” police force for Argentina.

The government is preparing a decree to reform the National Directorate of Migration, modeled after the United States. The Executive Branch is finalizing the technical details to formalize the creation of a new immigration agency that will include a police force with detention powers at Argentina’s border crossings.

The Casa Rosada denied that this would be a new federal force, but they assure that the aim is to transform the Migrations agency—which currently has an administrative profile—into a structure with its own operational capacity, so that it can carry out the expulsion of immigrants with alerts, records, and irregularities, similar to what ICE does in the United States. This department would coexist with the Airport Security Police (PSA) without overlapping functions.

In July of this year, the Milei government already based its reform of the four federal forces on the U.S. model: It modified the organizational structures, hierarchies, functions, and missions of the National Gendarmerie, the Argentine Naval Prefecture, the Airport Security Police (PSA), and the Federal Penitentiary Service (SPF).

The Casa Rosada has also moved forward with immigration reform through a decree in May which we covered in detail here and here. This executive order established new rules regarding access to public health and education, residency criteria, and grounds for rejection and expulsion.

It also tightened entry requirements, limited the validity of temporary residency permits, incorporated a system of mandatory sworn statements, and authorized border rejections with re-entry bans of no less than five years.

Immigrant Groups in Argentina

At the beginning of the 20th century, almost a third of the Argentina’s population was foreign-born. The gradual disappearance of these early immigrants led to a gradual reduction in the percentage of the population born abroad, but the country still has seen a decent number of immigrants, mainly from neighboring countries, arrive since the early 2000s.

This graph shows the cumulative numbers and nationality for different immigrant groups in Argentina over time:

In the latest 2022 census, the population born in Paraguay and Bolivia had the largest immigrant representation in the country. Of every 100 immigrants, just over 44 were born in one of these two neighboring countries. In 2022, Venezuela’s inclusion on the list was notable.

The Bolivian community has thrived in growing fruits and vegetables, and runs most of the verdulerías in the city of Buenos Aires. They tend to rent fields owned by Argentines to plant their crops. In the case of the Paraguayans, they are most present in construction.

For both of these groups, as for Venezuelans and any citizen from most of South America for that matter, it is very easy to settle in Argentina under the Mercosur residency treaty, which guarantees freedom of residency in most of South America except for French Guyana (which is Europe).

Other non-Mercosur nationals will need a motive to stay in Argentina officially — can be as an employee or through a rentista or pensioner visa, — whereas Mercosur citizens do not. As long as they have a valid ID, birth certificate and a clean criminal record, they can move in and out of any Mercosur country legally.

Villas Miseria

Despite the fact that the majority of these immigrant groups build up a good life in Argentina — at least better than what they would’ve had back home —, the main pain point is housing.

Looking at the distribution of Argentina’s foreign population, more than 73% of foreign-born individuals live in the Province of Buenos Aires and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. And housing is not exactly cheap in these areas, especially if you have to work your way up the social ladder in construction or labor-intensive small scale agriculture.

This has led to squatting of abandoned public — and sometimes private — property, resulting in what are known as Villas Miseria, or shantytowns (Favelas in Brazil). The properties in these villas do not have any deeds or title ownership besides the original owner, but get sold for 10-15k USD from squatters to new arrivals; a circular economy for squatted property of sorts, outside of the system.

The official national map with Villas Miseria, euphemistically known as Barrios Populares, shows 6467 across Argentina, with the majority concentrated in and around the city of Buenos Aires:

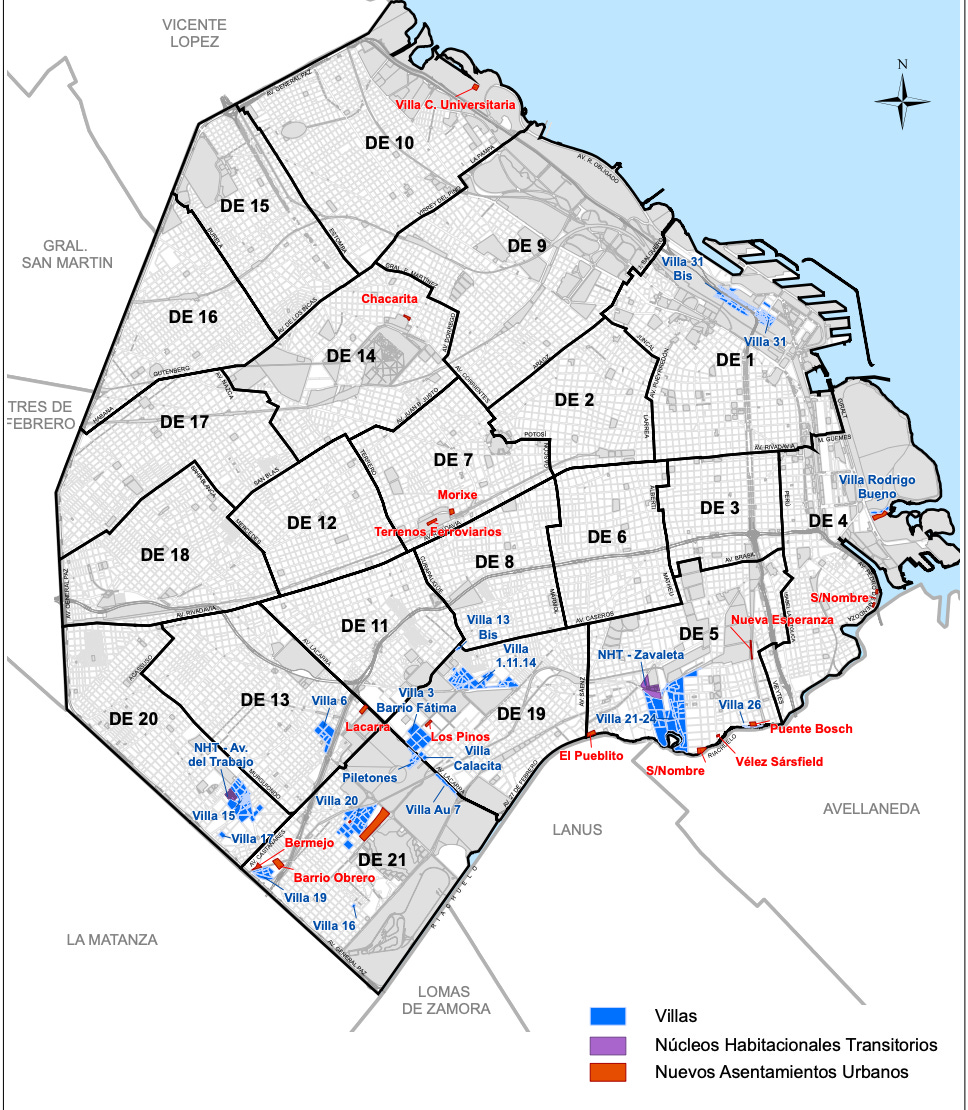

In the city of Buenos Aires alone there are 36 Villas Miseria, all assigned with a number, with a total of 300 to 400,000 inhabitants:

Villa 31 behind the Retiro train station and Retiro bus terminal is probably the most well-known and most frequented whenever Argentines and foreign tourists take a long distance bus to other destinations in the country.

Since none of the properties in these Villas officially exist, there is no way to get a power connection but to steal it from the grid. Similar for other services. You can start to see that besides the squatting itself, this creates more and more problems down the road.

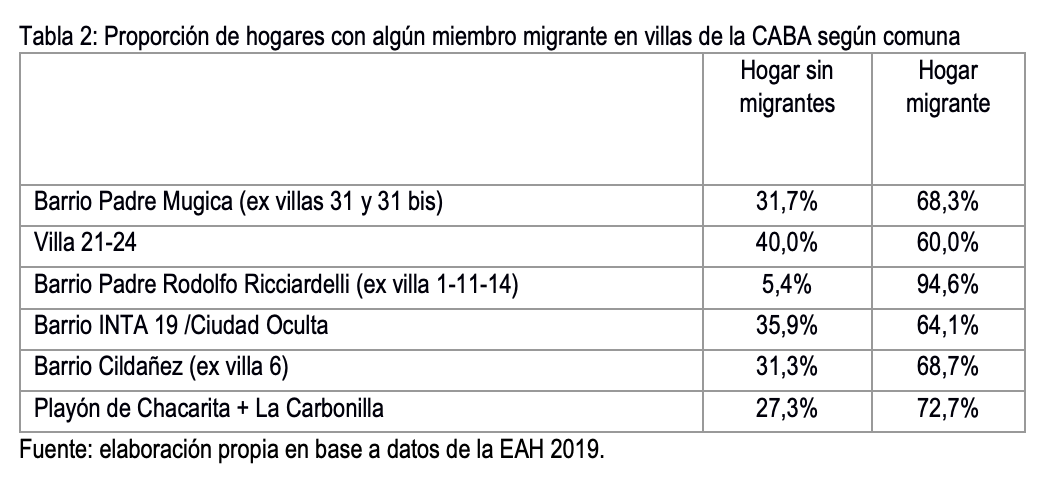

The proportion of households with at least one migrant member in the informal settlements of the city of Buenos Aires reaches 69.2%, compared to only 7.4% in the rest of the city. In some settlements, such as Barrio Padre Rodolfo Ricciardelli (formerly 1-11-14) – District 7 – this percentage reaches 94.6%, meaning that almost all households include at least one migrant member:

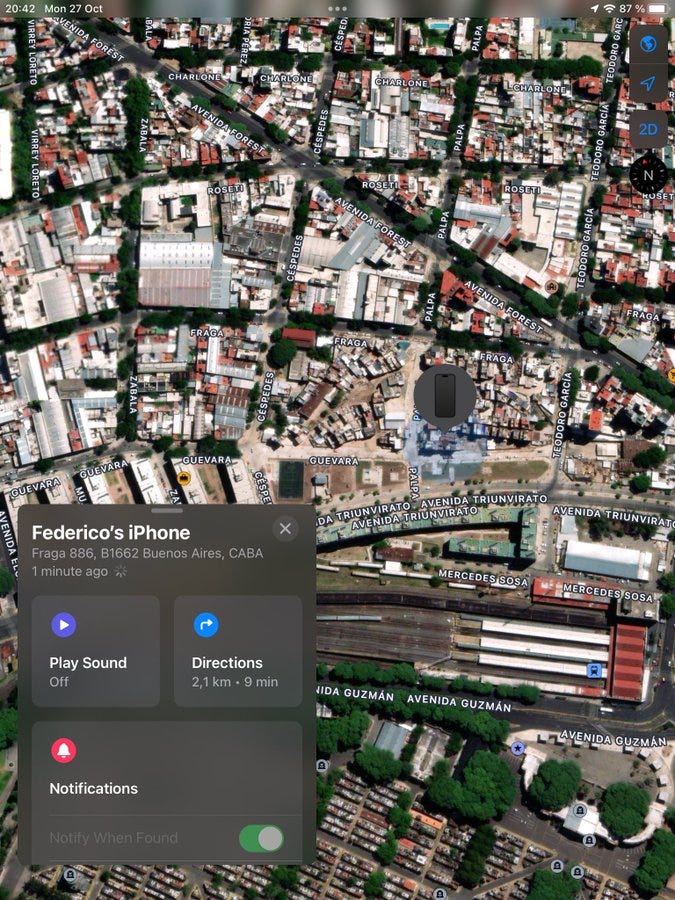

Needless to say that besides the crime itself of occupying public terrains, there is also a concentration of narco and criminal activity in and around these Villas, with many a cell phone tracker ending up in one of these villas shortly after being snagged from its rightful owner. Police will not enter, despite the pings leading to the exact location.

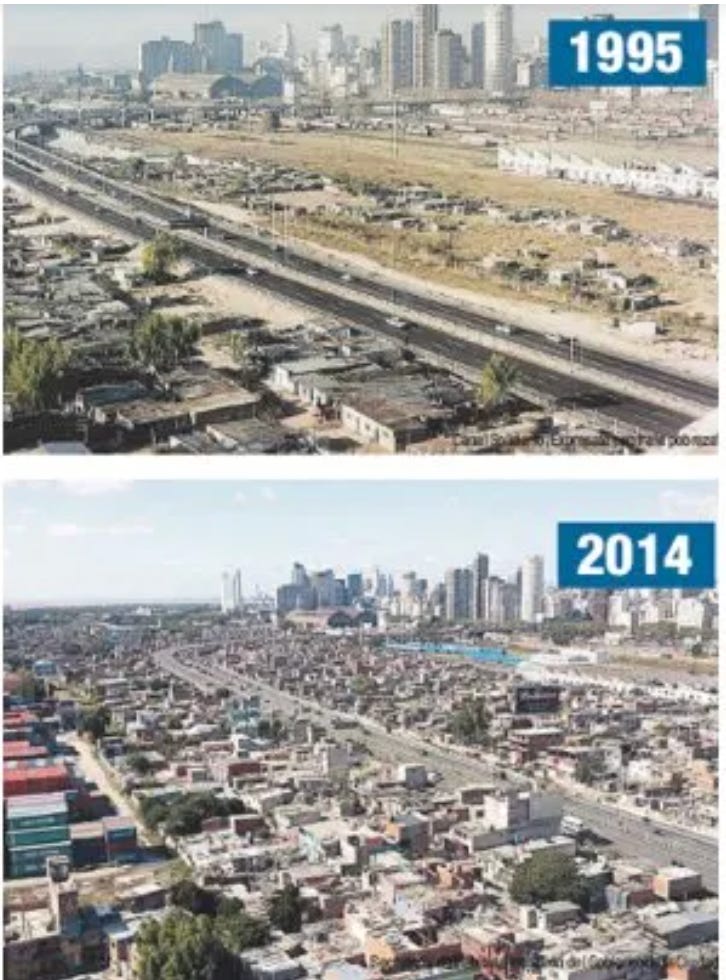

There have been some attempts to “urbanize” the villas in Buenos Aires, but there has been no large scale universal solution. These urbanization efforts are definitely the most humane and socially acceptable solution to the villa problem, but they also generate a lot of backlash since there’s a lot of tax pesos involved and many tax payers do not feel like paying for a solution the squatters created themselves.

Villa Fraga in Chacarita was “urbanized” by the local city government, but there is still a small block left of illegal constructions. It is unclear why that was allowed to remain, instead of bulldozing it to the ground like the rest and offering payment plans to its occupants to reside in an urbanized building like the rest. With just that small block of illegal constructions intact in the screenshot above for the location of Federico’s phone, problems remain.

Many of these villa urbanization efforts were also done from the perspective of gaining a future voter base: Mauricio Macri’s PRO party has been the main proponent of integrating these shantytowns into the city instead of enforcing evictions. There is definitely something to say for this method: where would all these people go once evicted?

At the same time, none of these urbanization efforts have landed the PRO more votes: The rebranding campaign of Villa 31 to Barrio 31 was central to Horacio Rodríguez Larreta’s city administration from 2015 to 2023. His government built the city’s most modern school there, inaugurated a soccer field with stands, installed a bike-sharing station, and constructed two housing complexes.

However, the ruling party suffered a disastrous defeat in the 2019 primaries, after most of the urbanization efforts were completed. In Barrio 31, Larreta lost by almost 47 points to Matías Lammens, the Peronist candidate for mayor. In the previous primary election for mayor, in 2015, Larreta had lost by just four points.

There has been a push on social media lately to crack down on villas miseria in general, often combined with derogatory comments towards the occupants and their countries of origin.

It could be that this new migration police force modelled on ICE starts focusing most on the Villa Miseria areas when it comes to arrests leading to deportation.

Update on Argentina’s CBI?

So far, crickets.

Ever since Milei’s DNU on the creation of a national agency for Argentina’s Citizenship by Investment program in July, there have been no further updates on the requirements and application procedure.

The new rules around naturalization and obtaining citizenship have become harder for all immigrants, since Argentina now requires a two year stay without leaving the country before being able to apply for citizenship.

The timeline for citizenship hasn’t changed — since that would’ve required a change in the Constitution —, but the “no travel abroad” rule particularly hurt business people and higher income immigrants, since they will be more prone to make trips abroad more often. For lower income immigrants, this is unlikely to change much.

One potential delay for Argentina’s whole CBI initiative could be coming from Milei’s besties, the United States of America. This is just an assumption not based on any factual evidence, but now that the US is actively reviewing the reinstatement of ESTA waivers for Argentina, combined with the Bessent Put, it could be that the US views this as a potential security threat in the future and would prefer Milei held off on it.

I am in direct contact with the team working on the CBI with the Ministry of Economy, and as soon as the final regulation around the CBI requirements get published, they will be posted here.

Final Thoughts

For Milei’s new immigration police unit, the Villas Miseria could be one area of renewed focus. Technically, villa residents have committed a crime by illegally occupying public property, and could be deported under Milei’s decree published in May of this year.

However, it is more likely that this new unit will work in tandem with police, and proceeds with deportation only once an arrest is made for committing a crime.

Deportations of Villa Miseria residents would be a whole different ballgame, because many of the residents in these settlements have by now either obtained Argentine citizenship, or have children born in Argentina — which automatically grants the children citizenship, and parents cannot be separated from their children under Argentine law, nor can Argentine citizens be deported. A catch 22.

Therefore, it is unlikely we’ll see a full Bukele-style crackdown on barrios populares. There are too many problematic factors involved; residents’ family ties, the fact that the majority is blue collar working population, and disputes between local and federal jurisdictions intersecting in many of these villa locations.

The new migration department will probably have the biggest impact with regards to arresting and deporting foreign criminals — with or without official residency —, which is something that has never happened in the past. From that perspective it looks like Argentina’s lawlessness and “anything goes” might soon be over for immigrants who were looking to take advantage of it.

See you in the Jungle, anon!

Other ways to get in touch:

1x1 Consultations: book a 1x1 consultation for more information about obtaining residency, citizenship or investing in Argentina here.

March 2026 Event: The Wandering Investor Live Group Trip: Buenos Aires 2026. Get tickets here.

X/Twitter: definitely most active here, you can also find me on Instagram but I hardly use that account.

Podcasts: You can find previous appearances on podcasts etc here.

YouTube: Check out my channel for real estate info and more.

WiFi Agency: My other (paid) blog on how to start a digital agency from A to Z.

Does this mean immigration from the USA could be different?

"but now that the US is actively reviewing the reinstatement of ESTA waivers for Argentina, combined with the Bessent Put, it could be that the US views this as a potential security threat in the future and would prefer Milei held off on it."

Or what would the security threat be?